Since the global financial crash, public companies have faced what must feel like a barrage of new reporting requirements. Regulators have pushed for greater corporate transparency in the wake of the 2008 economic carnage in an attempt to regain trust and rebuild reputations.

But during the ensuing decade, new global media channels grew, evolved and spread, which enlarged the public’s access to information and the speed at which they receive it, refocusing the spotlight on corporate actions.

How you are viewed in all manner of different aspects, not just products and services, but your impact on society as an employer is right at the top of the agenda now

Reputational risk has traditionally been seen as an outcome of other risks and not necessarily a standalone risk. This view has been gradually changing because it is increasingly clear that reputation is critical to the viability of a company.

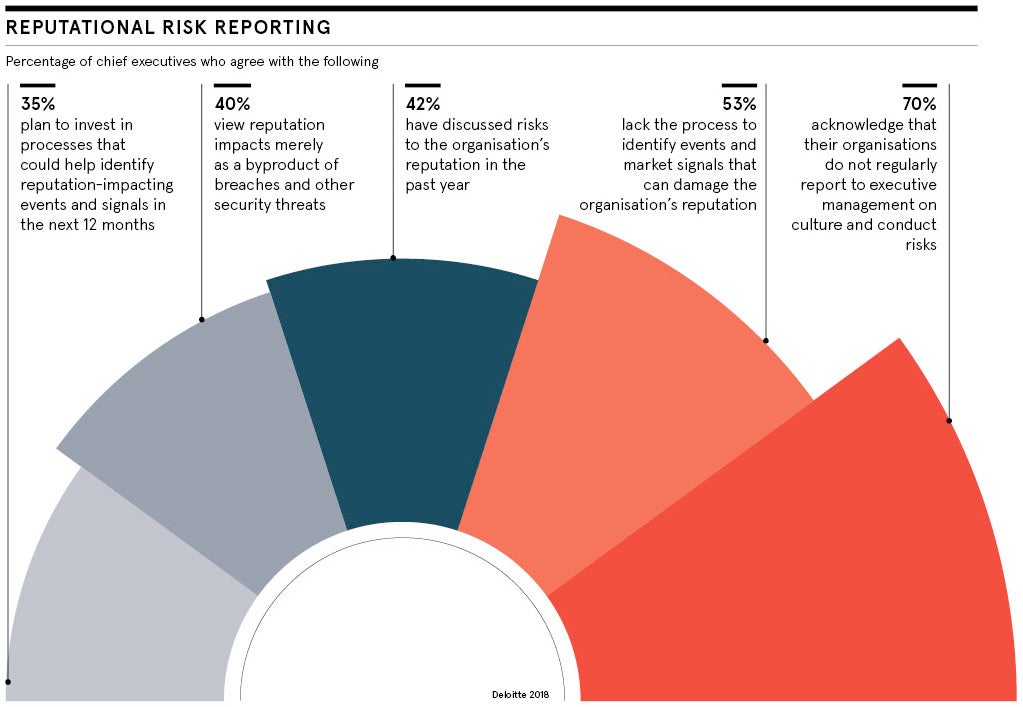

Management not doing enough to protect from reputational risk

With this greater knowledge and means of communicating, societal norms and public expectations of companies have evolved too. People’s voices are louder and opinions, valid or otherwise, can spread around the world in nanoseconds. Nevertheless, trust in companies has recovered somewhat, according to the Edelman 2019 Trust Barometer.

With this greater knowledge and means of communicating, societal norms and public expectations of companies have evolved too. People’s voices are louder and opinions, valid or otherwise, can spread around the world in nanoseconds. Nevertheless, trust in companies has recovered somewhat, according to the Edelman 2019 Trust Barometer.

Trust has rallied so much so that 76 per cent of those surveyed by Edelman say chief executives should take the lead on change rather than waiting for governments to impose it. This suggests that despite the consistent demands for greater corporate disclosure, management are still not leading on change as quickly as the public want, and therefore still haven’t understood how quickly reputation can be affected in a high-speed world of global communications.

“Traditionally, risk officers have seen reputational risk as a consequence of other things happening. Is it a risk of risks or a risk in its own right?” asks Mark Hutcheon, director of risk advisory at Deloitte.

Mr Hutcheon says if that question had been asked five years ago, no one would have seen reputational risk as a standalone risk.

Companies must get better at managing intangible assets

Another core reason why reputational risk is more vital is because the balance between tangible and intangible assets has tipped towards intangible value, such as trust, reputation and goodwill, elements that are not as easy to manage as physical machinery. Therefore, the valuation of a business can be increasingly found in its intangible assets.

“Companies are good at managing humans and physical assets, but they aren’t good at managing intangible assets. We haven’t got our heads around the idea that we have a whole new class of assets. We have to learn how to manage them, understand the risk and put strategies in place,” says John Ludlow, chief executive of risk managers Airmic.

This shift, coupled with the rapid rise in social media usage, has made reputational risk much trickier to handle and therefore more important to manage. Suddenly, the incidents that can damage reputation are a lot more volatile, quicker acting and, in some cases, can become systemic risks to organisations.

Uber’s decision not to report to police sexual attacks and other crimes by its drivers for fear of damaging its reputation massively backfired for the taxi-hailing giant when in September 2017 Transport for London revoked its licence. Uber claims to have turned over a new leaf by bringing in chief executive in Dara Khosrowshahi. Its reputation, however, remains tarnished in one of the most important markets for Uber outside America.

Greater collaboration needed between risk managers and communications

Companies that try to hide wrongdoing, such as German car manufacturer Volkswagen when its emissions scandal was uncovered in September 2015, are suffering for longer and deeper because news travels fast and you can’t fix a brand like you can fix a misfiring machine.

“How you are viewed in all manner of different aspects, not just products and services, but your impact on society as an employer is right at the top of the agenda now. This is a new phenomenon in its importance,” says Jon Terry, diversity and inclusion consulting leader at PwC UK.

Although it’s high on the board’s agenda, change seems to be slow. Traditional company structures aren’t designed to manage the new risks to reputation, says Mr Hutcheon. They need to restructure their thinking and teams to build early-warning systems that detect reputational risk.

“Companies are getting there, but it’s just not joined up enough yet,” says Airmic’s Mr Ludlow.

Traditionally, risk is dealt with by risk experts, while reputation tends to be managed by the corporate affairs or communications teams. When those two teams work in silos, lacking any meaningful collaboration, risks can rise up undetected.

“That’s where it falls down,” Mr Hutcheon says, “when the gap widens between the comms team, who are the antennae for the business, and the professional risk experts. That’s when companies face real risk exposure.”

Diverse companies avoid reputational risk and reap rewards

Some evidence of this can be seen by the fact that with one week to the deadline of April 4, fewer than 4,000 of the 10,000 large UK companies required to report on their gender pay gap had still not disclosed the average difference between men and women’s pay per hour. Increasingly, the gender pay gap is a focus not just for female employees, but for investors and other stakeholders too.

In contrast, FTSE 100 drinks giant Diageo, which has seen its share price rise exponentially over the past decade, is repeatedly held up as a company to be admired because of its progressive policies, such as its latest one on full pay for parental leave for the first 26 weeks for all its 4,500 employees.

“It’s a new era for business. Large businesses enjoy much less control and ultimately that’s an empowering thing. A lot of control is moving out of the business to society. And that will align how business puts back things into society when they are constantly under scrutiny. It’s going to feel hard for businesses, but that’s the way things are going,” Mr Hutcheon says.

Research consistently shows that more diverse companies are more profitable and current thinking suggests more open and transparent companies reap the rewards. As counterintuitive, and perhaps as painful, as it may be to meet the public’s new demands, management need to disclose more, more frequently.

Understanding and managing reputational risk is all part of societal change. Aligning commercial interests with social ones shouldn’t be such a hard place to start. More importantly, it’s not a question of unlimited disclosure, but relevant disclosure. Whether we’ve reached a tipping point in disclosure terms will be determined perhaps by how corporates handle the next financial crisis.

Management not doing enough to protect from reputational risk