“Ethical” is applied liberally in today’s beauty industry, from vegan products to recyclable packaging, cruelty-free to sustainable sourcing. A sliding scale of what’s considered ethical, combined with a lack of regulation and clever so-called green-washing by some brands, has left many consumers confused and misled.

Sue Daun, executive creative director at global brand consultancy Interbrand, says the beauty industry can be one of the worst when it comes to truly ethical operations. “Big brands are talking the talk, but not consistently walking the walk,” she says.

Ms Daun accuses Yves Saint Laurent and Maybelline, owned by L’Oréal, as among the worst culprits, following claims to abolish the use of microbeads in all cosmetics, but apparently only eliminating them from exfoliants, washes and shower gels.

She says: “It is the brands that tout their ethical status, but don’t deliver that are the worst. Millennials are some of the most educated in the ethical space, and are highly critical and vocal when brands don’t deliver on what they promise.”

Mintel’s Natural, Organic and Ethical Toiletries report confirms just this, with more than 60 per cent of consumers saying they would stop using a brand if they found it to have “unethical practices”. But difficulty comes in defining these unethical practices. With almost three quarters of those questioned saying they found it hard to know how ethical a brand truly is.

Protecting the environment, recyclable packaging and animal welfare were all listed as top ethical issues by consumers, while 43 per cent of those surveyed said they would consider a brand’s ethical stance before buying for the first time.

Roshida Khanom, Mintel’s associate director for beauty and personal care, says consumers are becoming more and more sceptical about large, global corporations making “ethical” promises. She explains: “If a brand claims to stand for something, then they need to stay true to this. And in the age of social media, consumers are quick to call them out.”

Cosmetics giant NARS found this out the hard way. It faced a consumer backlash in the summer after revoking its cruelty-free status to enter the Chinese market. China demands animal testing on all imported cosmetics, which poses a big dilemma for brands looking to expand internationally.

NARS customers were quick to take to social media, calling for a boycott of the make-up giant that they claimed chased “profits over principles”. Ethical beauty advocate and influencer Kat Von D’s response at the time that NARS had “chosen a pay check over compassion” received almost 130,000 likes, ten times the number on NARS’ original post.

But what constitutes ethical for one consumer might be quite different for another. Data insights provider Hitwise has revealed that UK internet searches for “vegan beauty” soared 820 per cent from January to November this year. This surging demand is driven by both trends in the food industry and consumers considering a vegan brand is ethical.

But Jane Cunningham, editor of beauty website British Beauty Blogger, says we should be wary of this. “One brand may be vegan and that’s absolutely great; it doesn’t use animal products, but at the same time it’s absolutely full of chemicals. Consumers see vegan and assume it must be something good.”

Ms Khanom agrees: “There isn’t any regulation in the ethical beauty industry because the definition is so diverse, from how a product is made and where the ingredients are sourced to if the company has paid its taxes correctly. This all contributes to people not knowing if a brand is really ethical.”

The beauty industry has a voluntary certification process when it comes to ethical, natural or organic certified products

Unlike the food industry, which strictly polices the use of the word “organic”, the beauty industry has a voluntary certification process when it comes to ethical, natural or organic certified products.

Sarah Brown, founder of Pai Skincare, feels a lot of customers are being misled and duped. “Brand green-washing is a big issue. If consumers are paying a premium for a product, they need to know what they think they’re buying, they actually are,” she says.

It is the same for natural brands which is why Charles Beardsall, managing director for Dr Hauschka, feels that standardised certification is so important. “We are 100 per cent natural and a leading NATRUE certified brand, which requires you to be at least 70 per cent natural. Having the highest standards isn’t easy, but it’s up to all of us in the sector to ensure consumers are happy with what they’re purchasing,” he says.

According to The Good Shopping Guide, lack of proper regulation means a product can be called “natural” even if it contains as little as 1 per cent natural ingredients. “Big cosmetics firms love to use the word ‘natural’ on their products, but most skincare creams use synthetic chemicals, some of which are potentially toxic,” the guide says.

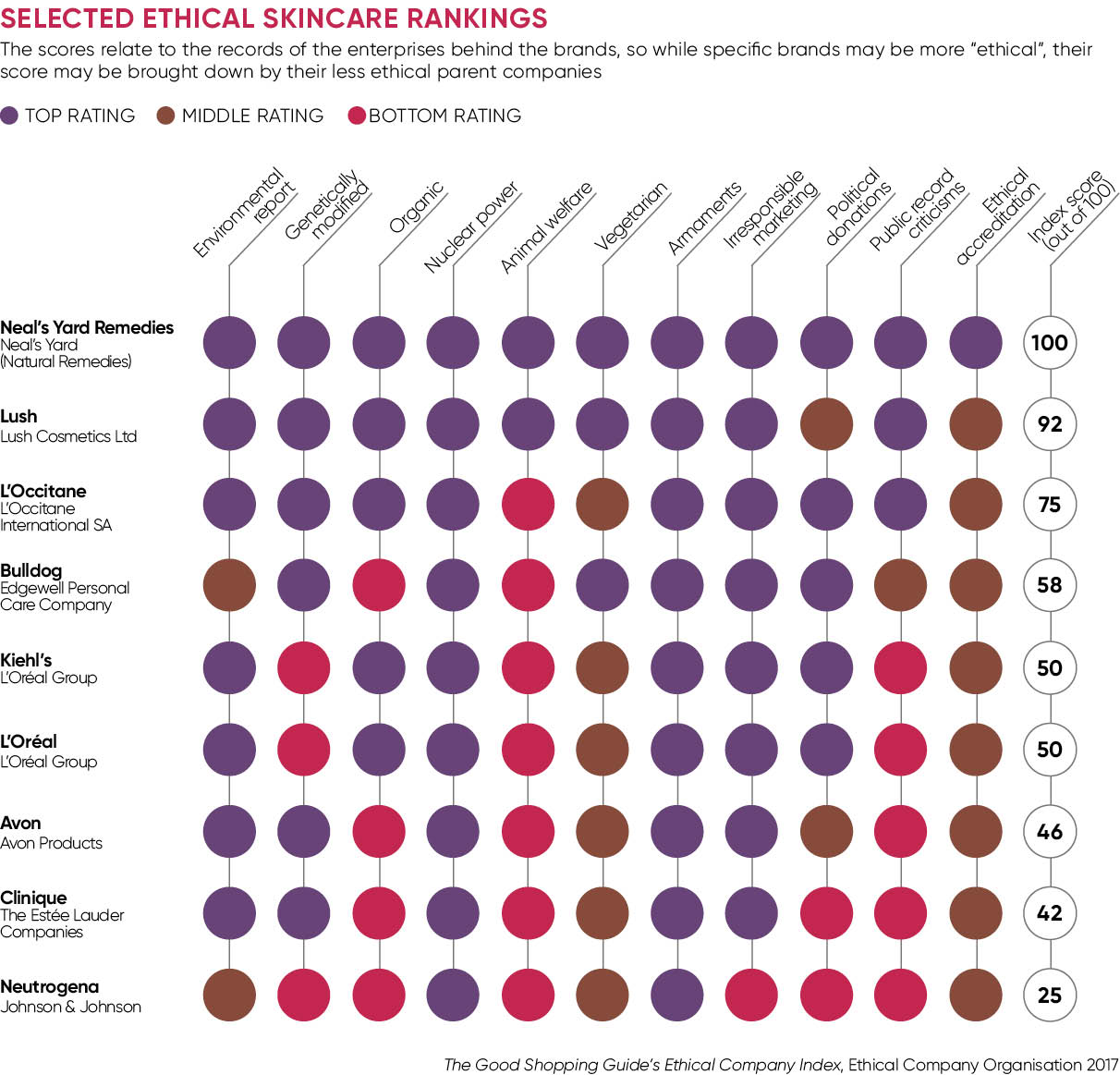

Kat Alexander, director of the Ethical Company Organisation, which publishes The Good Shopping Guide’s Ethical Company Index, says: “Our research relates to the records of the companies behind the brands. In some cases, apparently ethical brands score much lower than the public would expect because their ultimate holding company is involved in less ethical practices, often on behalf of other brands in their wider brand portfolios.”

Along with the issue of brands expanding into new international markets, such as China, the matter of brand equity is questioned when a seemingly “ethical” company is bought out by a not-so-ethical parent company. Men’s skincare brand Bulldog is a case in point.

Ms Alexander explains: “Bulldog did have Ethical Company Organisation accreditation, but this year has slipped down the rankings due to a brand buyout by Edgewell Personal Care. Bulldog has a cruelty-free international certification, but its new parent company tests on animals.”

In contrast, The Body Shop has moved up the rankings after it was sold to the more ethical parent company Natura Cosméticos S.A. With ethical beauty including such a broad spectrum of areas, offering consumers choice so they can make informed decisions is key, says Ms Alexander.

Brands such as Neal’s Yard and Green People scored 100 per cent on the Ethical Company Index. “Both brands are great examples of ethical companies which started out with a purpose to do things right. Their products are ethical – organic, natural, without animal-cruelty – and the companies behave in a responsible manner,” Ms Alexander explains.

With beauty giants such as Johnson & Johnson, Unilever, Estée Lauder Companies and the L’Oréal Group dwindling below 50 per cent on the index, it comes as no surprise that big household names have clubbed together to form a new initiative.

This new body, the Responsible Beauty Initiative, was launched in 2017 by Clarins, Coty, L’Oréal and Groupe Rocher to tackle the issue of ethics, supply chain transparency and sustainability. But is this going far enough?

Denise Leicester, founder of wellness and beauty brand ila Spa, says being ethical is about attention to detail at levels of the business. “When I started ila Spa, I wanted to be transparent; having an organic certificate was not enough,” she says.

“Our ethical bible goes to where we buy things from, whether we’re paying a fair price and what impact this is having on the lives of those in our supply chain. Ethical is not only the product, but how you treat your staff and the environment they work in.”