When nuclear energy startup Transatomic Power, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology spin-out, announced it would be suspending operations, the company blamed its molten salt reactor technology for not scaling quickly enough. Despite this, the startup’s co-founder and chief executive Leslie Dewan wanted to support future nuclear reactor innovation and open sourced its intellectual property (IP), including patents both granted and pending for private and public research purposes.

Even with patents in place, companies still have to be mindful that the IP they’re sharing is not undermining their ability to compete

The energy sector has been “far more secretive and disinclined to engage in an ethos of sharing” than other sectors, says Colin Hulme, partner and IP specialist at Scottish law firm Burness Paull, which provides a range of services to exploration and production companies. However, given the rapid technological advances being made, he adds, the sector is under pressure to adapt and innovate to survive.

“To deliver the efficiencies that are necessary for survival, better planning is critical. Sharing IP and information can lead to the power to predict and insights that can turn unviable plays into cash returns,” says Mr Hulme.

Choosing to open source IP is about profit as much as progress

There is another reason why companies in the energy sector might want to open source IP, to build towards a greener and sustainable future. It’s for this exact reason that Tesla open sourced all its patents in 2014. Entrepreneur Elon Musk believed it would help grow the electric vehicle industry more rapidly and establish his Tesla brand as the market leader.

While most key players in the energy sector are unlikely to take Tesla’s total open book approach, says Mr Hulme, they are likely to take positive steps to increase collaboration and innovation, while being careful to maintain clear ownership of the IP.

On the face of it, sharing IP may sound altruistic and straightforward. In reality, it’s profit-driven and is no easy process. No matter their size and the industry they’re operating in, companies need to protect themselves so they can maintain a competitive advantage.

In what was described as an all-time high, the European Patent Office received nearly 166,000 patent applications in 2017. Closer to home, there were more than 22,000 patent applications in the UK in the same year and just over 6,300 were granted, according to analysis conducted by the UK’s Intellectual Property Office.

Sharing IP is not the opposite of patenting it

Without patents, companies run the risk of their technology being exploited. Applying for and then securing patents puts them in a stronger position when it eventually comes to sharing IP, says Peter Arrowsmith, patent attorney at one of the UK’s leading IP law firms Gill Jennings and Every.

“Sharing might seem like the antithesis of patenting IP, since the latter is about restricting the rights of other companies and making sure technology remains proprietary. But forward-thinking companies also need to consider how their technology can be more readily adopted,” says Mr Arrowsmith.

For Rockley Photonics, a company at the forefront of silicon photonics which manufactures chipsets for datacentres and sensors, sharing IP is critical for successful manufacturing. While the company has an intimate knowledge of photonics manufacturing, it doesn’t own any manufacturing facilities and instead contracts out the production, known as a fabless operation. This means the company has to share its IP in full with the partnering foundries.

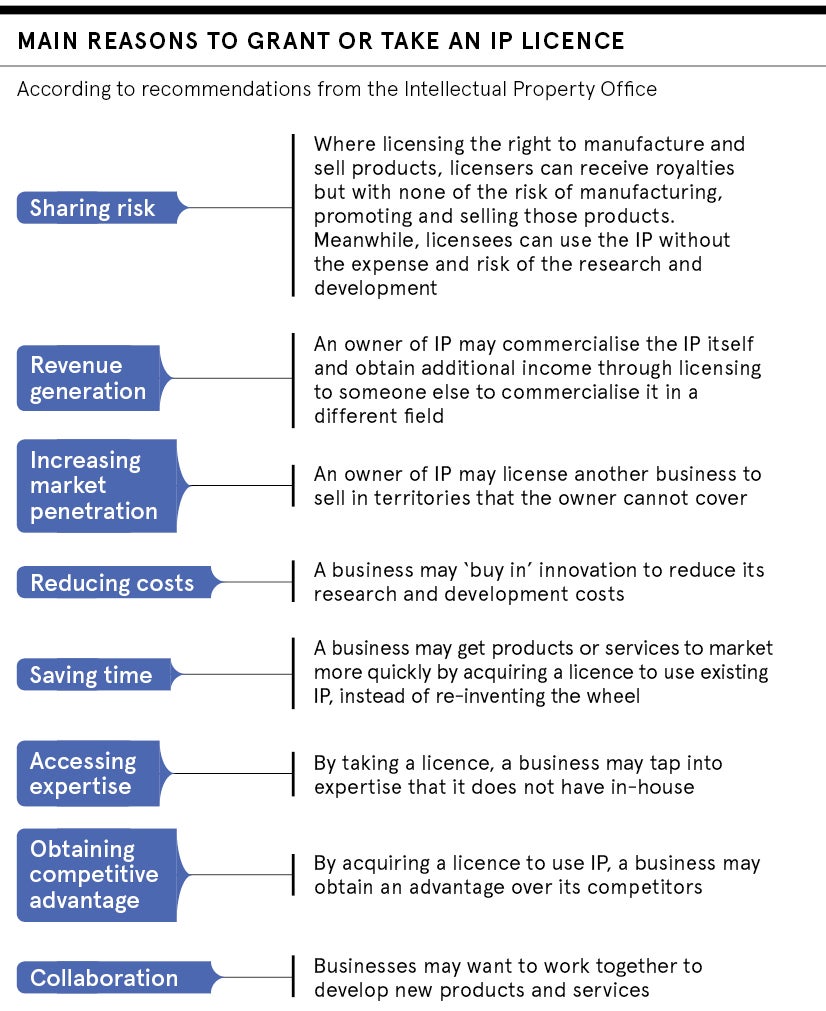

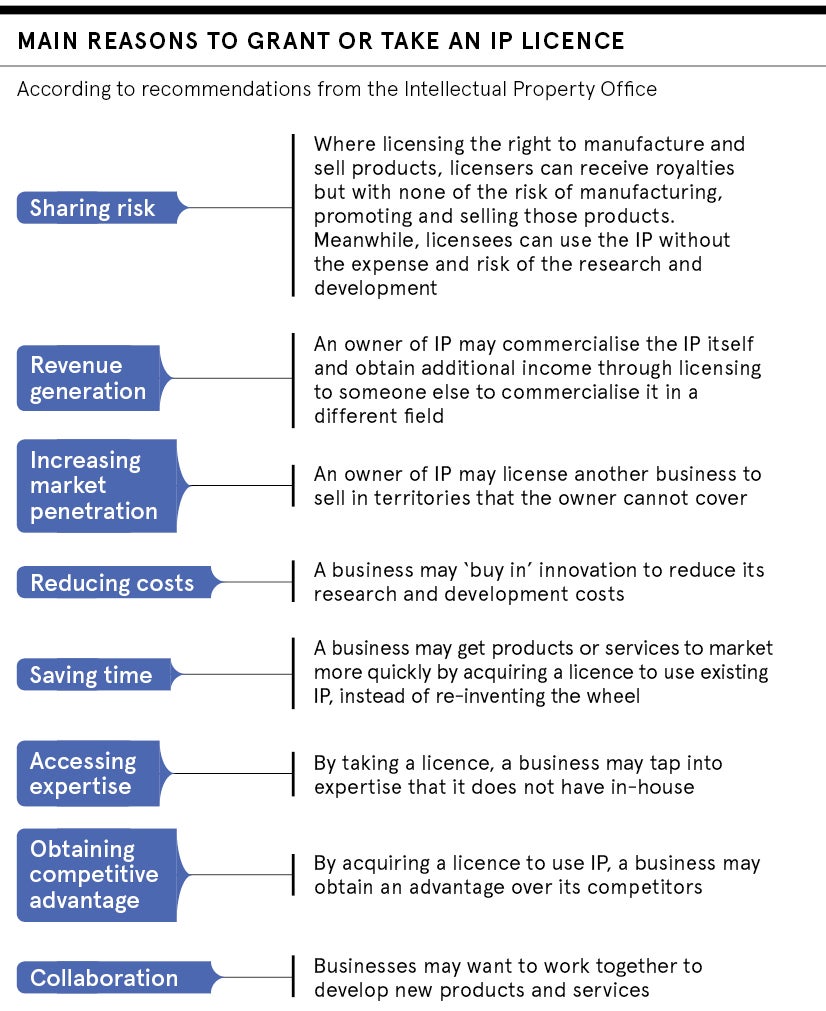

One of the more effective ways to drive innovation through collaboration is by licensing IP assets. “Startups, in particular, underestimate the value of licensing. It doesn’t get talked about enough,” says Merlie Calvert, a former lawyer and founder of Farillio, a legal technology platform which aims to simplify the law for entrepreneurs by providing them with all the legal documents and guidance they need to grow their business.

“Experts will tell you to protect your IP, and you should, but it’s only a step towards making real value out of creativity. When you license creative ideas, products and technology, you turn them into real assets, market testers and door-openers for bigger sales, orders and partnerships,” says Ms Calvert.

Licensing technology can help university departments make money

According to Mr Arrowsmith, licensing is how university technology transfer departments can effectively commercialise the innovations developed on campus. The university itself is not in a position to implement the technology in a consumer product, so they collaborate with a company and provide them with a licence, enabling the university to share some of the financial rewards.

“When it comes to medtech, academic research is treated much like big pharmaceutical discoveries. The difference is that drugs don’t need to be maintained, upgraded or compete in app store,” says Shuhan He, a doctor and founder of Boston-based startup Conduct Science, which commercialises high-quality equipment and digital tools made by scientists for scientists. “An infrastructure has to be in place to rapidly innovate and be able to upgrade for every smartphone model, iOS release or new programming language. This requires a successful tech transfer.”

The standard model of patenting and licensing can be a drawn-out process that involves lengthy negotiations and incurs high costs, which will often prevent academic discoveries from being commercialised, explains Mr He. His company aims to simplify the process. It offers to take on ideas and designs, and then pays the inventors and researchers royalties.

What to be wary of when sharing your IP

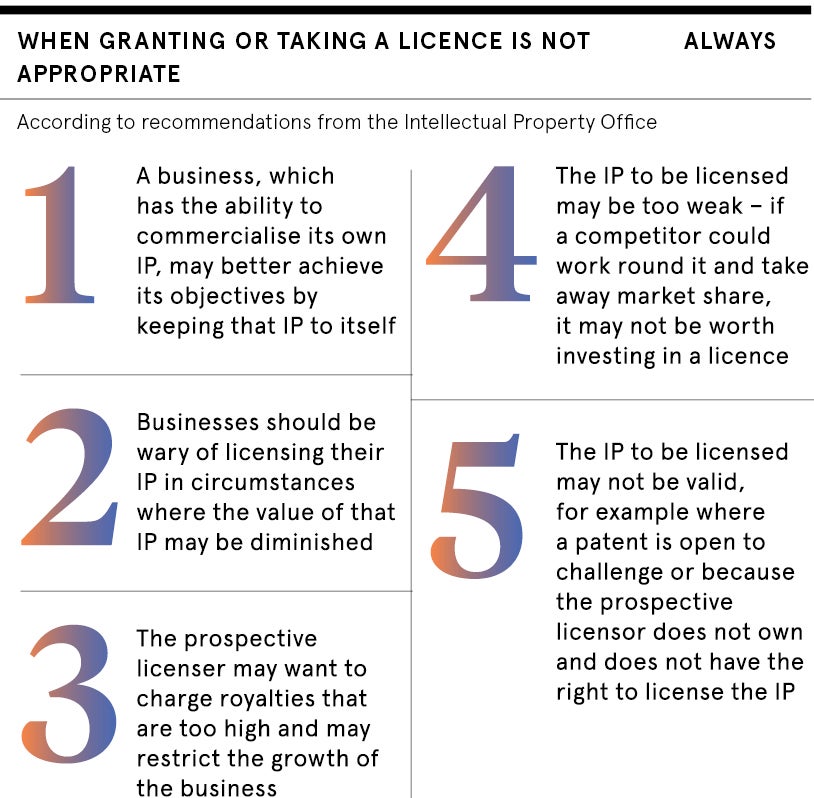

While inventors that don’t have the resources to secure patent rights can still benefit from sharing their IP, failing to acquire a patent can often affect the technology’s commercial viability and longevity; companies may be wary of disclosing technological developments in case third parties decide to take the invention for themselves. The World Intellectual Property Organization stresses that IP protection, especially patents, are crucial for acquiring technology through licensing.

Even with patents in place, companies still have to be mindful that the IP they’re sharing is not undermining their ability to compete.

“It’s impossible to have your cake and eat it,” says Helen Scott-Lawler, partner at Bristol-based IP law firm Burges Salmon. “Most companies will take care in what IP they share. They won’t give away unprotected crown jewels, or trade secrets, but they will share elements of their IP that don’t encapsulate all their market differentiators.”

Choosing to open source IP is about profit as much as progress