For centuries the importance of sleep in keeping us energised and healthy has been well noted. Just ask Benjamin Franklin who once remarked “early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise”. However increasingly it appears that sleep isn’t just responsible for keeping us going, but also for powering the global economy.

Take productivity, the economic measure of how effective we are at work.

According to a report by Cambridge University and Rand Europe, commissioned by Vitality Health, lack of sleep is the biggest driver of low productivity in the work place. It found that workers who slept for six hours or less a night were notably less productive than those who managed to get around seven or eight hours’ sleep.

So when workers sleep less, they work less and this has profound implications for macro-economic performance. In the US alone, for example, the Harvard Medical School found that a lack of sleep costs firms a total of $63.2bn each year.

This was not due to sleep related absenteeism; but rather poorer performance from workers who still turned-up. As another expert put it, “If we treated machinery like we treat the human body, there would be breakdowns all the time,” said James Maas, a former Cornell University psychologist and author of “Sleep for Success. ”

Focus on Britain

Nowhere is the economic impact of poor sleep more evident than in Britain, a country which has been plagued with low productivity since the financial crisis of 2008. Indeed, while there have been tentative signs of productivity gains in recent years, the UK continues to lag behind many of its G7 rivals. In fact, the UK on average produces around 30 per cent less than the Germans, French and the Americans per hour. “The UK still has a major productivity problem”, says Tony Manwaring of the Chartered Institute of Management Accounts. “It is unacceptable that it takes four British workers to deliver the same output as three Americans.”

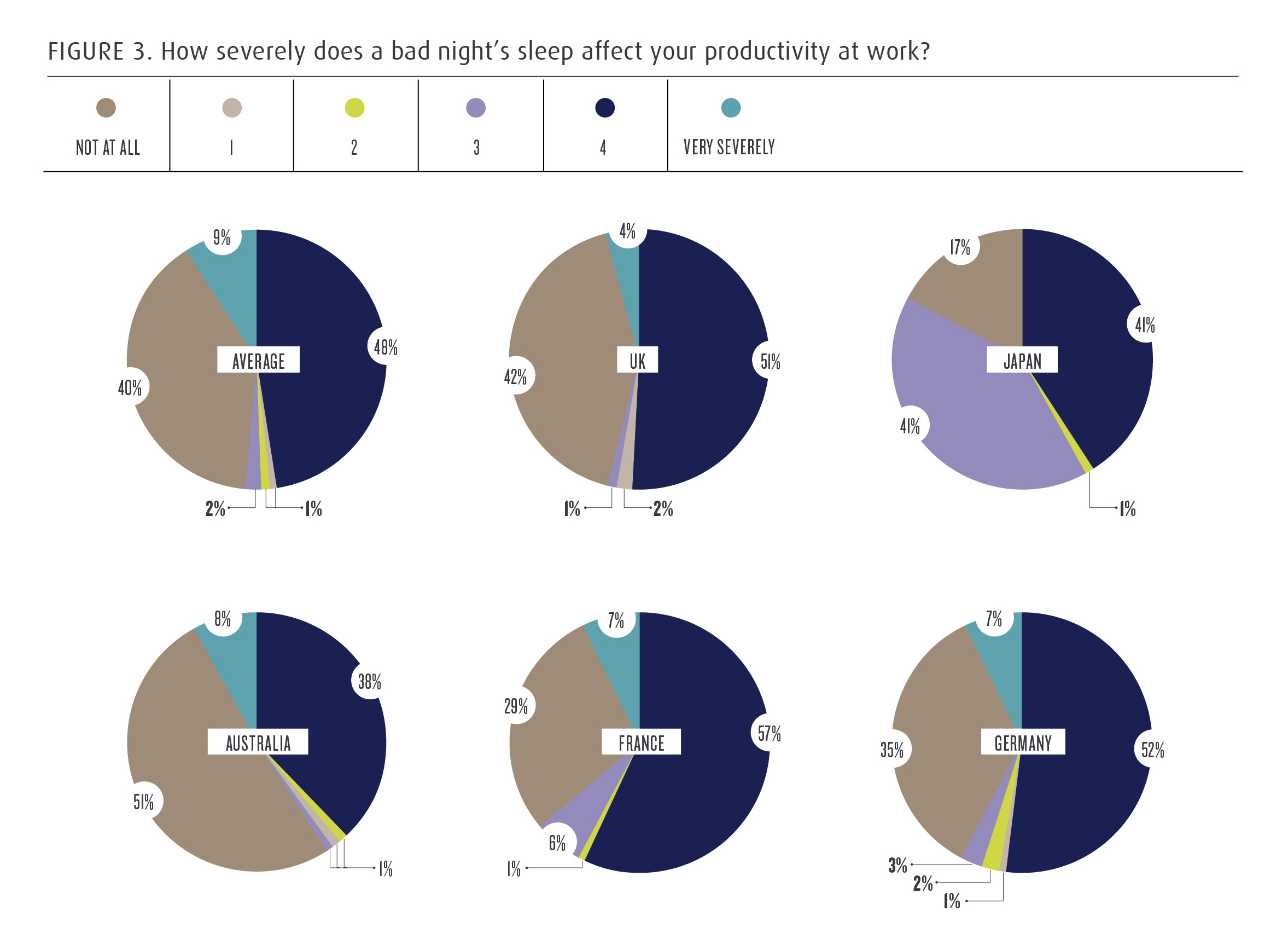

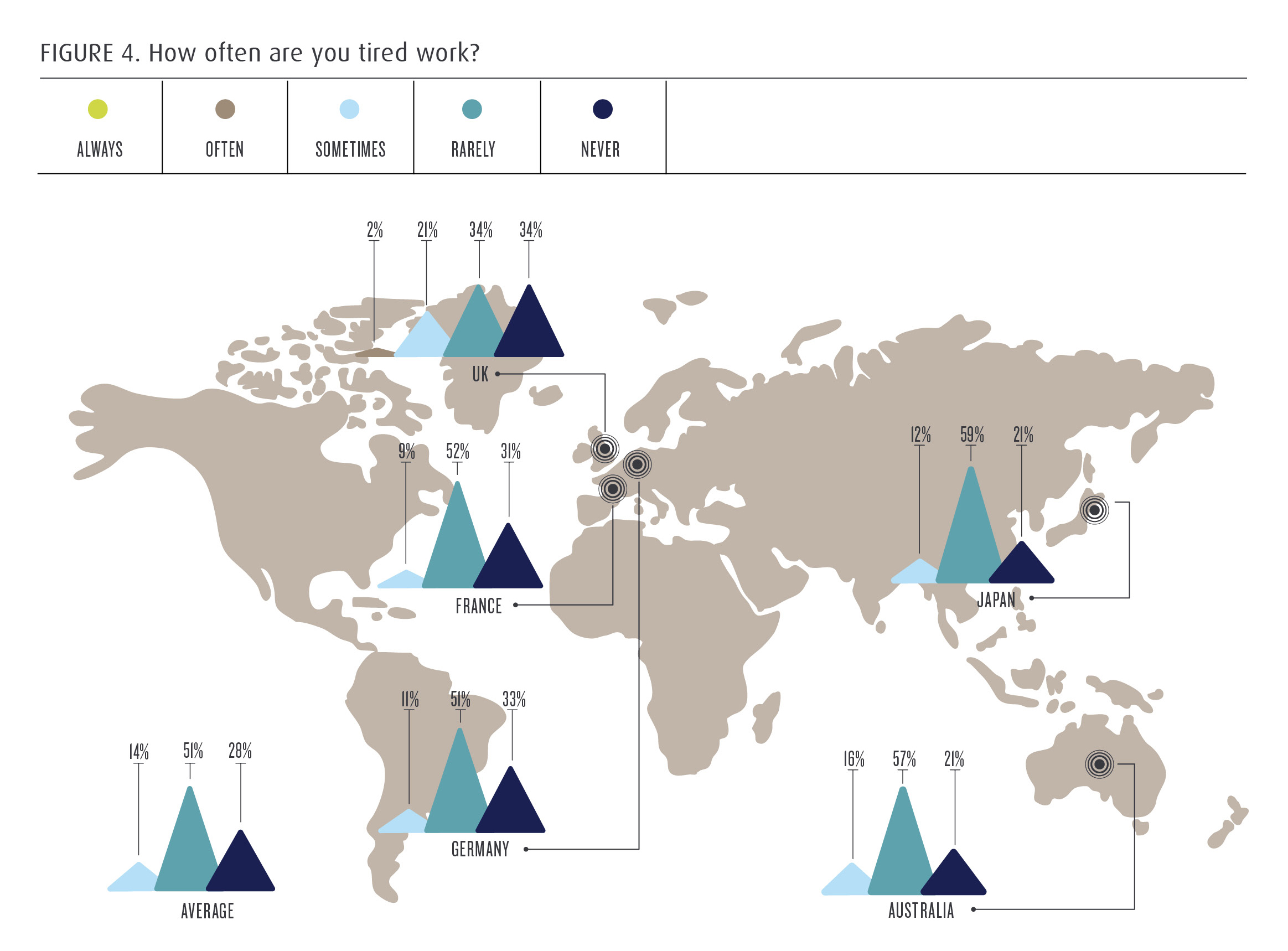

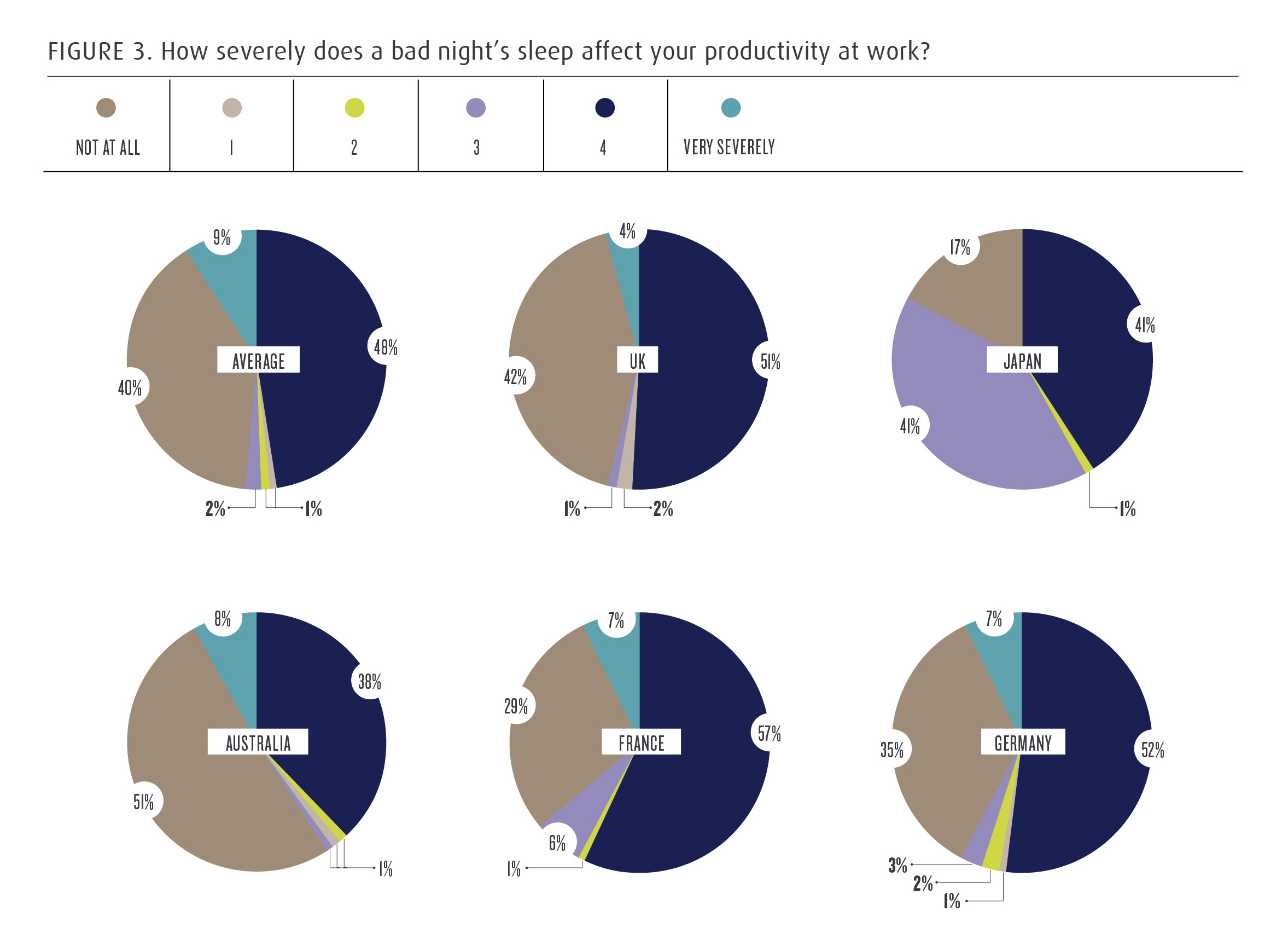

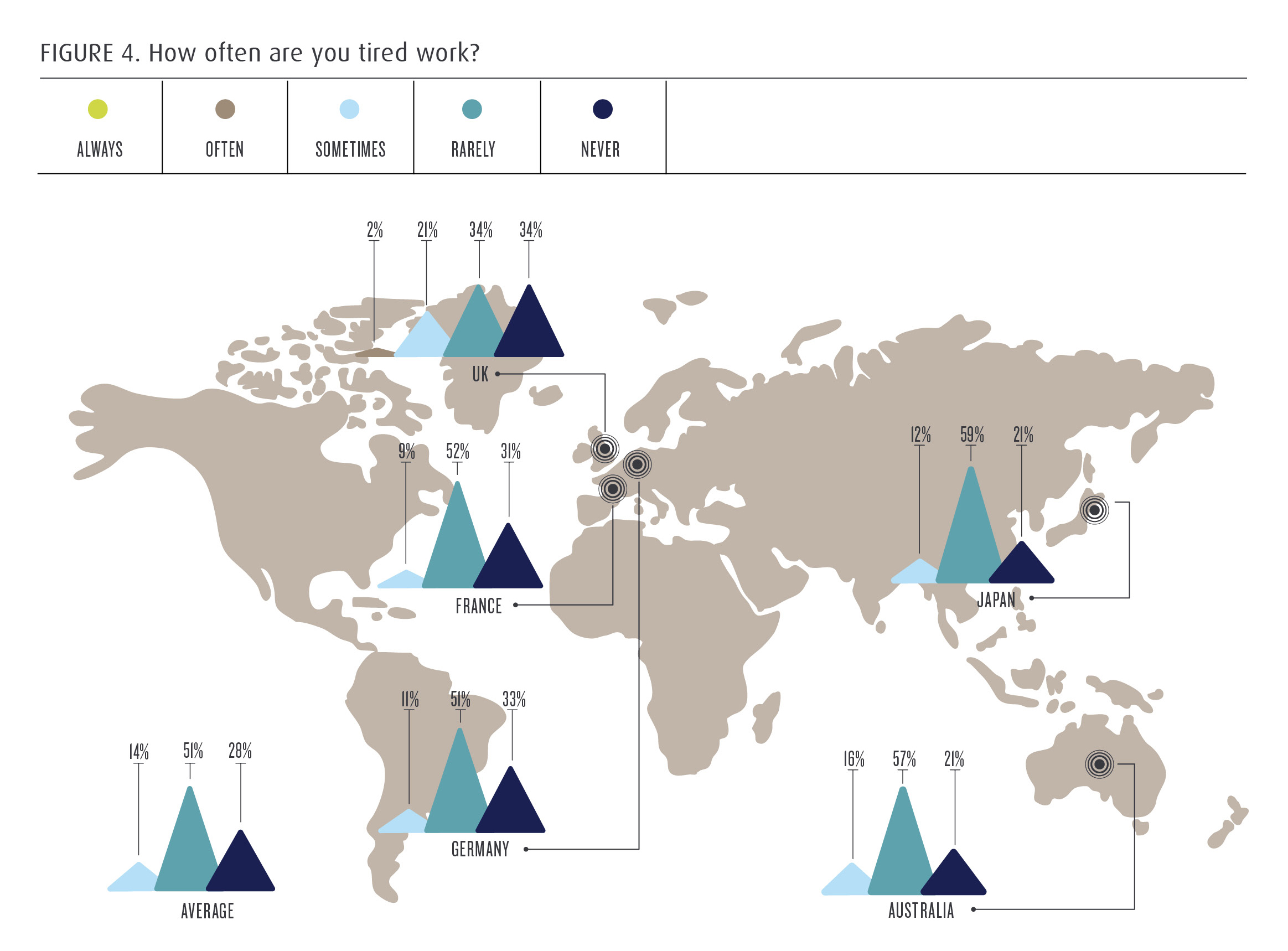

Given this, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Britons finished bottom in almost every category of Tempur’s research. In fact, British workers were the only cohort surveyed to admit to being ‘often’ tired at work, with around 8% of Brits missing one or more days of work due to tiredness. This is in stark contrast to German employees, of whom only 1% admit to missing work due to bad sleep.

And what’s more, the impacts of poor sleep are also more acute for British workers than others - 46% reported that poor sleep ‘severely’ or ‘very severely’ impacts their ability to focus at work, versus 10% of all other nationalities surveyed.

The reason why Britons seem to sleep less and suffer more from bad sleep could lie in the fact they go to bed later than other nationalities. In the UK 48% of respondents to Tempur’s survey went to bed between 11 and 12pm, with 2% turning-in even later. Meanwhile in Germans 42% went to sleep between 11 and 12pm, with no one going any later. Similarly, in Japan, no respondents reported going to bed after 12pm.

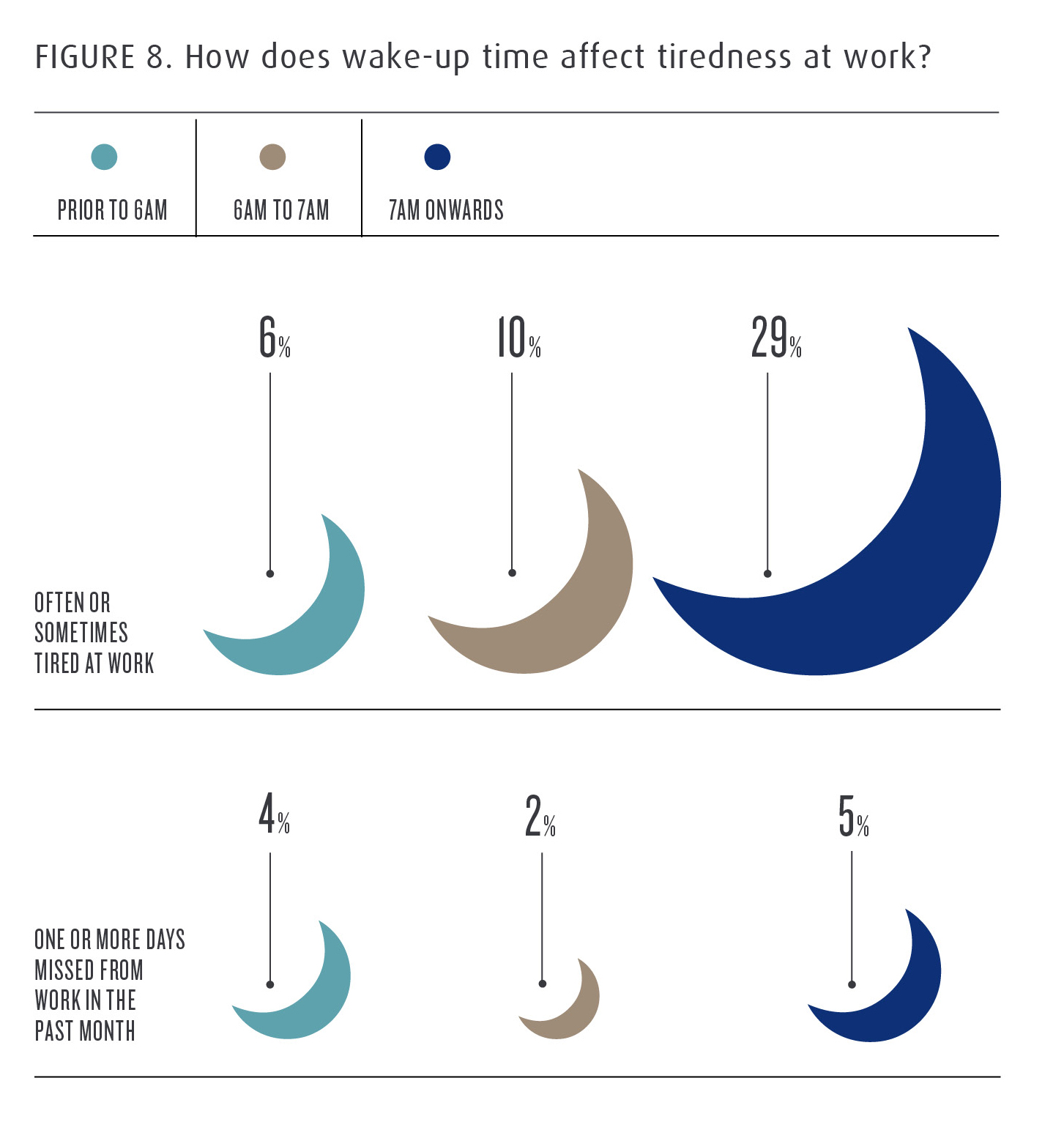

With their later bed times we might expect British workers to wake-up after other nationalities.

In reality, though, Tempur’s study shows that British workers are actually the second earliest risers of all respondents surveyed. French workers were the first to wake-up in the morning with 75 per cent getting up before 7am, followed by British workers (70 per cent), compared to 67 per cent in Germany, 65 per cent in Japan and 59 per cent in Australia.

Taken together it appears that this combination of late nights and early mornings are costing the British economy and workers dearly. In fact, according The Resolution Foundation, a low pay think-tank, unless the UK witnesses a significant lift in productivity, wage growth could slow to below 1 per cent by the end of this year.

Tiredness leads to procrastination

It seems intuitive that tiredness hampers focus and brain function at work; but studies also show that a bad night’s sleep has other behavioural impacts on productivity.

According to the Singapore Management University, for example, workers are much more likely to waste time surfing the internet when they haven’t had enough sleep. This phenomenon, labelled ‘cyberloafing’, leads to even lower levels efficiency in the workplace.

And while a few minutes of personal web surfing now and then may seem harmless, given that about one-third of the world’s countries participate in some form of daylight saving time, the researchers warned that “global productivity losses from a spike in employee cyberloafing are potentially staggering.”

The impacts of bad sleep for both macro and micro economic performance are then both far-reaching and severe. Given this governments and policy makers would do well to educate and encourage citizens to sleep better. A good night’s sleep could just be the answer to global productivity nightmare.

Focus on Britain