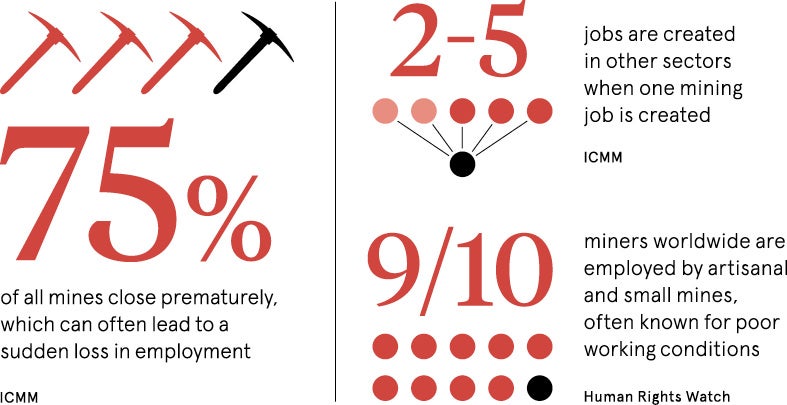

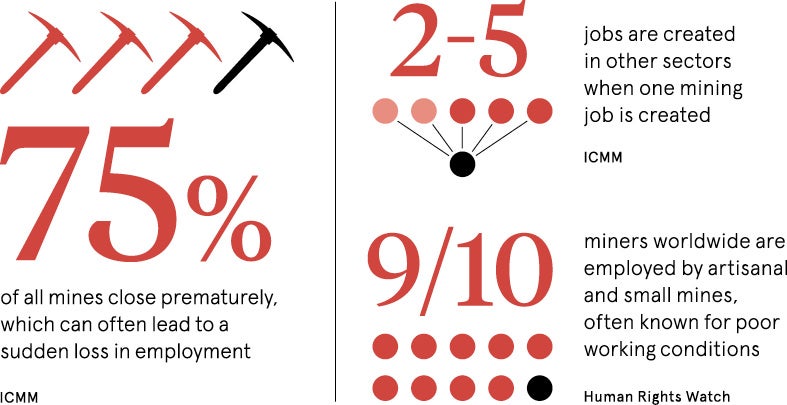

Even in the so-called digital age, the mining sector remains fundamental to almost every aspect of the economy. For every job created in mining, the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) estimates a further two to five are created in other sectors. And yet, even as mining technologies grow more sophisticated, the sector remains highly diversified and its problems highly complex.

Risk is endemic. With revenues buffeted by the stock market, reserves diminishing and new mines often taking decades to become operational, mining companies must also navigate complex political, environmental and social governance issues at every stage of the mine’s lifetime.

For all the challenges it poses, responsible mining is “a realistic goal”, according to the inaugural Responsible Mining Index (RMI). Launched in April, the RMI ranks 30 multinational mining companies against benchmarks in economic development, environmental responsibility, business conduct, working conditions, labour conditions, community wellbeing and lifecycle management.

Anglo American was the standout performer in 2017, owing to its investment in the economies of producing countries, its human rights due diligence and engagement with local communities, the RMI shows. Yet, the fact that almost two thirds of indexed companies performed well in at least one area, but poorly in others, demonstrates how difficult it is to balance the demands of responsible business.

Getting this balance right is crucial, especially in low-income countries where the multinational mining sector has the greatest potential to do good or harm. Low-income nations are disproportionately dependent on mining exports as a source of revenue; a dependence that has increased over the last two decades even as commodity prices have fallen, the ICMM’s Role of Mining in National Economies report says.

Good governance is the real determinant of the economic and social contributions of mining, such as the prevalence of corruption, and a country’s capacity to estimate returns from mining and negotiate mining taxes effectively. The majority of governments, some 66 countries out of the 81 assessed by the 2017 Natural Resource Governance Index (NRGI), inadequately govern their oil, gas and mining sectors. Fewer than 20 per cent were good or satisfactory.

Efforts to improve reporting have had an enormous impact on holding all stakeholders, whether mining companies, government officials or other contractor, to account. The hallmark Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative requires countries to file annual reports on mining data along the extractive industry value chain, from contracts and licences, production, and revenue collection and allocation, to social and economic spending.

Multinational mining companies, if they themselves are compliant and accountable, have an opportunity to encourage and build capacity in their host nations. “In countries or regions where government is weak or unable to provide basic services to its citizens, communities often look to mining companies to fill gaps with corporate social and infrastructure investment,” says Professor Neville Plint, director of the University of Queensland Sustainable Minerals Institute. Indeed, the mining sector impacts 11 out of 17 of the millennial sustainability goals, according to the United Nations Development Programme.

Many of the most successful case studies profiled by the ICMM are in fact partnerships between mining companies and host governments, and civil society, says Professor Plint. Mining companies have realised that communities living adjacent to operations typically bear the highest costs and see the fewest benefits from extractive enterprises, which accrue nationally and internationally. In Peru, for example, Glencore has worked to support the capacity of local communities through agricultural and business training.

Poverty does not have to be an insurmountable barrier to managing the mining sector sustainably. Burkina Faso was ranked highest among the low-income countries covered by the NRGI, with its mining sector ranked 20th overall. By the same measure, developed economies are by no means immune to a governance shortfall.

The NGRI notes that the trend towards silencing civic dissent in resource-rich countries is troubling. Daniel Kaufmann, NRGI president and chief executive, says: “Where freedoms of citizens and journalists are under attack, governance of the extractives sector is fundamentally impaired.”

Indeed, many of the systemic issues facing the mining sector are true irrespective of where a mine is located. The fallout from the sudden loss of employment to communities when a mine closes is one of the thorniest issues facing mining companies looking to improve their social and environmental impact, according to the ICMM, with 75 per cent of mines closing prematurely.

Often unlicensed and unregulated, working conditions in small mines are among the world’s worst

Companies further along the supply chain also have an important role to play in leading the demand for ethical supply, particularly if sourcing from intermediaries, which usually buy from artisanal and small mines (ASMs).

For all the headlines the top five multinational mining companies – Glencore, BHP, Rio Tinto, China Shenhua Energy and Vale – attract, the ASM sector employs more than 90 per cent of the world’s 40 million miners, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). Often unlicensed and unregulated, working conditions in small mines are among the world’s worst. Child labour persists in ASMs in Mali, Ghana, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, HRW says.

Public pressure from consumers and investors also drives change. Consumer-facing industries such as luxury jewellery were the first to inspire “ethical sourcing” initiatives in diamonds and gold. This year the Better Cobalt pilot launched with the support of Chinese mining company Huayou Cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where at least a fifth of the cobalt that is exported, and will end up in smartphones and electric vehicles, comes from ASMs.

In the near future, automation, sensors, robotics and bio-technologies will boost the mining sector’s efficiency and ability to measure performance. But its potential to do overall good will still hang on human decision-making. “We often underestimate our ability to make technological breakthroughs and overestimate our ability to make the social changes required to benefit from the new technologies,” Professor Plint concludes.