Until the 21st century, indigenous peoples were viewed as victims of the effects of climate change, not to mention colonialisation, rather than agents of environmental conservation.

This self-identifying collective of 370 million people is broadly defined by the United Nations as peoples who have inhabited lands prior to settlers of different origin arriving. They encompass groups defining themselves as “first nations or aboriginals and others, and those defined by outsiders according to their way of life and geography, such as hunter-gatherers, nomads, bushmen and hill people.

Evidence is mounting to suggest that the inclusion of indigenous people in environmental governance could be extremely beneficial, and enshrining their land rights in law could help protect ecosystems and carbon sequestration.

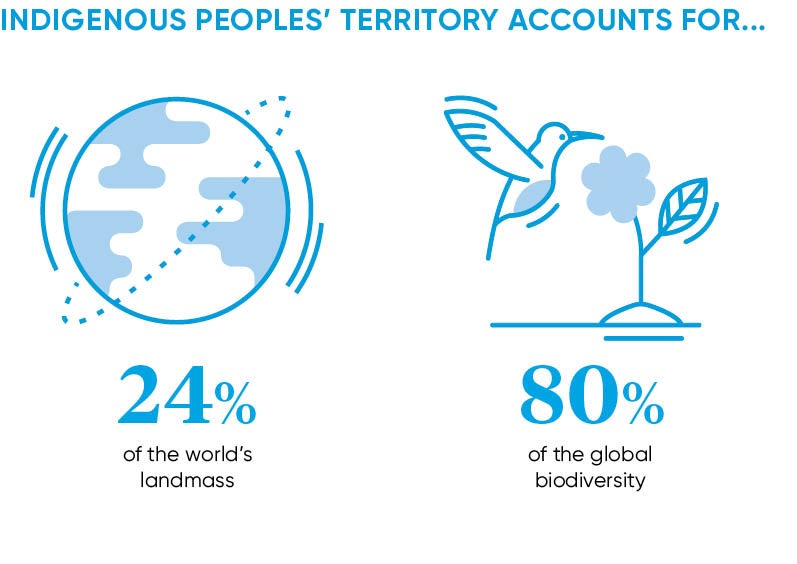

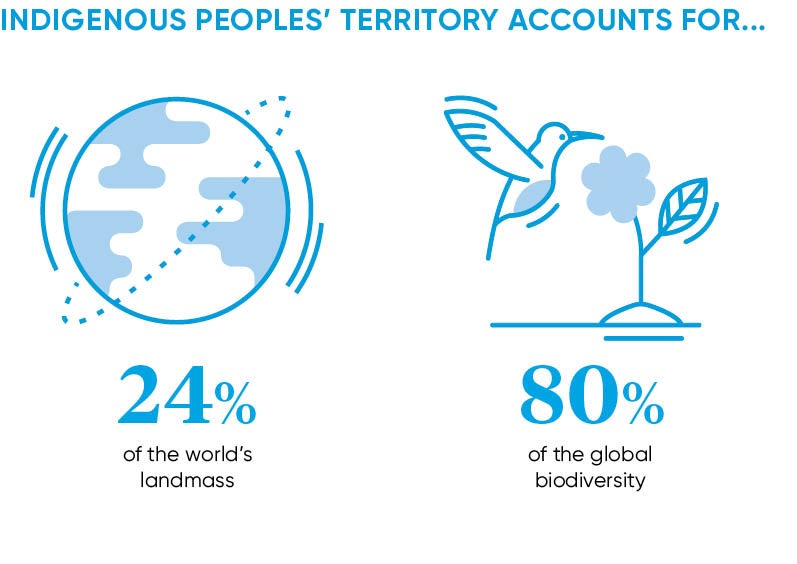

Indigenous peoples’ territories compose an estimated 24 per cent of the world’s land and account for 80 per cent of its biodiversity. For millennia, the majority of indigenous peoples have lived a sustainable way of life founded on a phenomenal knowledge of local ecosystems.

Indigenous people are becoming political actors in state-making, and reshaping legal principles and the legal basis of their relationship to the land

Indeed in 2016, the World Resources Institute (WRI) found that deforestation rates are two to three times lower in forested areas inhabited by local communities and indigenous people, and one tenth of the total tropical forest carbon is held by indigenous peoples and communities lacking formal land rights.

Increasingly, indigenous people are becoming political actors in state-making, and reshaping legal principles and the legal basis of their relationship to the land.

In Ecuador, Bolivia and New Zealand, indigenous activism has born a novel legal phenomenon, the notion that nature possesses rights. In 2008, Ecuador became the first nation to establish the rights of nature in its constitution. Just two years later in Bolivia, President Evo Morales, the first indigenous head of state in Latin America, rewrote Bolivia’s constitution to enshrine the law of Mother Earth or Pacha Mama, the Andean goddess said to sustain life on Earth.

Both nations legally codified the beliefs of the Quechua people, ten to eleven million of whom live in the Andes across Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Chile and Colombia. The Quechuan principle of sumak kawsay, a notion deeply embedded in Andean culture, which translates imperfectly into English as “good living”, teaches living in balance with nature.

This is a radical departure from conventional understandings of sovereignty and elevates nature in the eyes of law from merely property to being a rights-bearing entity, with all the attendant implications of protection and freedom from exploitation.

In practice, however, the demands of social development mean both Ecuador and Bolivia depend upon extractive industries; 14.8 and 12.6 per cent of their GDP respectively came from natural resources in 2014.

Bolivian President Evo Morales rewrote the country’s constitution to enshrine the law of Mother Earth or Pacha Mama

In Ecuador, the rights of nature are subject to principles of national development, legally all natural resources are the property of the state, and the state can decide to exploit them if deemed in the national interest.

New Zealand has taken a slightly different approach to rights of nature by awarding legal personhood to specific natural entities, such as land and rivers, which are sacred to particular native communities, who were instrumental in creating these new legal frameworks.

In 2014, the 821-square-mile Te Urewera Park, ancestral home to the Tuhoe tribe, became its own legal entity co-governed by the Tuhoe and the state, while more recently, in 2017, the Whanganui River Treaty passed into law, concluding an 80-year campaign by Maoris to protect the life-force and identity of the New Zealand’s third-largest river. New Zealand’s then-attorney general Chris Finlayson acknowledged the Maori thinking underlying the shift, saying: “In their world view, ‘I am the river and the river is me’.”

More often, governments fail to recognise indigenous peoples’ and communities’ customary rights to the lands they inhabit. When these rights are not recognised, lands can more easily be allocated to outside investors for development.

But as communities fight for the customary rights, the cost of dealing with land conflicts is rising for companies, says Peter Veit, director of the Land and Resources Rights Initiative at the WRI.

“Many companies I work with no longer believe that the lands being offered to them by some states are indeed vacant, idle and available for investment, and want to do their own due diligence, so WRI has developed tools like Landmark that offer first-order title searches,” says Mr Veit.

He adds that many companies would rather deal directly with communities if land registration documentation were available, while suggesting the time is coming for companies to do more to implement consistent company-wide policies on land issues in ways comparable to how labour issues are managed.

Many multinationals are striving to improve their environmental and social records, especially overseas.

“The quasi imperial approach to developing commercial opportunities is coming to an end,” says Rick Wheatley, director of the Vanguard Leadership programme at the environmental consultancy Xynteo, which helps companies apply their commercial capabilities to address countries’ development problems.

Across the developing world, governments, companies and NGOs are rightly engaged in the processes of modernisation and development. But in cases concerning indigenous peoples, they must recognise that protecting these peoples’ rights will mean protecting their right to choose not to develop.

Indigenous peoples should be allowed to choose themselves what degree of integration they have into the global economy and polity. If allowed to exercise these rights fully, they may even provide exemplary approaches to truly sustainable living.