Fraud committed by insiders is a large and growing threat to companies. Systems that monitor abnormal behaviour have become a major weapon in the fight against the threat of insider fraud. But many companies are behind the curve in adopting such systems.

Here are two examples of how “behaviour intelligence” technologies are saving companies millions from the insider threat.

A US bank found that a new employee had been typing questions into Google frequently about how to do their job, much more so than any of their peers. The company’s security system flashed a warning signal about this abnormal behaviour. It was revealed that the employee was a fraudster who had fabricated their experience to get the job so they could access the company’s data.

Another bank employee was found to have been creating unusual spreadsheets with data taken from business systems, again through a warning signal about abnormal behaviour from its security system. By checking the data against the company’s financial statistics, the bank discovered they and another individual with privileged access were insider dealing.

Enabling early visibility, with a fast signal into abnormal behaviour can help to eliminate or reduce that insider threat

Organisations that fall victim to fraud on average see their share price fall 5 per cent on the day a breach is disclosed, according to the Ponemon Institute. Falls range from 3 per cent for companies with good security to 7 per cent for companies with poor security. The average cost to organisations is $8.7 million (£6.8 million) per incident.

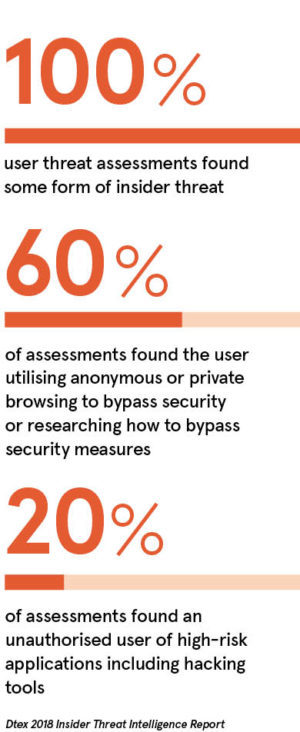

One of the biggest problems companies face in protecting against fraud is the insider threat; 60 per cent of all attacks are carried out by insiders, according to IBM. The Dtex 2018 Insider Threat Intelligence Report revealed that 100 per cent of all organisations assessed have active insider threats in play.

To make matters worse, 76 per cent of insider incidents are not prosecuted, due to lack of evidence.

Many companies in banking and other industries are failing to detect or prosecute insider frauds because their security systems lack visibility on suspicious activity. There are thousands of abnormal behaviours that may indicate a potential fraud. Behaviour intelligence technology is effective because it can provide an early-warning signal for prevention and forensic evidence if an act is committed.

The insider threat is often from privileged users, who are employees, contractors or partners with access to almost every corner of the corporate network. These individuals do not need to use sophisticated hacking software. They can often execute a fraud with existing software that is familiar to them.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force this year, could have unintentionally made this situation worse by making it more attractive to criminals to plant or bribe an insider to misappropriate data, with privileged users being primary targets.

GDPR mandates heavy fines for companies that suffer a data breach. Penalties can reach up to 4 per cent of a violators’ annual revenue, which in many cases will far outweigh the actual cost of a breach.

Rather than sell stolen data to fellow criminals or exact a ransom to unencrypt it for smaller amounts, criminals will extort money from organisations for not exposing data thefts publicly, which would trigger fines.

The ransom will be much higher than any sum the criminals could have previously made through black market sales or ransomware decryption, but significantly lower than a GDPR fine. This could prompt companies to pay extortion rather than face high penalties. Malicious privileged users may be all too willing to take a bribe, especially when they know that their organisations have no visibility into what they are doing and that a massive pay day would never be revealed publicly.

Mark Coates, Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) vice president, and Ben Kennedy, UK and South Africa sales director at Dtex Systems, say that despite these increasing dangers, most companies do not have stringent systems for spotting insider threats.

“Maliciously fraudulent activity is increasing,” says Mr Coates. “Most organisations focus on monitoring movers, joiners and leavers. But there is a real insider threat from privileged users, who have the ‘keys to the kingdom’ and are savvy about not being spotted. If these individuals are open to bribery, the rewards can be huge.

“Enabling early visibility, with a fast signal into abnormal behaviour, can help to eliminate or reduce that insider threat. Dtex has a library of thousands of patterns of abnormal behaviour, scored according to potential threat level. We have built that database over 12 years to create a high-fidelity signal that minimises the number of false alerts.

“To be credible in this field, you need deep experience in understanding these behaviours, so you can benchmark them quickly. We have a wealth of knowledge and already know what ‘bad’ looks like, from monitoring against peer groups, within and across industries.”

Mr Kennedy says a high-fidelity, or high-accuracy, signal cannot only reduce false alerts, but also often tell whether an employee was being malicious, negligent or whether they have been compromised. In the case of the two bank employee case studies, the Dtex platform uncovered the abnormal behaviour and showed that it was malicious.

In another recent fraud case, involving a non-Dtex customer, the company was not able to prove malice and this has been driving demand for more sophisticated systems that can help prove it, says Mr Kennedy. This is because such proof can be pivotal in achieving a prosecution. In this case, a lawyer was working on behalf of a bank in an acquisition deal. Her husband obtained non-public information from her and used it for insider trading. He had clearly acted maliciously and was prosecuted.

But there was not enough data to show whether his wife’s behaviour in the incident was malicious, negligent, compromised or innocent. A more sophisticated system might have been able to prove this by providing a more detailed analysis of her behaviour.

Mr Kennedy says other legal firms have since purchased Dtex because this case highlighted the need for more evidence in such circumstances.

“They want an audit trail, so they would have a better chance of understanding what had happened in a situation like this,” he says. “It would put them in the best position to either exonerate or prosecute an employee in a similar situation.

“A forensically sound audit trail makes it possible to differentiate between malicious, compromised or negligent behaviour. Without the audit trail, it is easy for staff to claim negligence or [that they were unwittingly compromised].”

As more such cases come to light and the battle against insider fraud continues to intensify, the need for intelligent technology to counter it looks set to keep growing.

For more information please visit www2.dtexsystems.com/info