Our notions of beauty are shaped by culture and weighed down by historical baggage. For too long, the beauty industry has sided with tradition and commercial expedience, serving up a narrow and restrictive vision of beauty that was youthful, feminine, Euro-centric and light skinned. But just as globalisation and digital forces have reshaped society, norms around beauty have also begun to shift.

Empowered by the internet, consumers, beauty influencers and independent brands are chipping away at the power grip once exclusively held by the glossy media, public relations industry and mainstream beauty brands. Together they are leading a revolution and setting diversity at its heart. The diversity agenda calls upon the industry to refocus business on consumers as people, to enable them to become the most beautiful versions of themselves, regardless of age, race, culture and gender.

There is an urgent commercial necessity for big brands to listen to consumers or lose ground to independents and internet-born beauty companies. “The beauty industry is becoming increasingly complex; our instinct is to dislike complexity, but we either embrace it or we’re not going to be around,” Camillo Pane, chief executive of French beauty conglomerate Coty, observed sagely at this year’s WWD Beauty Summit.

Marc Rey, president and chief executive of Shiseido Americas, also points out that sales growth of 42.7 per cent in the independent segment is far outstripping that of mainstream brands.

Part of the big brands’ problem has been complacency. The meteoric growth of the South Korean market over the past decade has put the beauty industry’s innovation shortfall in sharp perspective. The $13-billion market has pushed through innovations in product categories, products, textures and applicators. It has eaten the mainstream market’s share in East and South-East Asia because it has formulated products, among those that have broad appeal, specifically for Asian skin types and face shapes.

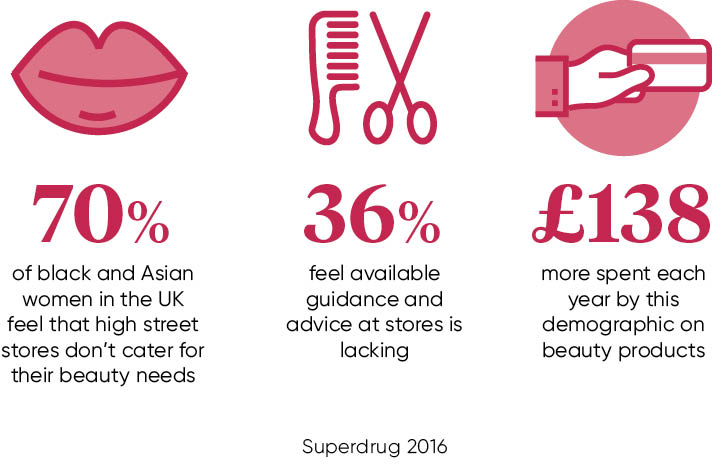

The mainstream beauty industry has failed to cater for dark skin tones

In the most fundamental of ways, the mainstream beauty industry has failed to cater for dark skin tones. There are notable exceptions of course – MAC and, most recently, L’Oréal with its True Match range – but in 2016 some 61 per cent of women in the UK were not able to find their foundation match. Women with darker skin tones often end up paying 70 per cent more for foundation from specialist ranges.

The opportunity is there and the demand is growing. When international superstar musician and Barbados-born businesswoman Rihanna released her Pro Filter Foundation line, which carries 40 tones, the darkest sold out fastest. Black women invest more than £4.8 billion on products and services each year worldwide, and spend twice as much as other consumers on skincare. By 2051, all of England and Wales will be as ethnically diverse as London is now, according to the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising.

The issue could be one of lack of awareness among the top guard. When Ghana-born London-raised Edward Enninful was appointed UK editor-in-chief of Vogue in April, he immediately recruited new personnel including black and mixed-race staff. Renowned make-up artist Pat McGrath joined as beauty editor-at-large and Vanessa Kingori as publishing director.

Just as black and Asian women have been ignored by the mainstream beauty industry, so too have older women. Finally brands have dropped marketing claims such as “anti-ageing” and “age defying” that imply ageing is a shameful and ugly process.

But there is still much to be done. Research by Mintel finds that older women feel frustrated by a lack of information and guidance on how to care for their skin as it ages. Brands have the opportunity to formulate make-up lines for older skin, and train their sales staff to show older women what techniques and products to use. Brands could also invest more research and development into products for women of colour who possess more melanin than Caucasian women and tend to age in different ways, experiencing pigmentation and skin sagging more acutely than fine lines and wrinkles.

A similar complacency has been shown towards the men’s market where choice is even more limited. It is no secret that men have long used traditionally female skincare products and there is a burgeoning market for cosmetics particularly among younger men. The male grooming industry, encompassing moisturisers, pomades, body hair removal products and blemish concealers, was worth close to $50 billion in 2016 and is expected to grow.

CoverGirl, a long-time proponent of diversity in the United States, made a statement with the release of their new mascara So Lashes, which featured its first CoverBoy, 19-year-old beauty blogger James Charles.

The same campaign also featured observant Muslim beauty blogger Nura Afia, 24, a Colorado native, who represents a powerful segment of the global beauty market in Muslim women. Women who wear the hijab are often serious beauty enthusiasts, favouring full make-up and dramatic looks. What is more, the global halal beauty market is rapidly growing and is expected be worth $52.02 billion by 2025, according to Grand View Research.

Multinational beauty brands must ensure that their messaging is broadly consistent across markets. It is too easy for localisation to appear more like moral relativism. Many of the top beauty brands selling skin-whitening products in Asian and African markets, where paler skin was traditionally associated with higher status, are catering to a lucrative though morally ambiguous market that is predicted to be worth £24 billion by 2024, according to Global Industry Analysts.

Nivea one of the leading multinationals selling skin-whitening products was founded in Hamburg in 1882 when Europeans also equated beauty with paleness. The brand’s very name derives from the Latin niveus meaning snow white. This year Nivea came under fire for a grossly misjudged White is Purity campaign that ran in the Middle East. Just as such a campaign would be considered unacceptable in Germany today, so too should it be unacceptable to consumers in Ghana, the Philippines, Ivory Coast and South Africa. Brands ought to be leading the diversity agenda, not trailing behind it.