Q: Does the pandemic provide an opportunity to rethink how businesses approach climate change risk?

LF: Both climate change and COVID-19 are an outside shock to the system. Both cause massive disruption and have a non-linear impact and multiply risks. And they both hit the most vulnerable the hardest. So there’s an enormous number of lessons that we can learn. Of course, it’s different in that climate change does not spread like a virus, but its impact does accumulate. Also, we shouldn’t underestimate the link between disease and climate change. For instance, by 2080 global warming could expose nearly one billion more people to tropical, mosquito-borne diseases in areas such as Europe.

MM: I think there’s going to be a greater understanding that we’re going to listen to the collective view of science, at an individual level, as a society and at corporations. If you watch the British government’s daily COVID-19 update, we have a politician who says a few words, but most of the discussion is coming from medical officers and scientists. Hopefully, if we listen to scientists we will start making changes instead of looking at predictions of what will happen in ten years, taking them with a pinch of salt and kicking the problem down the road. The current crisis also highlights the interconnected nature of risk. There needs to be new thinking on how we use the past to predict the future and new modelling techniques that can show the real impact. For climate change, we might be talking of the sea level rising one metre or more, but what does this truly mean to individuals, companies, governments and the ecosystem?

You can’t sleepwalk into another problem that is potentially of a magnitude bigger than COVID-19

RC: Climate change is a risk multiplier, amplifying existing risks in areas like food, water and energy security. Mass displacement of people because of sea-level rises caused by climate change threatens political stability, and extreme weather endangers the safety and resilience of the critical infrastructures that modern societies depend on. So the current crisis teaches us some lessons that can be carried across, such as the importance of international collaboration and assuring the resilience of supply chains. We can also learn a lot from the crisis around the public understanding of risk and behavioural sciences.

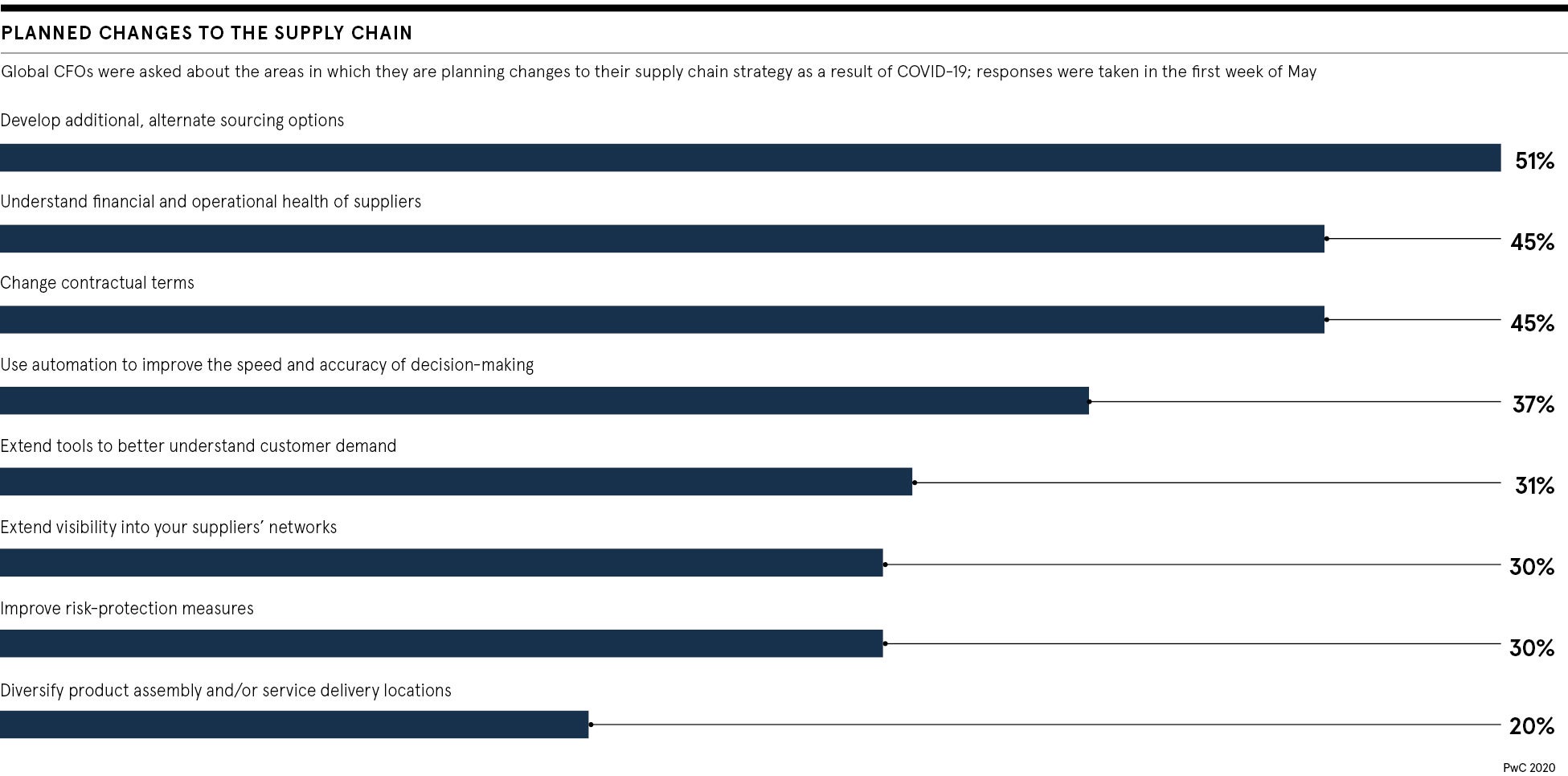

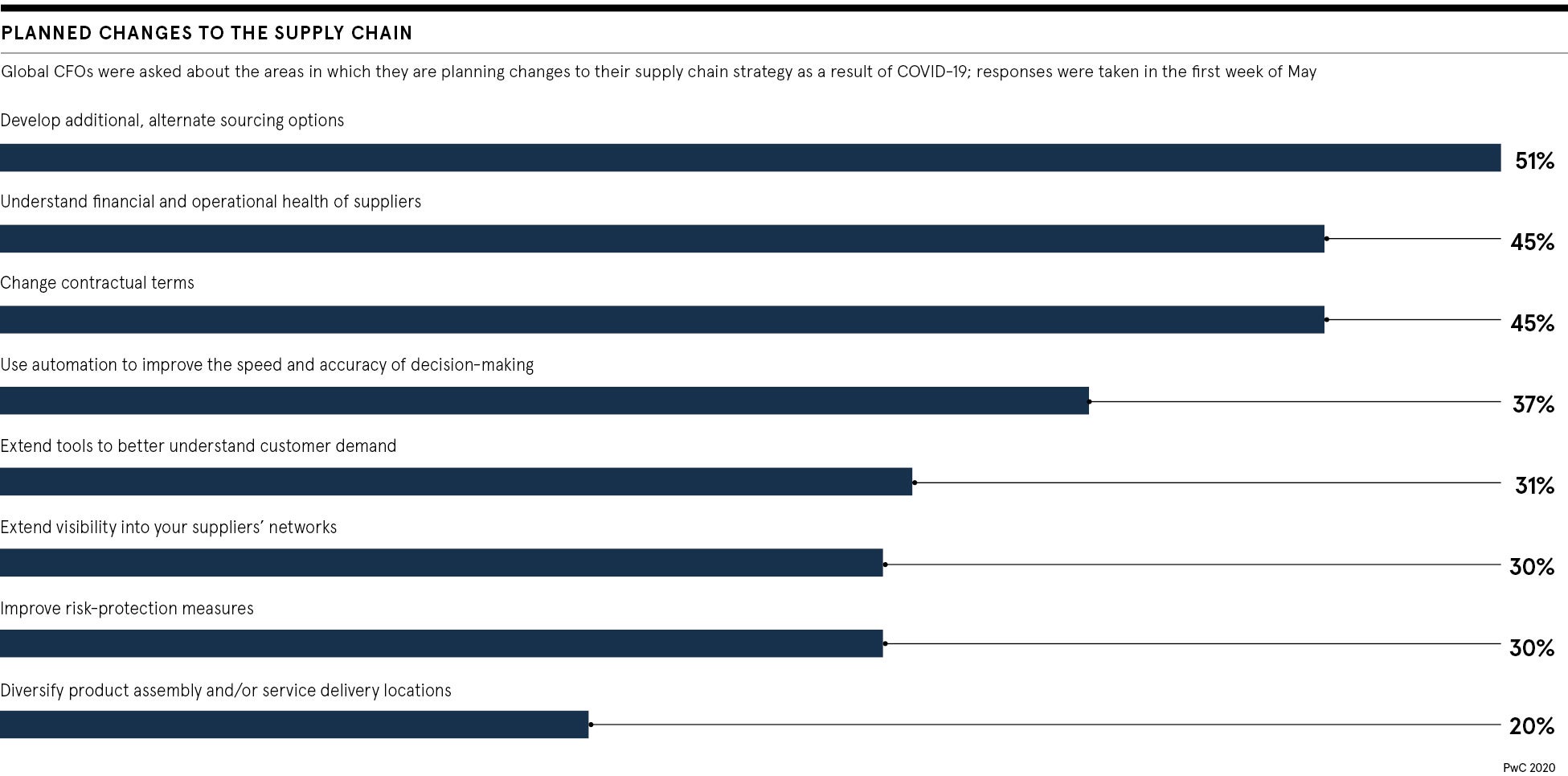

Q: How will companies’ view of the supply chain evolve?

SM: I think there may be more inshoring. That may be done to reduce risk, but potentially there is an environmental upside to this as well, not having things transported all around the world.

RC: The thinking to date on supply chains has been around cost and efficiency. I think we’ll see supply chains a lot shorter and increased focus on resilience, reducing complexity. Assuring the provenance and traceability in supply chains is a growing matter.

RH: If you want to shorten supply chains, you may need collaboration. For instance, if you want a sub-contractor to move production from China back to the UK, you may need collaboration with other organisations to ensure there’s enough demand for it.

Q: Will planning for climate risk be a luxury companies battling for survival can’t afford?

SM: It’s going to be hard, but it’s necessary. You can’t sleepwalk into another problem that is potentially of a magnitude bigger than COVID-19. I think people may be more prepared to try new risks and be less afraid to fail.

JL: The more you want to increase risk, the better your risk management needs to be. As businesses become more ambitious, then poor risk management becomes a limiter. Companies become accident prone and vulnerable. Resilience will be sought after.

JG: I hope the focus on climate change will come back, among other emerging risks. But all of these risks should be discussed around the boardroom table rather than being ranked, put into a ring binder and maybe thought about twelve months later. All too often people see lists of risks and debate their ranking, rather than asking “What does this mean for us and how must we change to be resilient and advantaged in the future environment?” It’s key for boards to consider high impact, but low probability risks alongside the risks that do make it into their risk register. Emerging risks, such as climate change or pandemic, demand a different way of thinking, more future-gazing and more frequent discussion.

Q: So, will boards become more interested in risk?

JG: Every time we’ve seen a new risk in the last few years, we always say it will make the board spend more time managing risk. But then every report I read about the allocation of board time to risk shows it has stayed the same, about 5 per cent. Given the connectivity and the strategic importance, both in climate change and COVID-19, hopefully more time will be given to talking about risk.

RC: A question is whether boards have the relevant skills to manage growing technology-related and environmental risks. A recent review by Grant Thornton reported that technology skills are increasingly being brought on to the board in recognition of this. The current crisis has shown the public trust put in scientists and the importance of science and evidence-based decision-making. I imagine there will be increased attention to “tail risks”, events with a low probability but with high consequences.

JL: Boards like to focus on things they feel they can influence and things like climates change and external shocks are not. Therefore they put them into the “too hard” pile. Boards are better at investing time in risk management than crisis management. If the board doesn’t know the answers it’s OK, but they must surround themselves with people who do. They can hire somebody who knows what they’re doing, put them into middle management somewhere and tell them to come back with the answer.

MM: I wonder whether, as a result of what’s happening with COVID-19, maybe the accounting establishment will look at more disclosures, such as asking for a statement from the board about their crisis management capabilities, their resilience capabilities. Investors are looking for companies that are a good long-term bet and have the agility to respond to a crisis outside conventional models.

Q: Does the current crisis show company silos need to be broken down?

JL: More of our world is connected than ever before. You have to manage with your peers, other stakeholders. Nothing these days works as a silo.

SM: Maybe the video-conferencing technology we’re using may help. It’s now easier to get people together at short notice, rather than trying to find space in diaries, speaking to PAs, travelling to meetings; maybe it’s an enabler.

LF: It’s so important that within companies the risk managers are connected closely to the sustainability managers so we have both a short-term and a long-term risk perspective.

Q: Have risk managers lost credibility because they didn’t predict this crisis?

RH: There is a chance it switches round, from losing credibility to gaining credibility, showing how we can help the business understand the risks today, next month and in the coming years. There are signs the board will make more contact, asking “Do you think the business has sufficient risk management plans in place? Do you think they’re credible?”

JG: We knew the risk was there: the World Economic Forum Global Risks Report has had it for the last ten years, although it was down at the bottom because the probability was low even though the impact was high. Back in 2006, sponsored by the Bank of England, the City of London had a pandemic rehearsal because the financial services sector thought there was a serious potential problem. So people have known about the risks. But it has fallen off the radar because people don’t like spending money and time on improbable incidents.

RC: Some traditional predictive theories have been shown not to work. Maybe it’s time to move away from modelling and predicting events to admitting things are going to go wrong and just creating a general resilience in the system.

It’s so important that the risk managers are connected closely to the sustainability managers so we have both short- and long-term risk perspective

RH: In our business, every year we conduct a ten-year viability plan and include a number of shocks and stresses. COVID-19 was not among them, but there were other shocks and stresses and that allowed us to understand the size of our financial buffer which has now been utilised.

LF: On modelling, that’s something we insurance companies are already working on. We rely on CAT models [standard computer models used by insurers to predict losses from extreme weather based on historical data] but they are not really going to help us understand the physical risks caused by climate change. So we are now working on climate change models that can have a more forward-looking view and help customers understand things like where they put physical infrastructure and the risks of that location. That’s very high on our agenda.

Q: Are there positive lessons from the pandemic?

RH: We should use COVID-19 as an opportunity to apply innovation to how we think, plan and act in the future.

SM: I think the coronavirus crisis has taught us that if there’s a genuine sense of urgency, we can do things really quickly. There’s potentially a vaccine being developed in months and not years. You have companies collaborating to make ventilators, something they have never done before, in timescales that were previously unthought of. If we can bring some of this attitude, thinking and collaboration into tackling climate change, we could make a big difference.

JG: We have to squeeze out all the lessons we’ve learnt. As companies and countries, we’re not always very good at doing that. We are all too quick to get on to the next thing. We must take time to reflect.

Q: Does the pandemic provide an opportunity to rethink how businesses approach climate change risk?

Q: How will companies’ view of the supply chain evolve?

Q: Will planning for climate risk be a luxury companies battling for survival can’t afford?