Corporates like a good cause. Not only do they want to offer good products or trusted services, but they also aspire to be forces of social change. Still, how companies prove they’re making a tangible difference is an increasingly difficult challenge.

After all, social impact measurement is no easy feat. For one, it’s costly. It also requires consistent and dedicated research that can last years. There’s also no universal set framework for all corporates to follow. And on top of everything else, concrete, tangible change isn’t always easy to quantify.

The push for greater accountability has become especially pertinent in light of public concern over climate change. The climate crisis is now part of daily conversation and political debate. It’s an issue big enough to push pupils to boycott school and protesters to shut down city streets on a weekly basis.

Businesses don’t always want to talk about what they want to do in case they get chastised because they’ve failed to follow through

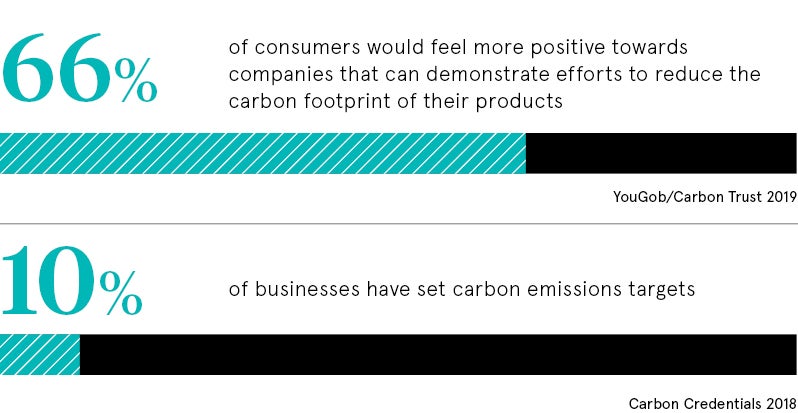

Now, if a company claims to have green credentials, consumers want evidence. A study released in April by the Carbon Trust found a majority (66 per cent) of consumers confirm they would feel more positive about companies that can prove they are making efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of their products. This would include introducing a recognisable carbon label on products.

And if a corporation fails to live up to its green public relations hype, it’s at risk of being accused of greenwashing.

This is far from a new concept. First coined in the 1980s in response to the oil industry’s PR blitz, greenwashing now applies across multiple industries, including fashion, beauty, food and technology. With consumers becoming more acutely aware of environmental issues, businesses cannot risk simply to turn the company logo green and dust off their hands.

Greenwashing: deceptive, and confusing

Ramifications of greenwashing vary. For the more blatant attempt to blur a business’s environmental harm, it led to big financial hits and long-term brand damage. But for the less egregious examples of greenwashing, it’s not always required brand control or triggered a dent to profit margins.

Clothing store H&M is vocal in efforts to push its environmental credentials. Indeed, the company has a Conscious clothing collection made using sustainable and recycled materials, and has led a major recycling initiative, collecting 1,000 tonnes of used clothes and offering discounts to those who donate their old clothes at its stores.

But even with its commitment to social impact, H&M has been criticised for diverting consumers attention away from its environmental harm through high-profile campaigns.

With its recycling project, critics claim even if 1,000 tonnes of clothing is recycled, this roughly equates to the same amount of clothes a brand of H&M’s size produces in a matter of days. So while the recycling initiative may be positive, critics say it’s insignificant in H&M’s wider, global operations.

In other instances, even the most supposedly green initiatives can be accused of greenwashing. The Rainforest Alliance certified green sticker, which is on products from coffee to bananas, is meant to convey a message of environmental and social responsibility. However, the on-the-ground reality has been found to contradict what the sticker suggests.

In 2014, Water and Sanitation Health, a US non-profit organisation, sued the Rainforest Alliance, citing unfair and deceptive marketing practices. It claimed the Rainforest Alliance certified Chiquita farms were marketed as sustainable. Instead, the lawsuit alleged the farms contaminated drinking water with fertilisers and fungicides, and air-dropped pesticides dangerously close to schools and homes.

Listening and learning in a fast-changing world

For some businesses, being “green” isn’t just a trend. Since its inception 40 years ago, The Body Shop has advocated social and environmental causes. The international beauty store has opened 3,000 branches in 69 countries while leading ethical campaigns focusing on where it can make a practical difference.

But even a company as green as The Body Shop still faces questioning over its environmental credentials. The store recognises the need to focus on how to adapt to a changing world. “Moving forward, we want to think differently on sustainability,” says Christopher Davis, international director of sustainability at The Body Shop. “Why? Because the planet and society are fast facing a crisis and we need to act now.”

One way The Body Shop is doing this is through science-based, social impact measurement guidance. The business’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts are guided by measurable and science-based goals from the Future Fit Business Benchmark, a framework with a forward-thinking approach that recommends practice according to the best available science.

“What we do is seek to be as transparent as possible and accept that while we are not perfect, we are always working to improve,” Mr Davis adds. “We want to make sure we are listening, learning and bringing new perspectives into the company.”

Social impact measurement can encourage accountability

So how can companies prove they’re actually doing what they say they are? While there is no one-size-fits-all practice, a number of frameworks, models and measurement tools are useful to help track and verify the impact of its projects and investments.

Some of the recognised standards include the Global Reporting Initiative, a standards organisation that helps businesses understand its impact on issues such as climate change, and the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, which offers benchmarks for sustainable business practices, and the World Benchmarking Alliance.

There’s also the B Corp certificate given to businesses that meet the highest standards of verified social and environmental performance and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which are increasingly being used as markers for effective social impact measurement.

Beyond this, there are some clear, evidence-based ways businesses measure environmental credentials. These include calculating carbon emissions, through the Carbon Disclosure Project, or the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Companies can also track their energy use, wastewater, pollutants and electronic waste across its operations.

In addition, effective social impact measurement means accounting for other factors that may have influenced the element being measured. Corporates need to ask themselves to what extent can a change be attributed to the activities of its business’s CSR efforts or investments.

Transparency is key

Of course, corporates can face heavy scrutiny over failed green projects and investments. The term “greenhush” is used for when corporates refrain from discussing green credentials to avoid being criticised for any failures. If a company fears the accusation of greenwash, then why would they shout about it?

Amanda Powell-Smith, chief executive of Forster Communications, is an expert in CSR working in the field for more than 20 years. She says while businesses may fear publicising goals in case they fail to meet them, transparency is better than doing nothing at all.

“Businesses don’t always want to talk about what they want to do in case they get chastised because they’ve failed to follow through,“ she says. “We should be encouraging corporates to say, ‘We have new targets, but we didn’t meet them because of these reasons and that’s why we’re going to be trying this new idea next’.”

While standards and benchmarks are not a foolproof way for a corporate to measure every level of its impact, they offer a constructive guide. Despite the challenges, corporates are working hard to measure their projects and investments, particularly with evidence-based methods.

Ms Powell-Smith says standards and benchmarks encourage corporates to work openly and honestly, and with accountability at the core of their aim. She says social impact measurement shows the possibilities of influencing social impact, not the limitations.

“Showing the progress and journey from the start is where impact measurement is really important,” she concludes. “It can show people what we can learn from and what’s possible to achieve.”

Greenwashing: deceptive, and confusing