Though it might seem contradictory in our fast-moving 24/7 society, the idea that “sleep is for wimps” is long gone. The world’s smartest CEOs definitely do not allow themselves to run on

empty, says Bradley V Vaughn MD, professor of neurology and biomedical engineering, at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. “We see in our research that the Fortune 500

folks do well in sleep. They know when to use short-term strategies such as caffeine fixes to push through, but equally understand they’re not helpful for long-term success.’

But could it be that Brits, for example, still harbour an outdated, 80s attitude to shut-eye? UK respondents rated their quality of sleep as worst of all. 8 per cent graded their sleep as moderate to very poor, whereas 97 per cent of the German and French ticked the good or very good boxes.“By far the biggest misconception is that we can get by on sleeping less,” points out Mary Ellen Wells, director and assistant professor of neurodiagnostics and sleep science at the University of North Carolina. “But everyone and everything needs sleep, from humans down to the fruit fly.”

But could it be that Brits, for example, still harbour an outdated, 80s attitude to shut-eye? UK respondents rated their quality of sleep as worst of all. 8 per cent graded their sleep as moderate to very poor, whereas 97 per cent of the German and French ticked the good or very good boxes.“By far the biggest misconception is that we can get by on sleeping less,” points out Mary Ellen Wells, director and assistant professor of neurodiagnostics and sleep science at the University of North Carolina. “But everyone and everything needs sleep, from humans down to the fruit fly.”

On one level, it’s a very simple, basic function, as essential to life as eating and drinking. Animals who go without sleep for 21 days suffer multi organ failure and pass away, says Vaughn. More subtly, we need to take sleep seriously because it regulates all the processes in the body. For centuries, we’ve been aware of the restorative qualities – overnight, the body’s systems rest and recharge while very few calories are burned. Now, with advances in science, we’re understanding more about the highly complex cascade of hormonal shifts, brain processing and memory consolidation that happen during the night.

Sleep is as important for mental health as it is for the physical

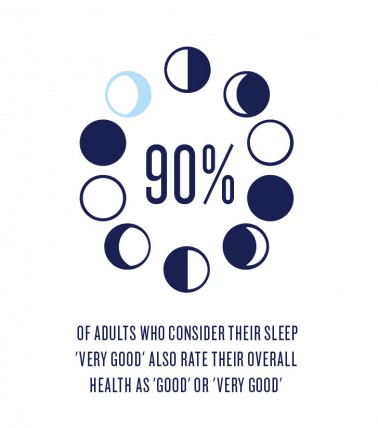

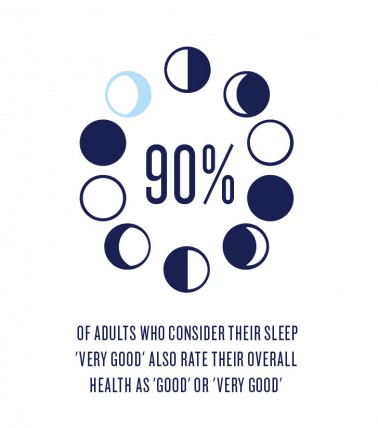

“I’m a neurologist, so I am biased, but generally sleep is as important for mental health as it is for the physical,” explains Vaughn. “The body supports the brain and the mind, and good-quality sleep is required for both.” Interestingly, the record for a human going without rest is 11 days, after which states of psychosis set in. That’s extreme, but most of us have experienced the short fuse effect on our temperament when we’ve had a late one. And it seems our loved ones feel the brunt – 28 per cent of the survey respondents say that a bad night caused severely increased irritability in personal relationships. Conversely, 80 per cent of those surveyed who report not being stressed at all enjoy very good sleep.

It being one of the most natural things to do in the world, most of us wouldn’t dream of deliberately denying ourselves shut-eye. However, modern life often conspires to subtly sabotage our sleep. We all have an internal body clock – our circadian rhythm – that is affected by such things as artificial light, international travel, our activity levels as well as by what we eat and drink.

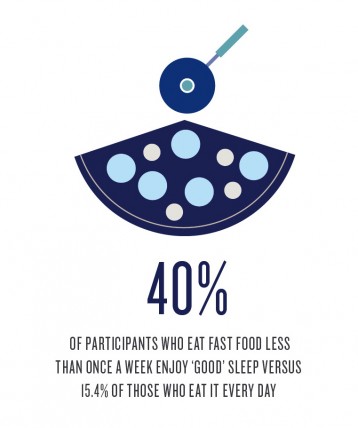

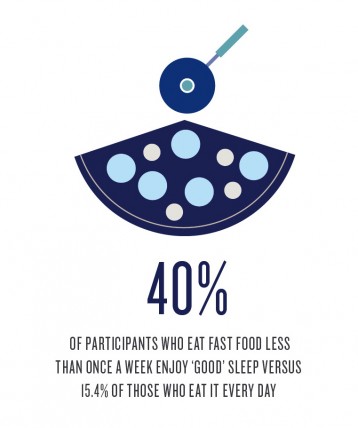

And talking of food, hold fire on that takeaway, since 40 per cent of participants who eat fast food less than once a week enjoy good sleep versus 15.4 per cent of those who eat it every day. “Anything we take into our bodies has the potential to disrupt sleep,” says Wells. “It’s very personal. For some, it’s eating heavy or spicy meals close to bedtime, for others it’s sugary foods. Food sensitivities can be another issue, and people may not even realise they have them. Even drinking water can interrupt sleep for those who have to get up often to urinate. The list is endless.”

And talking of food, hold fire on that takeaway, since 40 per cent of participants who eat fast food less than once a week enjoy good sleep versus 15.4 per cent of those who eat it every day. “Anything we take into our bodies has the potential to disrupt sleep,” says Wells. “It’s very personal. For some, it’s eating heavy or spicy meals close to bedtime, for others it’s sugary foods. Food sensitivities can be another issue, and people may not even realise they have them. Even drinking water can interrupt sleep for those who have to get up often to urinate. The list is endless.”

Maybe it’s no surprise to gym enthusiasts who love nothing more than a post-work gym session followed by healthy dinner and bed that nearly 70 per cent of those in the survey who exercise three times a week experience very good sleep compared to only 13.8 per cent who exercise less than once a week. And while turning in early isn’t being touted as the latest weight-loss trick (as far as we know) – sleep-deprivation seems to trigger the hunger hormone ghrelin to be released, sending signals to the brain to seek out quick-fix energy foods – in other words sugary carbohydrates. This type of weight gain is a well-documented chronic stress response in the body to lack of sleep, says Vaughn.

For optimum rest and therefore maximum wellbeing, “the most important thing is to align our body clocks with our sleep times”, continues Vaughn, who recommends that first of all we discipline our schedules to wake up and go to bed at the same time seven days a week (those weekend lie-ins are the equivalent of jet lag). Having consistent meal times, also helps, adds Wells – including not getting up to eat during the night and not skipping breakfast.

For optimum rest and therefore maximum wellbeing, “the most important thing is to align our body clocks with our sleep times”, continues Vaughn, who recommends that first of all we discipline our schedules to wake up and go to bed at the same time seven days a week (those weekend lie-ins are the equivalent of jet lag). Having consistent meal times, also helps, adds Wells – including not getting up to eat during the night and not skipping breakfast.

A couple of last gems from the survey: men are significantly more likely to check emails pre-bed (74 per cent) versus women (48 per cent), and, warns Vaughn, bright light in blue wavelengths (emitted from those ever-present screens in our hands, homes and offices as well as from energy-efficient lighting) has the most impact on our body clocks. Interestingly, only 4 per cent admit to having “intimate relations” before sleeping – perhaps it’s worth rethinking that one?