On the face of it, John Deere might not look like the kind of organisation that is at the cutting edge of technology. After all, the American company is in the apparently earthy trade of making agricultural equipment.

Yet John Deere is taking a much more forward-thinking approach than some businesses when it comes to asset management. Its products, such as combine harvesters and tractors, come equipped with sensors that transmit mechanical data and enable it to inform farmers if a component is likely to fail, potentially around one month before the event.

It’s hoped that the so-called predictive framework analytics could save farms thousands of pounds by preventing unexpected periods of lost productivity. Anticipating problems with assets should ultimately reduce maintenance costs.

The benefits of such predictive maintenance of assets have been discussed for many years and the rise of the internet of things, with everyday devices connected to the internet, is expected to yield a revolution in how everything from transportation to buildings, power networks and factories are looked after.

Mark Taylor, technical innovation manager, IT, at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, says the rise of connected devices is already changing how assets are managed.

So, for example, owners of a haulage fleet will have much better information on the state of their lorries and should be able to spot issues at a much earlier stage, reducing downtime and saving money.

“The location, condition and maintenance requirements of assets can be tracked with real-time information. The benefits of this are huge, it will mean companies can identify operational risks in near real time and hopefully mitigate them,” says Mr Taylor.

Data could even inform future design improvements to prolong the lifetime of assets.

Adoption of a predictive approach to asset management in many areas has been slow

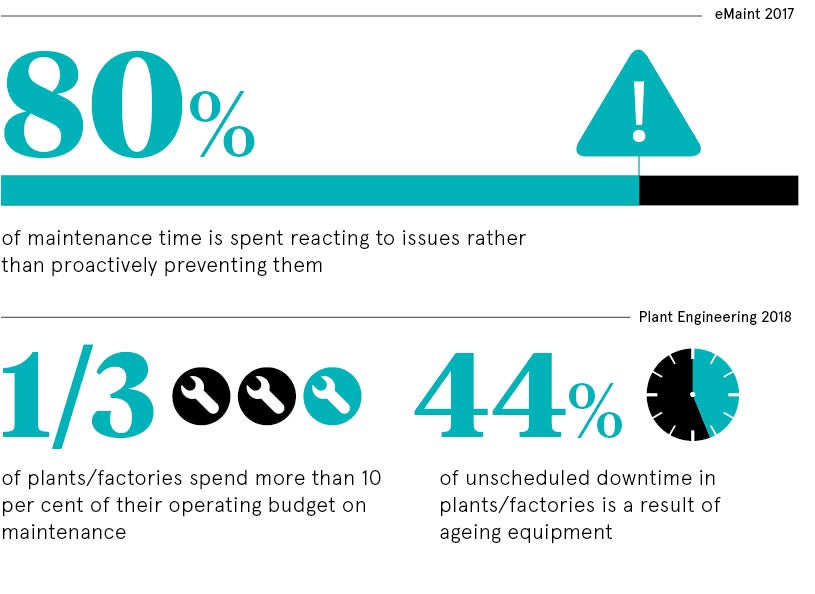

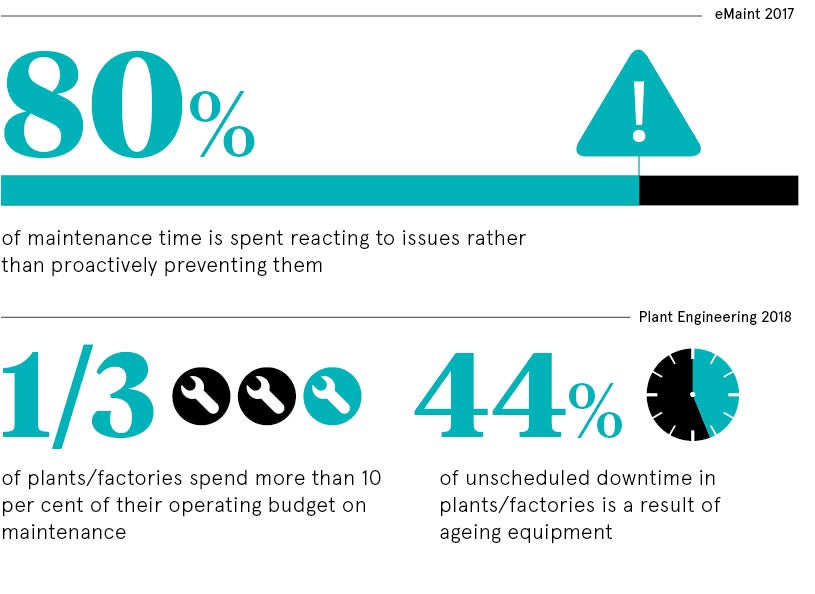

Yet adoption of such a predictive approach to asset management in many areas has been slow. That may be because of the lack of attention that even traditional asset management gets in some organisations.

Four out of every five asset owners do not have a complete understanding of what assets they possess, their condition or the required maintenance activities and budget, according to a global survey conducted by Arcadis, the engineering consultancy.

Bad asset management ultimately damages productivity, or output per hour. Poor maintenance strategies can reduce a manufacturing plant’s overall productive capacity between 5 and 20 per cent, according to Deloitte.

Richard Williams, UK head of asset services at CBRE, the property giant, says investment and management cycles can affect asset management. “A very buoyant market in recent years has meant that asset managers were spending more time buying and selling property, than actually actively asset managing each property,” he says. Now transactions are slowing down, assets are being more actively managed.

Another problem is that business plans and executive tenures can be shorter than asset lifespans. “Asset plans tend to be on a three-to-five-year cycle whereas a property’s life cycle and indeed leases are much longer than this,” says Mr Williams. “The asset plan often reflects short-term thinking, when a building is long term. We need to combine the short-term [planning] with a long-sighted approach.”

However, Julian Rose, founder of Asset Finance Policy, a regulatory affairs consultancy dedicated to serving the UK asset finance industry, says he is not convinced that industrial boardrooms are as ignorant of the importance of asset management as the Arcadis study suggests. “Consumers may struggle with some of the functions of their new washing machines, but businesses don’t have the luxury of not reading the instruction books,” he says.

That said, he concedes there is an issue when assets begin to reach the end of their lifetime. “Where businesses can struggle is with the disposal of assets, as they aren’t experts in valuing or selling equipment, or in clearing the confidential data that now sits on so many different machines,” says Mr Rose.

There are particular weaknesses in the UK when it comes to business investment, which has inevitable knock-on effects for asset management. Labour has been relatively cheap and flexible for many years, so it has been tempting to delay upgrading equipment, ultimately harming productivity.

Business investment was constrained during the financial crisis due to an inability to borrow. Access to finance is thought to be less of a problem now, but there has been a fundamental shift in UK companies’ demand for external finance. Over the last six years, they have become much more likely to want to grow under their own steam than seek financial backing.

If businesses are unwilling to borrow or sell equity to upgrade plant and machinery, they are probably less likely to invest in new ways of managing the assets they already have, which would require an overhaul to how they work.

Indeed, the structures of some industries are simply not set up for the new world of data-driven asset management. The transition could be painful. Take road and rail maintenance, for instance, where many jobs are reliant on routine manual checks. And installing sensors is one thing, understanding data is quite another. New recruitment strategies will be required to bring companies towards the new paradigm in asset management.

Malcolm Evans, director of the UK Manufacturing Accelerator, a specialised investor in early-stage manufacturing companies, agrees that the Arcadis survey was too gloomy, at least when it comes to industry. However, he concedes there is some catching up to do when it comes to what he calls “smart asset management”.

He concludes: “A degree of automation is very long standing in manufacturing – and it continues to become more joined up and shrewder in its analytics. But there is something of a time lag between the possible and mass adoption.”