The 21st century has so far proved a risk-strewn environment for big companies. Facebook’s crisis over misuse of user data can be added to the list of corporate disasters such as BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which almost ruined the company, and Volkswagen’s diesel emissions scandal.

The world’s biggest social network has struggled to overcome concerns about privacy, the spread of “fake news” and political manipulation, particularly since the revelation that Cambridge Analytica, a UK analytics company, may have improperly obtained the data of up to 87 million Facebook users. Facebook’s share price took a beating, some users deleted their accounts and regulators paid close attention, raising the prospect of new restrictions.

Facebook’s travails are larger in scale than most corporate crises, but the company is far from alone. The stream seems endless, whether it is the Harvey Weinstein scandal, exposing sexual abuse that went way beyond the entertainment industry, or credit-checking agency Equifax’s data breach, affecting more than 145 million people in the United States alone, or quality assurance disasters that have hit Japanese manufacturers such as Kobe Steel, Nissan and Takata.

Company chiefs seem confused by the range and complexity of business risks, unsure which are the most serious and what they can do to guard against them.

Business interruption and cyber incidents come top in Allianz’s latest annual survey of risks, while surveys by Aon and others have found the risk of reputational damage to be the main concern. Political risk, such as the danger of a US-China trade war threatening supply chains, has also jumped up the scale.

Yet Aon found in 2017 that risk preparedness was at its lowest level since 2007. “With the fast speed of change in a global economy and increasing connectivity, the impacts of certain risks, especially those uninsurable ones, are becoming more unpredictable and difficult to prepare for and mitigate,” it says.

Facebook’s problems combined an operational vulnerability – unauthorised use of customer data – with the explosive power of social media to amplify reputational damage

Facebook’s problems combined an operational vulnerability – unauthorised use of customer data – with the explosive power of social media to amplify reputational damage. “We use to talk about the ‘golden 24 hours’,” says Anthony Fitzsimmons, chairman of consultancy Reputability, referring to management’s window for trying to control a difficult situation. “Now it’s about the ‘golden 24 seconds’. It’s almost impossible to control it.”

The Facebook crisis is notable because it may have long-term repercussions that threaten its fundamental business model: selling personal data to advertisers, which allows them to micro-target their message to customers. If regulators restrict the way data can be harvested, Facebook may find it harder to make profits.

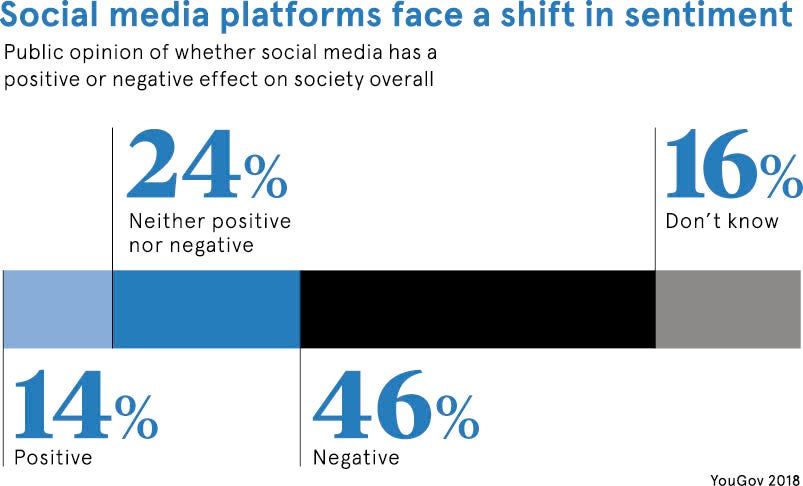

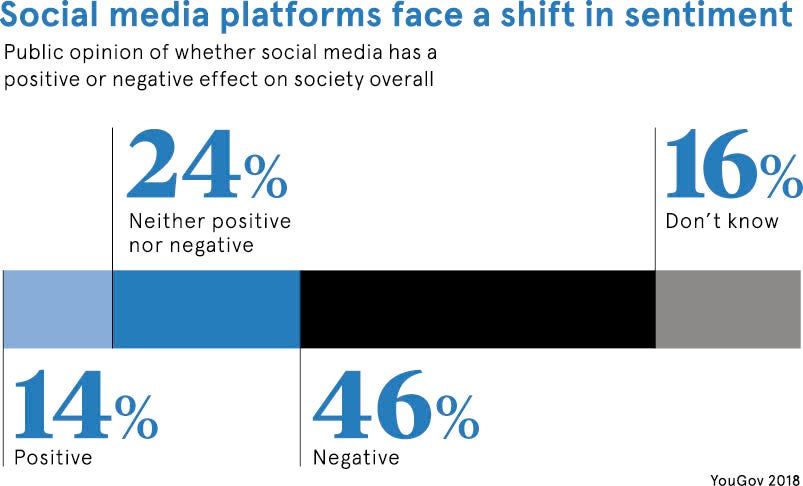

Has the company simply misread what its customers will tolerate and misunderstood its role in society? André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour at London’s Cass Business School, says Facebook’s social contract with users – “you give us your data, we give you online services you like for free” – seems to be weakening.

“Users are asking whether they want to give away data. Now Facebook will need to ask how much of its services it gives away for free. Alternatively it will need to ask what a new social contract with users might look like,” says Professor Spicer.

He adds that Facebook’s response was too slow. “It took a week to do the basics of crisis management: say what happened, acknowledge their role in it, say sorry, then tell us what they are going to do about it.”

Christopher Williams, reader in management at Durham University Business School and author of Venturing in International Firms, says the affair carries wider lessons for companies that collect user data and share it with other organisations. “The service attributes that companies develop and use to reassure users that ‘we will not exploit you or insult you’ are critical and determine winners from losers,” he says.

Dr Williams adds that Facebook “has an opportunity now to show that it has learnt from the episode and can take a true leadership position in the industry on issues around user trust”. That should include transparency and clear communication about how external organisations may access and analyse user data.

Companies can usually survive crises, but occasionally they prove fatal. The Enron scandal destroyed accountants Arthur Andersen, while construction and outsourcing company Carillion collapsed this year as a result of problems with public-private contracts.

Studies suggest the rate at which big companies are disappearing or losing their independence has speeded up, driven by deregulation, competition from emerging markets and technological change. The British Standards Institute, which has clients in 193 countries, says resilient companies are defined by strategic adaptability, agile leadership and robust governance.

Mr Fitzsimmons, co-author of Rethinking Reputational Risk, says: “Most crises are essentially system failures. Even if particular crises are hard to predict, the systemic weaknesses that cause them can be found and fixed before a crisis happens.”

In many cases, insiders are aware of a company’s weaknesses, but the message does not get through to leaders or warnings are not heeded. Sandy Parakilas, who was responsible at Facebook for compliance and data protection for apps from 2011 to 2012, claims he had warned the company that it was losing control of data to third-party developers.

Mr Fitzsimmons says companies should carry out crisis planning, including having “a leader who is trained and has the guts to go upfront if necessary”. They should also analyse where threats might arise, if necessary with outside help. One problem is that “when you talk to leaders, they readily accept that bad stuff might happen, but they think it only happens to other people”, he says.

Too often, leaders have fragile self-confidence, making them over-sensitive to internal criticism and reluctant to heed warnings. The best ones have “self-confidence sufficient to have room for humility”, Mr Fitzsimmons says, so they can take and welcome criticism.