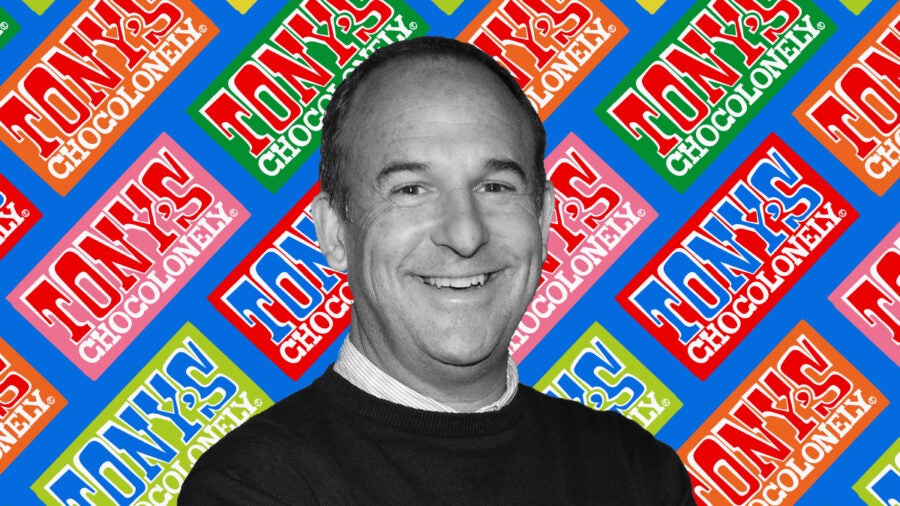

Douglas Lamont has found his lane. The CEO of confectioner Tony’s Chocolonely has a knack for picking mission-driven businesses that are thriving.

In 2022, after nearly 16 years as CEO of Innocent, the drinks brand, Lamont was looking for a change. As a champion of purpose-led businesses, he knew he wanted to go somewhere with an ethos similar to Innocent’s – but that wasn’t his only consideration.

“I was looking for an opportunity at a similar scale, in that scale-up phase from £100m to £400m in revenue,” Lamont says. For him, the mission is key, but it must work in tandem with profit and growth.

Moving from one B Corp-certified business to another certainly helped the transition. “You feel at home,” Lamont says. “The language that people inside the business speak is very similar and the mindset is there on how to deliver a successful company, but in a way that balances people and profit.”

Becoming a responsible-business figurehead

Bringing on a CEO who thinks in this way also makes it easier for employees to accept new leadership. “You’re there to take the company through a new phase,” says Lamont. “What you need at £100m is very different from what you need at £300m.” This growth phase can be uncomfortable for workers, especially ones who are passionate about the organisation’s vision and impact, and worry about compromising it.

“You have to demonstrate that you care deeply about the mission,” he continues, explaining that his previous work as chief executive at Innocent and chair of the Better Business Act, have helped to raise his public profile, making it easy for new colleagues to Google him and get a sense of his values. “Anyone thinking, ‘Who is this guy?’, could look me up and see things I’ve said publicly that resonate with them.”

If you want to change the world, you have to have a great product

This higher profile comes with challenges. Standing for something means your own actions, and those of the company you lead, come under greater scrutiny. “The great thing about being called ‘innocent’ is that it holds you to a pretty high bar,” says Lamont. “Initially, everyone was on our side when we were the challenger brand, but when you get big every journalist wants to find the guilty story – to write the other side.”

What matters, in such instances, is authenticity. “We have to be on our game every single day,” he says. “But if you believe in what you’re doing, it’s about doing your best against a set of standards. You have to make sure you’re never trying to pretend that you’re perfect.”

Progress, rather than perfection, is the goal. Indeed, as the company grows, decision-makers are liable to create as many problems as they solve, says Lamont, be that in terms of sustainable production or employee welfare. This makes understanding how to lead truly mission-driven businesses crucial.

Three steps to running a mission-driven company

For Lamont, there are three key elements to leading a mission-driven business and the first is getting your product or service right. “Whatever you’re selling, it has to be good,” he says. “If you want to change the world, you have to have a great product.”

Many business leaders who are set on running an ethical business fall down here, focusing too much on the mission and not enough on whether they are selling something customers actually want. “However focused you are on doing the right thing, if your core proposition is poor, people aren’t going to repeat-buy it,” he adds. “Mission can drive loyalty, but most people won’t buy for an ethical reason the first time around.”

This isn’t to say the mission isn’t important. Lamont’s second key to leading a responsible business is to decide on a clear, powerful goal and become seriously devoted to it. It’s not enough simply to highlight the mission in branding or to plaster it on the office walls. In Lamont’s view, to drive a mission successfully, business leaders may have to reconsider the role they play within the organisation.

“I’m the CEO of the mission, which is to end exploitation in cocoa,” he says. “I’m not the CEO of making Tony’s Chocolonely as big as it can be, no matter the cost. You have to get your head around that and you have to think differently. When it comes to your mission, you’ve got to really mean it. You’ve got to live it, not laminate it.”

And thinking in this way means sometimes acting in a way that seems counterintuitive in traditional business. In the case of Tony’s Chocolonely, this meant establishing Tony’s Open Chain, a collaboration platform where other industry players can buy Tony’s cocoa beans at cost price by signing up to the company’s sourcing model.

Sharing is caring: how Tony’s Open Chain works

For 15 years, the chocolate brand worked to develop an ethical sourcing model for its cocoa beans. This model was based on five sourcing principles, which include tracing the beans all the way through the supply chain, paying a fair price for them and establishing long-term partnerships with farmers.

In 2019, Lamont and his leadership team realised that, regardless of how fast Tony’s was growing, they wouldn’t be able to put a sufficiently high volume of beans through their sourcing model to make a real difference.

When it comes to your mission, you’ve got to live it, not laminate it

So they decided to open it up and offer the same beans that had been sourced through their model to any other company that wanted them – even if they were direct competitors. Now, you can find the Tony’s Open Chain stamp on all sorts of chocolate, from Waitrose’s Belgian chocolate line to Feastables in the US. “Is it good for my brand when I’m sitting on the same shelf as them but my products are more expensive? Probably not, but it is the thing that drives the most impact,” says Lamont.

Thinking beyond your own organisation

Tony’s Open Chain is emblematic of Lamont’s approach to business. “My urgency is to get people thinking about how you make change happen outside of just your company,” he says. “Because you being good on your own is not going to be enough.”

This is why he believes so doggedly in initiatives such as B Corp and the Better Business Act. Lamont sees the role of these as creating communities and a group of voices that policy-makers will need to take seriously. For him, the goal is that these groups will be consulted when the government wants to talk to business leaders, rather than the default simply being members of the FTSE 100. “What I want is for us to have a seat at the table,” he says.

Lamont believes that businesses such as Innocent and Tony’s Chocolonely, which demonstrate it is possible to be both profitable and responsible, can have a powerful impact on policy. “It gives lawmakers permission to raise the floor, because there’s less fear about unintended consequences,” he says.

The “floor” in this instance is about the standards businesses are held to. The Better Business Act, for example, calls for amendments to Section 172 of the Companies Act, which would call on businesses to report how they align people, planet and profit.

Lamont cites the example of P&O Ferries, which sacked 800 people in March 2022 and replaced them with cheaper agency workers. “When your default is profit maximising, and that’s the only lens that gets brought into the boardroom, then that’s the get-out-of-jail-free card,” he says.

Not just the right thing, the smart thing to do

Lamont hopes that, as movements such as B Corp continue to grow in the UK, so will the evidence that the traditional, shareholder-first view of business isn’t the only way to operate.

Although the tide seems to be turning, Lamont acknowledges that many larger enterprises still have their doubts. “It’s very easy for big companies to say, ‘That’s nice, but we’re a real company with real shareholders’,” he says. “But I’m not one that says being mission-driven is the preserve of small, cool companies. I’m only interested in change at scale.”

And it’s clearly working. Tony’s Chocolonely’s revenue increased by 23% last year to €150m (£125m), making it at least the 13th year in a row of revenue growth. At the same time, the Ivorian farmers who sell beans to Tony’s upped their cocoa income by 51%.

For Lamont, the way forward is very clear: “I’m an advocate for this stuff because I believe in it, but I’m also a capitalist. I believe in delivering good economic outcomes for shareholders, I just genuinely believe you can do both – and that’s what I fight for every day.”

Douglas Lamont has found his lane. The CEO of confectioner Tony’s Chocolonely has a knack for picking mission-driven businesses that are thriving.

In 2022, after nearly 16 years as CEO of Innocent, the drinks brand, Lamont was looking for a change. As a champion of purpose-led businesses, he knew he wanted to go somewhere with an ethos similar to Innocent’s – but that wasn’t his only consideration.

“I was looking for an opportunity at a similar scale, in that scale-up phase from £100m to £400m in revenue,” Lamont says. For him, the mission is key, but it must work in tandem with profit and growth.