Like most centennials, Nicole is into her music and her gadgets. Unlike most of her peers, however, she struggles to access either very easily.

Twenty-one-year-old Nicole suffers from cerebral palsy and scoliosis, a dual condition that causes her muscle weakness and severely limits physical mobility. Simple actions like getting up to retrieve a CD or bending down to plug in her speakers prove problematic.

But pass her room at Beaumont College, a residential education facility in Lancaster, and there’s every likelihood you’ll hear the latest Jonas Blue or Sam Smith album blaring out.

How come? Easy, she now has someone, or something, to help her. Meet Alexa, Amazon’s cloud-based virtual assistant or smart bot. You can’t see Alexa, but you can ask her to play your favourite track and she will happily oblige, as long as you have a hands-free Amazon Echo speaker to hand, that is.

Devices such as the Amazon Echo are empowering disabled users to live more independent lives

Alexa is just one of hundreds of smart-tech solutions that are finding their way into our homes. Think fridges that automatically reorder food items when your supplies are running low or beds that adjust to your sleeping patterns or intelligent ovens that cook to spec.

For most of us, the arrival of internet-enabled mod cons provides some welcome extra convenience, observes Richard Lane, head of communications at disability charity Scope. But for disabled people, it can be “genuinely life changing”.

Technology can help disabled people increase control over their own lives and live independently

It is an argument that Fil McIntyre is quick to endorse. Lead assistive technologist at Beaumont College, one of four specialist further education facilities run by Scope, he recently introduced a small-scale trial of Amazon Echo for resident students.

The trial also sees selected students gain access to voice-activated automation hardware that enables them to control lighting, heating and other home systems through speech.

“The potential of this kind of technology for people with disabilities is outstanding,” says Mr McIntyre. “To be able to ask a device to turn a light on or unlock your door, say, is just so enabling for people with disabilities.”

He’s not doe eyed, mind. To get the most out of smart-home tech, it usually requires syncing multiple devices, something that is “not very straightforward” for those without the support of a technical expert.

Just accessing a device itself can represent an even greater impediment. In the vast majority of cases, smart-tech products are built and designed for the mass market. As such, the chances are high that the text might be too small for a visually impaired person, for example, or the buttons too fidgety for someone with manual dexterity problems.

Yet this second problem is one that leading manufacturers are becoming increasingly sensitive to, according to Robin Sparks, innovations and technology relationships manager at the UK sight-loss charity RNIB.

Mr Sparks singles out brands such as Google, Amazon, Apple and Samsung for leading the way in what he terms “inclusive design”. He cites the iPhone, iPad and Apple Watch, which all include accessibility functions as standard. Likewise, screen readers can be found across Amazon’s complete product range of electronic products, from the most basic Kindle to the highest-end Fire tablet.

In such cases, accessibility is “baked in”, says Mr Sparks. “It’s not seen as a secondary consideration that might mean the additional fitting of hardware or software.”

Not all technology companies are so forward-thinking, however. To help the smart-tech industry up its game, RNIB offers a paid-for advisory and testing service for manufacturers around the world.

The charity’s list of recent clients includes the South Korean tech giant Samsung. The pair have been working for the last two years to reimagine what a smart television might look like for a blind or partially sighted consumer.

As a result, Samsung’s latest range of smart TVs allow users to magnify content, change the colour contrast and hear any text read out loud in high-quality synthetic speech, among many other features.

A lack of understanding about the needs of disabled or infirm users is part of the problem

Although most tech companies acknowledge the importance of inclusive design, not all “practise what they preach”, says Mr Sparks, who himself has low vision.

The reasons for this are multiple. A lack of understanding about the needs of disabled or infirm users is part of the problem, as is a lack of internal expertise on how to meet such needs.

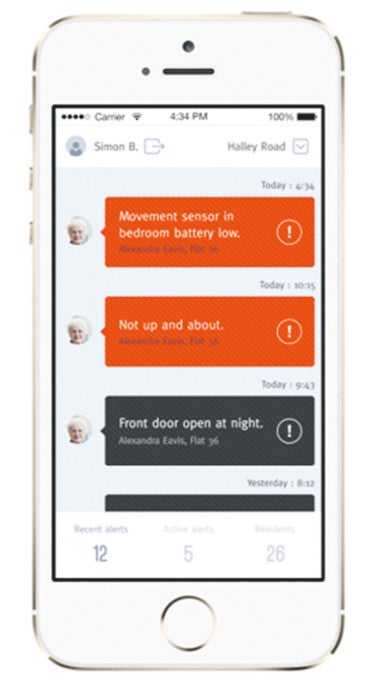

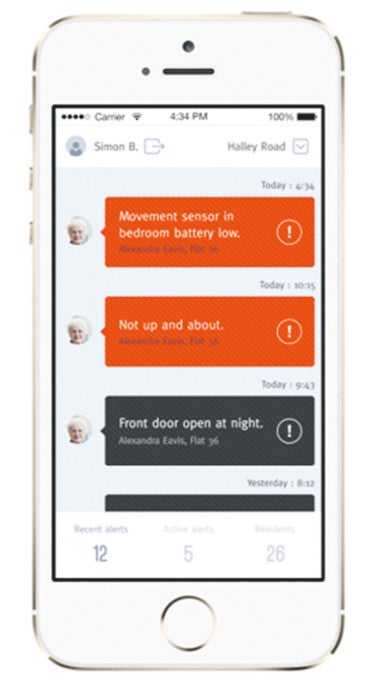

Smart-home sensors by assistive technology company Alcove can send automatic alerts to loved ones or carers

But much comes down to numbers. Fewer than one in ten European adults have a disability (70 million of 743 million), of whom fewer than two fifths (36.9 per cent) use some kind of assistive technologies. That’s still a lot of potential customers. But for multinational tech firms gunning for the mainstream market, the disabled segment remains a niche.

Specialist technology developers and disability experts are combining to help fill this gap, however. Take the Global Disability Innovation (GDI) hub, for instance. Born out of the London 2012 Paralympics, the initiative is bringing businesses, academics and charities together to design smart-tech solutions for people with disabilities.

One of the GDI hub’s first projects has been to connect wheelchairs in India to the internet of things. The resulting data has enabled the development of maps detailing wheelchair accessibility.

So does a technology-empowered nirvana now await disabled users? Not necessarily. Smart tech requires smart solutions, naturally. But it also requires a smart healthcare system and there lies one of the major hurdles ahead.

At present, agencies providing care services to disabled or infirm individuals in their homes have precious little incentive for promoting the uptake of smart tech, says Robert Longley-Cook, chief executive of Hft, a UK charity working with people with learning difficulties.

At present, local authorities and others commissioning care pay service providers on an hourly basis. No provision currently exists to invest in smart-tech solutions. Furthermore, if those solutions end up making care provision more efficient, then less care hours will be needed, leading to a reduction in service providers’ revenue.

“As long as local authorities commission care by the hour, your only output will be an hour’s worth of care. This restricts what we can do,” says Mr Longley-Cook.

According to Hft, a far better system would be to allow care providers to retain any savings achieved through the introduction of smart technologies. This could then be reinvested in staff, technology and more innovation, the charity argues.

Hellen Bowey is of the same opinion. Chief executive of Alcove, a software aggregator firm that promotes independent living, she says the UK care industry is “Victorian” in its adoption of smart tech.

“The technology is all there. And the devices are just getting better and better,” she says. “So all it takes is for people to start joining the dots.”