Ex-Army engineer Doug Johnson-Poensgen worked at BT and Barclays Bank before he took a leap of faith. Inspired by a desire to use technology to solve what he calls “real world problems”, he set up Circulor. The London-based company, of which he is chief executive, uses blockchain and artificial intelligence to track global supply chains, ensuring products are traceable from source to end-user.

Brexit is causing many corporations to reassess their strategies and supply chains, irrespective of political persuasion

“It’s hard to know exactly where the cobalt that’s mined in the Congo goes before it ends up in your car or the palm oil that’s in your ice cream,” says Mr Johnson-Poensgen. “And there’s never been more pressure for companies to provide that transparency.”

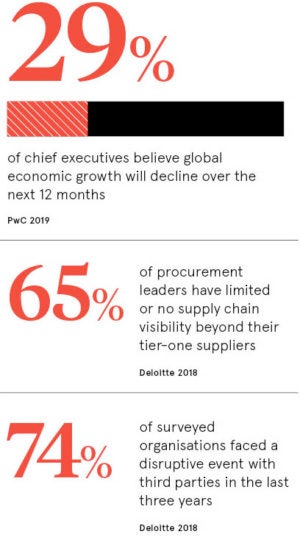

With a multitude of risks facing almost all major supply chains, from geopolitics to natural disasters and financial pressures, he says Circulor, established in 2017, is “making it harder to game the system”.

Customers increasingly demanding greater supply chain transparency

Customer scrutiny of the practices of large corporations is increasing at a rapid clip. More than ever, there’s pressure on retailers to reassure buyers that the tantalum used in their smartphones and laptops is not mined in war zones and sold to perpetuate conflict and bloodshed.

“Relying on self-certification is just no longer good enough,” says Mr Johnson-Poensgen. “We need to do more.”

Circulor has five large clients and several more in the pipeline, according to the chief executive. Demand for its services highlights the vast challenge of trust and accountability faced by corporations in a world where consumption is fuelling production at any cost.

But more generally, it underscores that businesses are being forced to be much more cognisant of their environment in an increasingly interconnected, yet deeply unpredictable, world.

How US-China trade wars are threatening global business

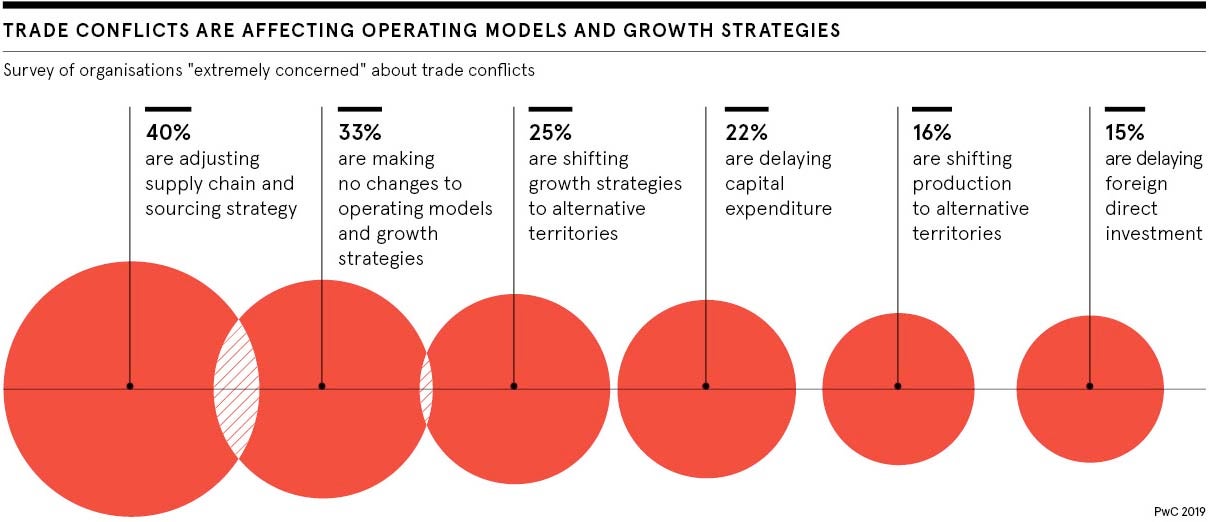

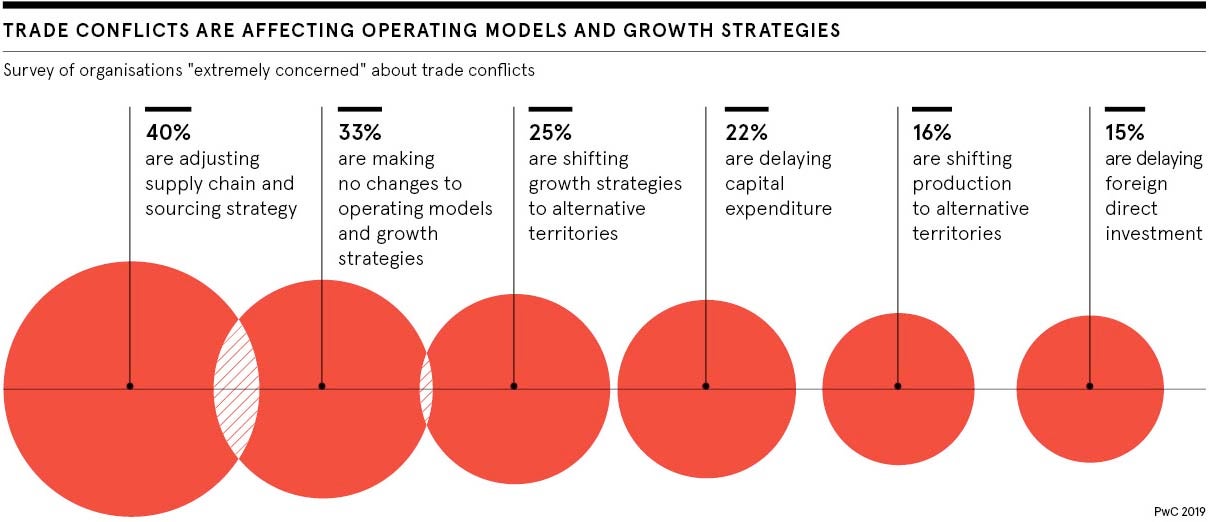

The risks are omnipresent. Simmering trade tensions between global superpowers, a rise in international protectionism and uncertainty stemming from the UK’s expected departure from the European Union mean companies are investing heavily to diversify their supply chains and minimise the risk of disruption. Each link in the chain raises a fresh slew of potential risks, but for many, US-China trade wars are the most prominent.

American clothing and footwear manufacturers have been shifting their production away from China to countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia for several years. In recent months the push has intensified in response to President Donald Trump imposing punishing tariffs.

Footwear maker Steven Madden and furniture group RH say they have offset cost increases by shifting some manufacturing operations away from China or negotiating discounts for their continued production in the country.

Others have ramped up shipments of imported goods, stockpiling in anticipation of President Trump’s next move. For the first half of 2019, US ports are now expected to handle 10.7 million containers, a 4.1 per cent increase on the same period in 2018. This could lead to an uptick in warehousing costs and chip away at profit margins.

How UK businesses are Brexit-proofing their supply chains

In Europe, meanwhile, Brexit is causing many corporations to reassess their strategies and supply chains, irrespective of political persuasion.

Sir James Dyson, a billionaire Brexit supporter best known for revolutionising vacuum cleaners, announced in January that his company was moving its head office from the UK to Singapore. He maintained that the shift was not driven by Brexit, but other companies, from Panasonic and Sony to P&O and Schaeffler, have cited the UK’s departure from the bloc as a reason for shaking up their supply chain.

The Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS) estimates that a tenth of UK exporters could have contracts cancelled if there are delays at the border because of Brexit and one in five EU businesses will expect a discount from UK suppliers if border delays persist for a single day.

“The financial cost of Brexit indecision will not be paid in Whitehall, but by Britain’s businesses,” says John Glen, an economist at the CIPS.

Patrick Hogan, director in Rolls-Royce’s global government relations team, says his company has built up additional inventory to manage a potential disruption or delay in supply on account of Brexit.

He adds, however, that the engineering company is less exposed than businesses operating in sectors with high-volume manufacturing, supported by so-called just-in-time supply chains, such as the automotive industry.

Companies can choose to see supply chain threats as opportunities

Like Circulor, tech giant Oracle is one of the companies that has recognised potential threats to global supply chains as an opportunity.

It has developed a product for customers to stress test their supply chains by simulating theoretical scenarios, such as a hard Brexit or an increase in US tariffs. Neil Sholay, Oracle’s vice president of innovation for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, says the product was developed in response to businesses being increasingly fearful of the unknown and wary of who they can trust.

It has developed a product for customers to stress test their supply chains by simulating theoretical scenarios, such as a hard Brexit or an increase in US tariffs. Neil Sholay, Oracle’s vice president of innovation for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, says the product was developed in response to businesses being increasingly fearful of the unknown and wary of who they can trust.

“Whether the risk is geopolitical, social or something else, there’s a growing culture of responsibility in supply change management and businesses will have to keep up to remain competitive,” he says.

Dubai-based port operator DP World is collaborating with Oracle to use microchips to ensure goods are not intercepted and a Dusseldorf-based shoemaker Cano is using blockchain to track the journey of its products, from cow to customer.

Cano’s shoes are produced in Mexico and founders Lukas Pünder and Philipp Mayer say it’s a priority for them to ensure working conditions are fair and that materials are sourced sustainably. Later this year they’ll start offering their tracking technology to other apparel companies.

The founders say geopolitical pressures have so far not really affected Cano’s supply chain, though they did have to halt production briefly in January amid a Mexican government crackdown on fuel theft. “Only a few places were able to get gas during that time,” says Mr Mayer. “That was a huge problem for us.”

Looking ahead, Rolls-Royce’s Mr Hogan says that when it comes to assessing potential risks “the unknown unknowns are always out there”.

“Major disturbances can sometimes flare up from small-scale catalysts, triggering dramatic changes. We protect ourselves to the extent possible, by making prudent choices in the selection and location of suppliers, and by using a selection of forecasting and analysis tools and resources,” he says. “It’s not possible to eliminate geopolitical risk completely, but through these approaches we can minimise the impact on our supply chain and our business.”

Customers increasingly demanding greater supply chain transparency

How US-China trade wars are threatening global business