When Mark Zuckerberg made a foray into virtual reality (VR) back in 2014, he created an industry. In buying the little-known startup Oculus for $2 billion, the Facebook chief executive validated a technology that had for years promised much but delivered little.

Tech giants Google, Sony, HTC and Microsoft quickly followed his lead, a lot of venture capitalists got excited, and a lot of clever youngsters got very rich. VR was going to happen, this time for real.

“Imagine sharing not just moments with your friends online, but entire experiences and adventures,” Mr Zuckerberg declared. “One day, we believe this kind of immersive, augmented reality will become a part of daily life for billions of people.”

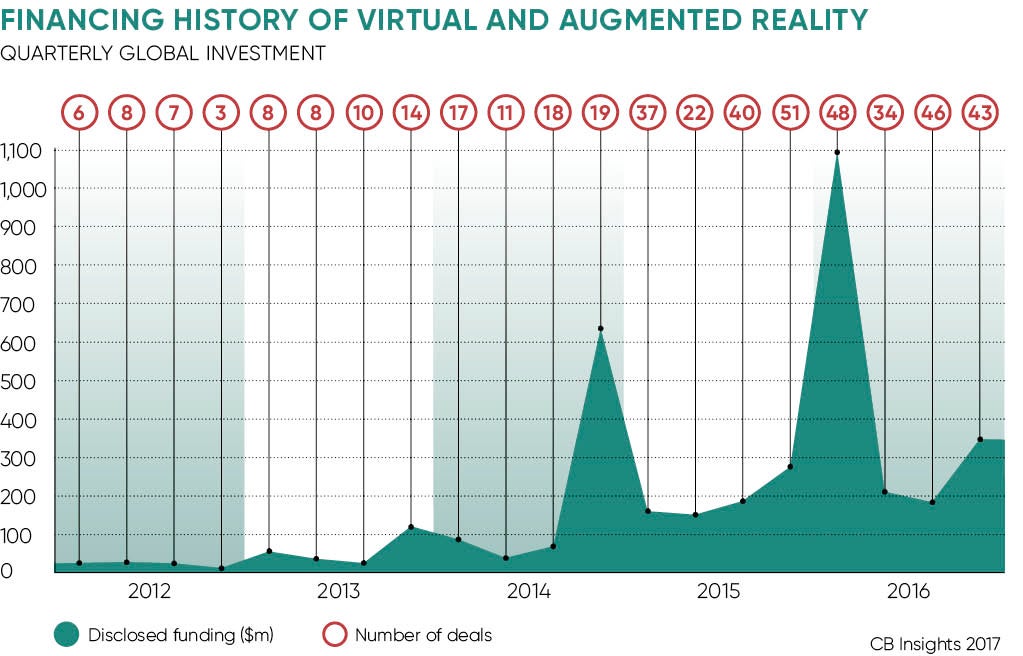

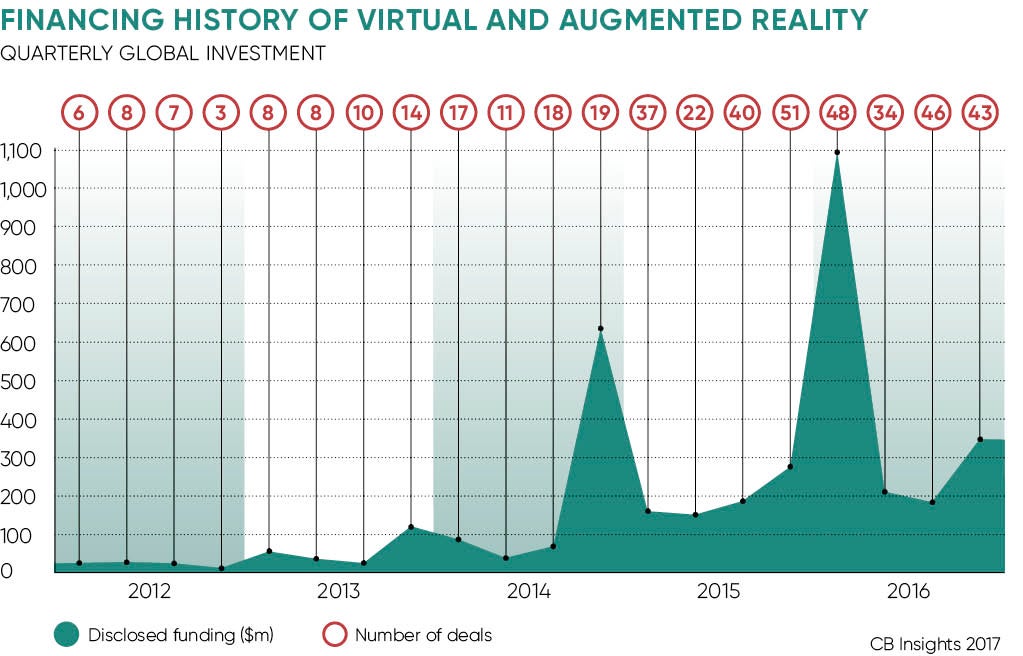

What followed was an arms race, with investment piling into the industry that same year. A slight dip in 2015 left some industry watchers wondering if it was going to live up to the hyperbole. But 2016 put paid to that, with VR funding rebounding to reach $1.8 billion, a 140 per cent growth over the previous year and the largest ever in the space, according to CB Insights.

Big cases

But while others played catch-up, Facebook’s early leap into the future brought with it unwanted baggage. In this case, a lawsuit, the kind that no proud parent-company chief executive wants to hear from his lawyer’s lips: the dreaded “trade secrets”.

What followed was a dispute that has clouded the company’s VR vision, showered Oculus in bad publicity and could even see the company’s flagship Rift headsets banned from sale in the United States.

With an even more public trade secrets fight kicking off this year between Google-owned Waymo and Uber-owned Otto – this time involving driverless-car technology – the issue of who owns the intellectual property is at the forefront of investment in emerging technology.

Facebook’s problems began shortly after the Oculus deal was announced. Video game publisher ZeniMax hit the company with a serious complaint, claiming Oculus executives, some of whom were former employees at ZeniMax, had broken non-disclosure agreements when setting up on their own.

Even worse, the complaint alleged Oculus chief technology officer John Carmack stole documents and source code, later used in the Rift, when he was an employee at ZeniMax-owned id Software and that Facebook knew about it, but went ahead with the deal anyway.

Facebook vigorously denied the claims, but following a major court case in which Mr Zuckerberg himself testified, in January this year a Dallas jury slapped the company with a $500 million fine for intellectual property infringement and “false designation”. In this case, false designation related to the “origin story” for the Rift, which the jury found former Oculus chief executive Brendon Iribe and co-founder Palmer Luckey had lied about.

The issue of who owns the intellectual property is at the forefront of investment in emerging technology

Crucially, the jury rejected the trade secrets element. “The heart of this case was about whether Oculus stole ZeniMax’s trade secrets, and the jury found decisively in our favour,” Facebook said after the ruling.

This didn’t stop ZeniMax from asking a federal judge to block Oculus from using the disputed code in games made for the Rift. If upheld, the move could seriously damage Facebook’s entry into the market it created.

Facebook plans to appeal the original decision and, while it’s unlikely the case will derail its plans for a VR revolution, the company has promised to plough a further $250 million into the project. This certainly piles pressure on the Oculus team, whose poster boy, Mr Luckey, recently quit the company.

If the decision is upheld, damages combined with employee compensation disclosed at the trial, could push the total cost associated with its Oculus acquisition to upwards of $4.3 billion.

The importance of trade secrets

Why was the trade secrets element so important? And what can Silicon Valley investors, including those with shallower pockets than Mr Zuckerberg, do to avoid finding themselves in court?

“Trade secrets are the hardest form of IP to diligence because they are not registered with any governmental authority and very often are not even recorded in any tangible medium,” explains Dror Futter, a partner at US law firm Rimon, specialising in advising emerging companies and their investors. “At the same time, a venture built upon misappropriated trade secrets is at much at risk as a venture that infringes a third-party patent.”

Under the recently enacted US Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016, a trade secret owner can recover a combination of actual losses, unjust enrichment and/or a reasonable royalty. Hence ZeniMax’s damages award reached the half-billion-dollar mark.

The law also means that, in certain circumstances, a trade secret owner can obtain an injunction against the product in question, preventing it from being sold.

“Recently, an increasing number of M&A deals include the purchase of representation and warranty insurance for the benefit of the buyer, which covers liabilities arising from a breach of a representation or warranty,” says Mr Futter.

Whether any such contracts would have influenced the Oculus case is open to debate. But one thing is certain, while the ZeniMax v Oculus litigation rumbles on, competitors like Microsoft’s HoloLens, Qualcomm-backed Magic Leap and GoPro are free to develop their systems without distraction, making gains over Facebook’s first-mover advantage.