Where are the female inventors? Despite the recent fashion for children’s books designed to redress the representation of historical female inventors, according to the Intellectual Property Office, women make up just 7 per cent of UK patent holders.

Though registrable intellectual property (IP) rights are typically held in the name of a company rather than an individual, explains Tania Clark, partner and trademark attorney at IP firm Withers & Rogers, “inventors are required to be named when filing a patent application and, in these instances, the majority are men”.

Megan Neale, co-founder and chief operating officer of SaaS platform LIMITLESS Technology Limited, tried to protect the company’s product, Crowd Service, a customer service platform. But the patent process isn’t cheap and she struggled initially.

“As a self-funded startup, you’re presented with a lot of tough decisions to make,” says Ms Neale. “We were told that to patent the product just in the UK would cost at least £50,000. Our vision has always been for Crowd Service to be used globally, but to cover all countries this would cost a minimum of £150,000.”

So the team built the software code and product as fast as possible and protected the IP as they went. “Within six months from concept creation, we were live with our first client Unilever plc,” says Ms Neale. “Unilever also decided to invest in LIMITLESS through its Unilever Ventures business.”

Perhaps women just take fewer risks. “When designing a new product and you’re not sure you want to go down the IP route, you need ask yourself whether your product is truly valuable enough to warrant a patent. If the patent isn’t granted, how much money will you have wasted? You need to be comfortable with the risks,” she says.

It could come down to semantics. Ms Neale says: “I’ve been called a creative and a solutioner, but never an inventor. I started inventing software solutions in the 1990s, but didn’t realise it until recently.”

Things are changing, says Penny Gilbert, partner at law firm Powell Gilbert. “While patent law might previously have referenced the ‘man skilled in the art’, it is now the ‘person skilled in the art’ that is enshrined in statute,” she points out. In fact, there are no actual barriers to women filing patent applications and obtaining patents, Dr Gilbert says, “other than their educational and career choices, and the stereotypes around these”.

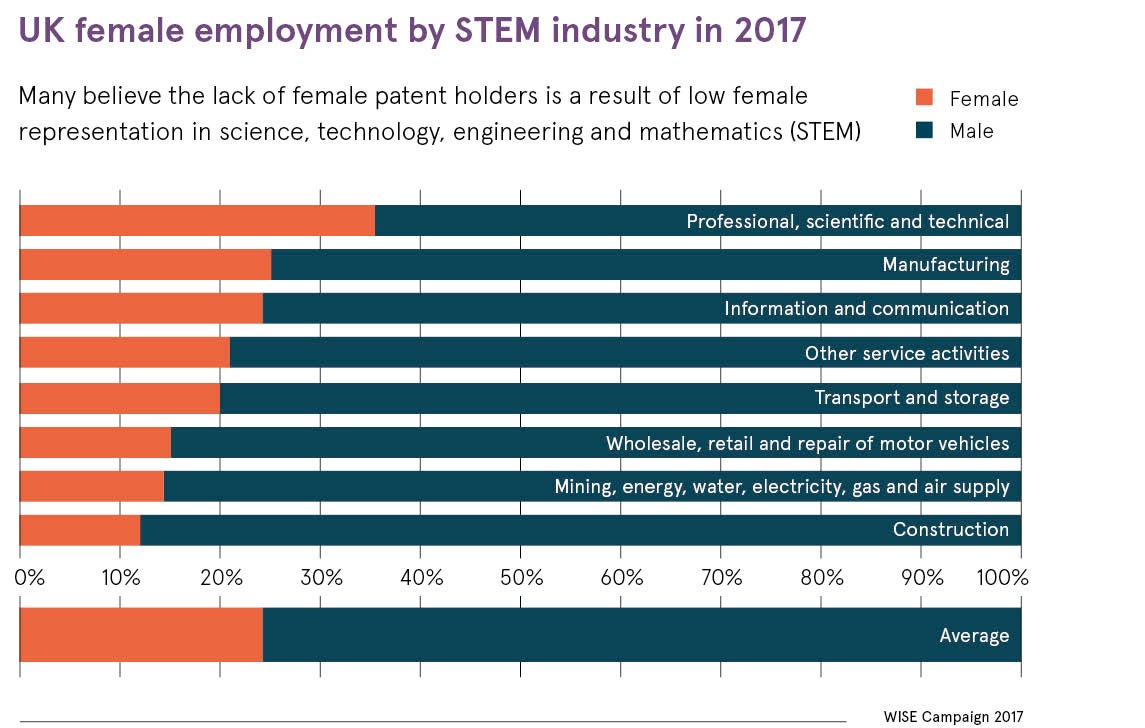

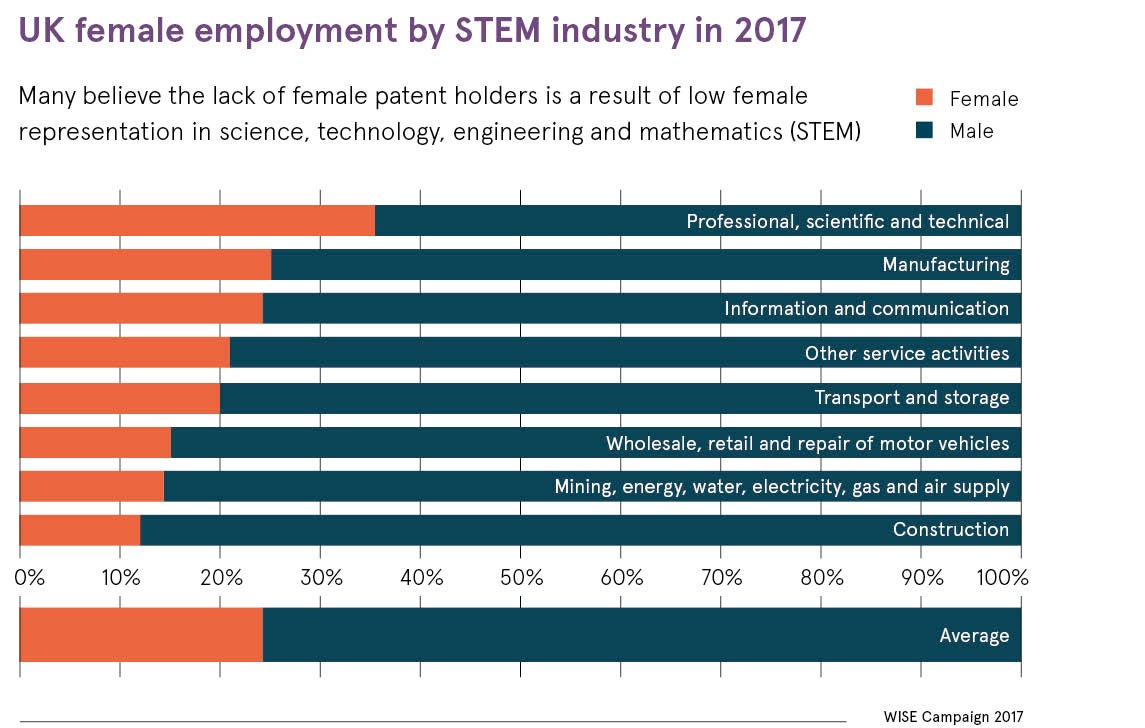

Emma Graham, partner and European patent attorney at IP specialist law firm Mewburn Ellis, says: “The under-representation of women holding patents is not due to IP law itself. It is due to the lack of women doing the ‘inventing’. Women are under-represented in science and engineering, and particularly in roles focused on the inventing process, such as design engineering or product development. It’s predominantly individuals in these roles who become patent holders.”

However, interestingly, women are participating actively in IP law, says Dr Graham. According to the Intellectual Property Regulation Board, the proportion of female IP attorneys (28.5 per cent) is markedly higher than that of female patent holders.

Ruth Wright, senior associate at Gill Jennings & Every, has an interesting hypothesis: “The biggest patent-filing numbers are in fields such as telecoms and consumer electronics, where the inventors have degrees in subjects like engineering and physics, as opposed to life sciences where women are somewhat better represented. While patents certainly get filed in life sciences, many years of work can often lead to a single, crucial patent on a particular drug formulation.

“In contrast, in telecoms, thousands of patents go into each new telecommunications standard and, in consumer electronics, a new model of smartphone is developed every year and can have hundreds of patents associated with it. I’m willing to bet this disparity skews the overall numbers.”

Ms Wright also believes that many patent filers don’t understand the correct way to name inventors on patent applications. “That’s a big problem – a US patent can be invalidated if the right inventors haven’t been named,” she says. “Inventor lists get compiled in the same breath as author lists for technical publications, especially in universities. This often means crediting in order of seniority, when in fact the crucial thing is who came up with the inventive concept.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if this, coupled with the cross-industry problem of women not progressing to senior roles, has an impact on the number of women named as inventors.

“You have to be ballsy to get yourself named as an inventor, putting forward a case why your contribution is important. Women are often not good at that and suffer from ‘imposter syndrome’.”