When the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, or AIA, came into force in September 2011, it was lauded by policymakers for harmonising US patent rules with those of the rest of the world. Nearly a decade on, many academics are doubtful about the net benefits and whether the rules are impacting organisations of all sizes to the same extent.

Professor Zorina Khan, a leading researcher on intellectual property (IP) at the National Bureau of Economic Research, says that in the knowledge economy, disruptive ideas often come from independent thinkers, but the AIA has meant the pendulum now swings more towards large established innovators.

Indeed, many smaller data-centric inventors protest that the AIA is stymying innovation. Rana Foroohar, author of Don’t be Evil: The Case Against Big Tech, says shifts in the IP system, regarding what can and can’t be patented, and a non-court adjudication system, which paves the way for rivals to invalidate IP, have left many wondering whether their IP is safe in the United States.

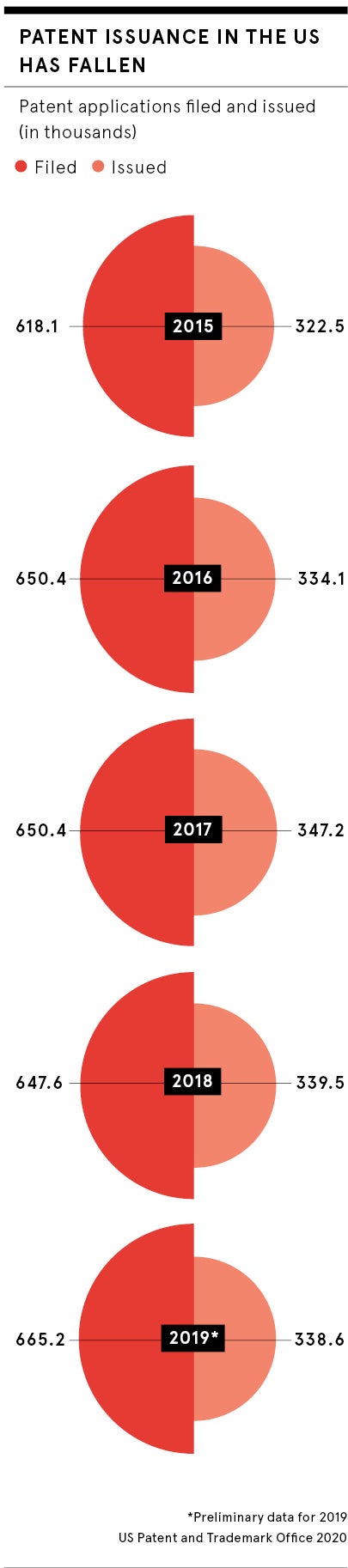

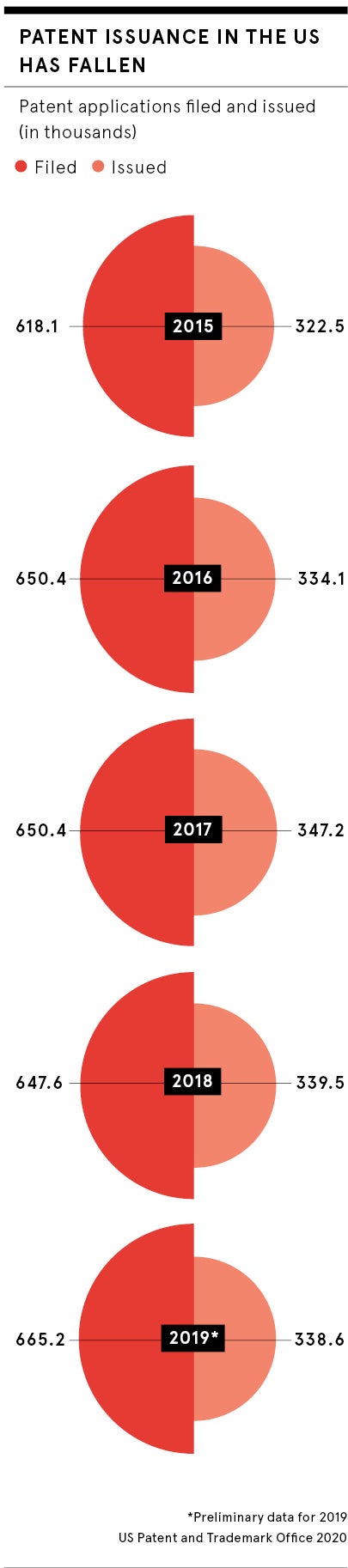

Some have already voted with their feet and left for Europe and China. Statistics from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), which reveal that since 2017 the number of patents issued in North America has been falling, confirms this trend.

How U.S patent law is hindering smaller innovators

But what are the changes that have allegedly shifted the needle in favour of large innovators? Khan points to three key AIA reforms which she says can penalise smaller players.

Firstly, in moving from a first-to-invent to first-inventor-to-file system, Khan believes the AIA takes the focus away from “the ideas of the first and true inventor” and “favours filers with the resources and personnel to quickly push through their applications”.

With the courts stifling innovation in diagnostics, in the long term the quality of life for many Americans could be adversely affected

She adds that evidence from Canada, which switched to first to file in 1989, backs up the claim that the AIA disadvantages independent inventors and smaller firms without their own specialised support for filing.

Khan also points out that under the terms of the AIA, any rival company can petition to revisit the validity of an issued patent. “This tends to undermine the strength of the property right in inventions,” she says.

Thirdly, Khan feels new litigation rules favour large filers. Patent owners were formerly allowed to file against multiple defendants in one single lawsuit, which was especially cost effective for small inventors. The AIA, she says, has made this more difficult and thus “disadvantaged smaller businesses that wish to prosecute multiple infringers or co-operate to defend against a dominant plaintiff”.

The overall reforms are complex, but Khan, author of a prize-winning book about patent systems, says the AIA has introduced substantial departures from fundamental democratic policies that have guided US patent rules over the past 200 years.

Why the AIA is not to blame

But not everyone agrees. Take David Kappos, for example. Widely recognised as one of the world’s leading thinkers on global IP, he was director of the USPTO from August 2009 until January 2013, and was an architect of the AIA and its implementation.

While Kappos believes that the future of innovation in America is under threat, he says: “It is important to differentiate between the AIA, which grants patents, and the highest courts’ interpretation of US case-law development, which takes them away.

“In terms of smaller innovators, the AIA has had an extremely beneficial effect. Its pro bono programme, for instance, has enabled thousands of under-resourced inventors to file their patents for free. Furthermore, it also facilitates fast-track patenting, which allows innovators to complete the patent process in just nine months, and was highly sought after by small innovators. So it is simply not correct to suggest that the AIA favours larger players.”

Instead, Kappos, who is a partner at New York law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore, says that a new rule, made up by the Supreme Court and unrelated to the AIA, is the issue. He says that the ruling, which is based upon the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Law of Eligibility for Patent Protection (Alice/Mayo Section 101 Law) “has undermined US patent system”. He believes that it has “created an environment where many inventions by software and medical diagnostics companies are now unpatentable”.

Kappos thinks that the only solution lies in overhauling Section 101, which he says has been “interpreted excessively narrowly” by the Supreme Court.

He explains: “The overhaul must consist of overturning the erroneous Supreme Court decisions, and also clarifying that 101 be interpreted broadly to avoid denying eligibility to important categories of next-

generation inventions.”

Kappos, who also lectures at Columbia and Cornell law schools, fears that if the courts abide by Section 101 in its current form, “innovators in the software and life sciences space, whatever their size, won’t invest new capital in new ideas”.

U.S patent law returning to the “middle ages”?

If the log-jam remains, he is concerned that continued failure to reform Section 101 will leave innovators scrambling for the only form of protection left, which is trade secrecy.

“This would be an extremely retrograde step as it would mean companies effectively returning to the middle ages regarding how they safeguard their IP,” says Kappos. “History has taught us that a culture of trade secrecy massively slows down the aggregate pace of innovation. We don’t wish to return to such a period.”

However, he believes that since the Supreme Court has so far not been persuaded to change course, the only other remedy will be to push reform of Section 101 through Congress. With the Supreme Court refusing to hear any high-profile patent case presented to it this term, Kappos considers Congress may be America’s last hope. Along with other industry heavyweights, he is working on legislative text, which he hopes will help Congress to change the direction of travel.

“It is vital that they do so,” he concludes. “The irony is that very few Americans know about Section 101 or the damage it is doing. But with the courts effectively stifling innovation in diagnostics, in the long term the quality of life for many Americans could be adversely affected. That’s the bigger picture and is why Congress needs to act and act quickly.”

How U.S patent law is hindering smaller innovators

Why the AIA is not to blame