Top: Ahmad Alkhatib, Assurance business development director, BSI, Rhys Bush, Vice president, Europe, Middle East and Africa, Avetta, Rich Cooper, Principal, financial services, Fusion Risk Management

Bottom: Tim Janes, Chair Business Continuity Institute, Mary O’Connor, Chief risk officer KPMG UK, Jeroen Sourbron, Europe, Middle East and Africa sales director, Singlewire

Has the coronavirus crisis made companies take business continuity more seriously?

TJ: We’ve been surveying our members in the Business Continuity Institute over many months and it’s shown the crisis has certainly made senior executives pay attention. They now understand why they have been spending all this time preparing for business continuity.

AA: The feedback we’ve been getting from clients is that the pandemic has brought business continuity much more into focus. The additional point is the need to have a much broader, holistic approach to business continuity, looking at organisation-wide resilience, not only to survive disruption but, more importantly, the ability to respond and adapt to prosper. We did a COVID-19-centric pulse survey in April in the United States and the results were astonishing. Some of the top concerns were around supply chain resilience and we all know that the supply chain has been a key aspect of this pandemic.

JS: We’re in the mass-notifications business and we’ve definitely seen a shift in use-cases. Previously we were engaged with safety or business continuity person; now it seems to be more communications and human resources. Secondly, now that we see different phases – lockdown, reopening and even closing down again: a start-and-stop approach – it makes it a lot more important to execute on plans.

What lessons are there for supply chains?

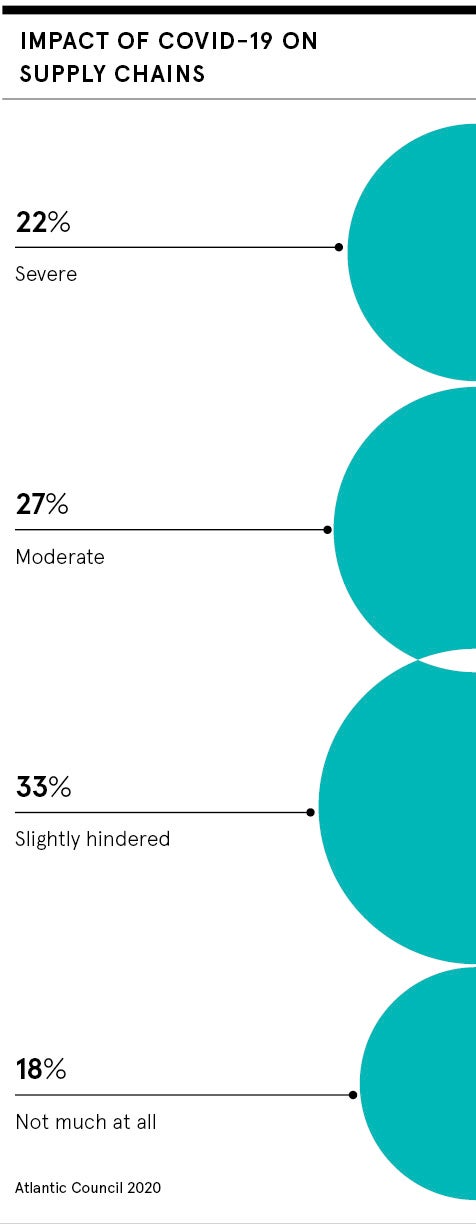

RB: There are big differences across the sectors. Some sectors that have traditionally been progressive in this area, such as pharmaceuticals and retail, are benefiting from the systems they have in place. But I spoke to the chief procurement officer of an international property company and she said her continuity plan was nowhere near ready for this. If they, as a large multinational conglomerate, weren’t ready, then it was somewhat unrealistic for them to expect all their supply chain would be. We see less risk appetite, which includes supply chains. During furlough lots of large companies didn’t have effective plans in place and had very little engagement with their supply chains. Now, as we return to work, there’s this rush to understand the financial and operational health of their suppliers. But they don’t always have the systems or the data to be able to achieve this.

RC: In the banking sector, they’ve had regulations in the United States and UK that you don’t migrate your risk by outsourcing. Therefore, supply chain resilience has been part of testing recovery capabilities at most banks for many years. What hasn’t been stress tested as much are tertiary parties and key parties such as other banks and credit bureaus that aren’t your traditional supplier. So there’s been an awakening that banking services are complex and involve a number of external sources. And the data has to be there. The companies that understand this are the ones which fared better. They were able to mitigate their risk and trace what would have an impact.

MO: But outside financial services, you don’t have the regulatory push which enables you to have that transparency. You’re only as strong as the weakest link in your chain, but it is difficult for companies to find that weak link. This is one of the things we’re doing, and seeing our clients doing, reaching out to third parties and asking how can I understand this better.

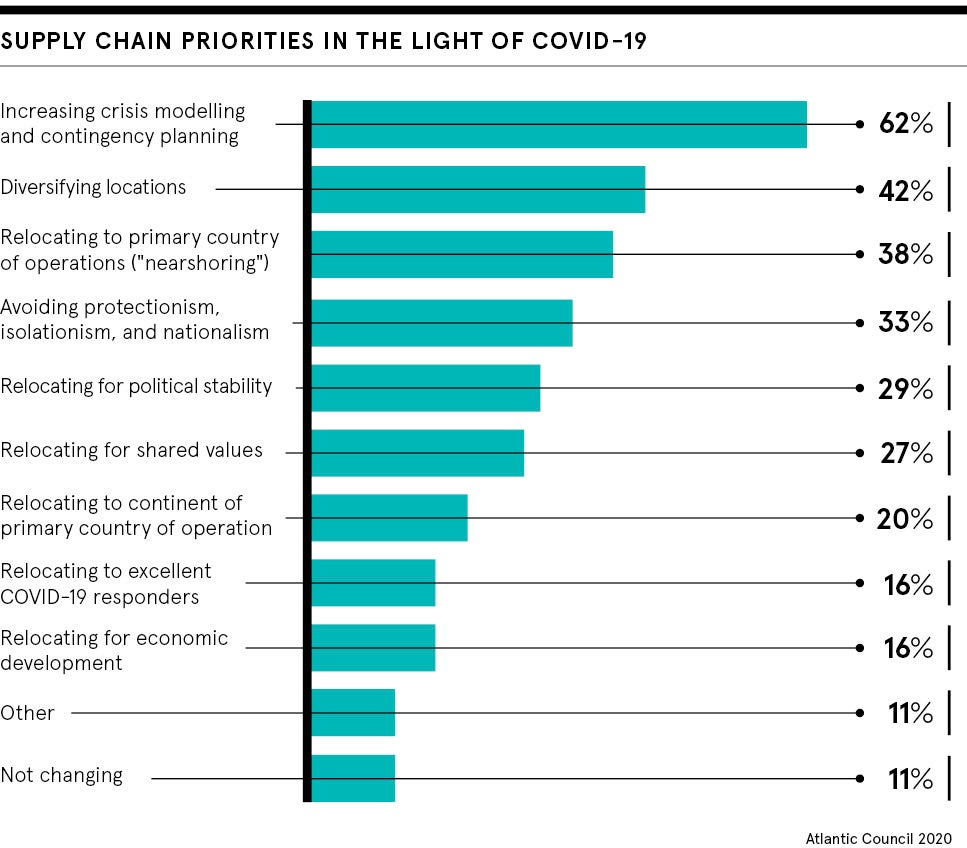

AA: In our pulse survey, most respondents rated their preparedness for supply chain disruption about average and around 50 per cent said they will make changes to the way they manage their supply chain. This clearly indicates the need to revisit the way we manage supply chain resilience, particularly with agility in mind. With complex supply chains increasingly spanning continents, there is a real challenge in getting the right level of visibility.

JS: I think it has put a focus on what we do around efficient notifications of disruptions with the use of new tools such as Microsoft Teams. The supply chain is becoming more and more important.

How does supply chain planning need to change?

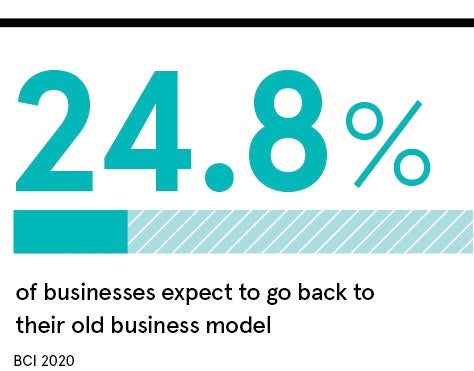

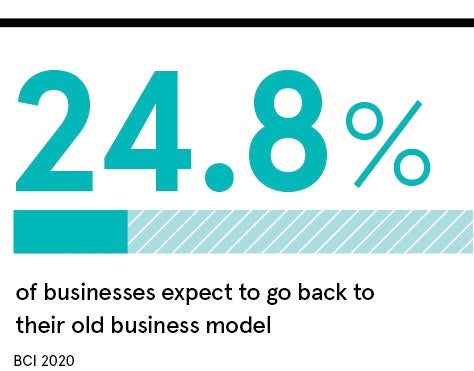

TJ: The organisations that have done supply chain continuity planning, and it tends to be the bigger ones, have tended to make assumptions about a single failure, such as a significant supplier or an area effect like an earthquake in Japan. None of them anticipated a situation like the pandemic that affected everyone at the same time. This obviously makes things more complicated, but it also changes the perception of what’s critical. When everybody is affected at the same time, what you define as “critical” can change quite radically.

RB: Until now a business continuity plan was a nice to have in supplier evaluation, rarely tested or audited. But for many blue chips, now it’s become a mandatory requirement for their highest-spend and strategic and key suppliers. However, there’s an issue here around engagement, education and taking all stakeholders along on this journey. They have a lot of small and medium-sized enterprises as suppliers and unless those companies are educated on what the future standards will be, it will be very hard for them to meet them.

It sounds like business continuity planning needs to become a lot more data driven?

RC: Traditional business continuity plans sat on a shelf after being approved by management. But now we’re seeing customers move to real time, looking into things like the performance of vendors – not missing the contracted service levels, but maybe beginning to degrade – to try and predict problems. Or looking back at weather events and other situations that have impacted business and trying to be more proactive, using not just historical data, but also forward-looking data. You need all that data in a digital format to analyse it.

JB: I’d agree with that. We’re seeing companies in all sectors have an appetite for new data, for better data—-and not just data for the sake of it. And as they become more data-driven they are challenging and evaluating their supply chains. They are also looking at existing historical data from different ways and leveraging that. For instance, high-risk sectors like transport have lots of safety and performance data which they have used to define who they choose as suppliers. We’re now helping them to look at that data from a different angle and thinking are these the companies we can rely on to adapt to new ways of working? It’s about leveraging existing data sources in the new environment.

Does business continuity planning have to start dealing with softer factors, more on the human side?

AA: Absolutely. There’s a lot more emphasis on the people aspect, including leadership and culture as well as vision and purpose. At times of volatility, we believe resilient leaders recognise the value of investing in a culture that instills a clear strategic purpose, alongside the tactical freedom of providing teams with the trust, support and opportunity to plan the optimum route.

RC: It’s important to remember that not every employee is the same. An example is at Fusion Risk Management we have a lot of millennials in our company who are not fortunate enough to have home offices. We also have a lot of employees who have a young family at home and don’t have daycare. So continuity planning is not just about the factory burning down, it’s about real people and ensuring they are able to be productive and are happy employees.

JS: Looking at our own organisation, we value a return to work as being both safe and productive. A conversation in the coffee corner could be more important than sitting at your desk for eight or ten hours. Not just HR but other parts of the organisation have to come together to make that kind of interaction possible.

MO: We’re still in a business continuity situation, but you now have to help people and support them over a longer time period, which means you need a bigger focus on wellness. We’ve done two pulse surveys and our results have been really positive because I think people have felt the organisation has adapted well. But it’s something we’ve had to learn as we’ve gone through because it wasn’t something we expected to be part of our business continuity planning.

Businesses typically have threat-based plans, such as a Brexit plan or a cyber plan. Does this need to change?

MO: I think there’s now a real understanding that plans need to work together. We realised this because when we switched to a heavy reliance on technology, with us handling such a lot of confidential data, we might end up with a cyber problem on top of our COVID problem. So now I think there’s a real understanding that plans are interlinked.

TJ: I don’t think anybody was planning for something of this size, scale and duration. The better organisations had what we would probably call an all-hazards plan that was flexible, could be quickly tuned to fit these very challenging circumstances and also, to Mary’s point, were collaborative. They allowed the organisations to work with staff and other affected organisations to adapt, based on a knowledge of what the priorities were for the organisation and the goals they were trying to achieve.

AA: Clearly, business continuity has to evolve in response to what we’re experiencing today. One way is strategic adaptability; we’ve seen many examples during COVID of organisations changing the scope of what they do, manufacturing things they haven’t made before or doing something entirely different. Leadership and culture are also vital; more resilient organisations were able to navigate this difficult environment successfully and instil this concept of agility and adaptability within their organisations. And clearly, governance is also important, such as in supply chains where there is an increased demand for more robust levels of governance, transparency and trust.

MO: I think the point about adapting is really important. You need to be outcome focused. You may not be able to deliver your product or service in quite the way you expected, but if you get the right outcome then that’s what matters. It’s about meeting the organisation’s needs, not about delivering in the same old way because that might not be possible in all cases.

RC: One of the things that has been historically problematic within organisations is they thought in silos, with one silo working on cyber-attack, another in facilities and another in HR. Look at the pandemic: it affects every part of the business and if the HR person is working in a silo away from the cyber-breach person, it’s not going to work. You’re all trying to protect the organisation, so why not work together?

But organisationally, isn’t it easier to unlock internal resources to solve a specific problem, such as a cyber-breach, than to create an all-problems business continuity plan?

TJ: I don’t think organisations suddenly are going to have one mega plan that everybody uses and covers everything. Some plans are inherently technical, such as an information security plan. What you change is the interaction, the collaboration. The plans should be written under one umbrella, share the same principles and be aiming for the same outcome.

MO: Yes, I think 2020 is the year all this is going to change. If you were planning for these simple scenarios, well they’re not simple and they’re all interrelated. We’re also going to have to manage in a business-interrupted world; we could go out of lockdown and then go back into lockdown for at least the next couple of months and probably for a couple of years. Companies that want to thrive in this new environment are going to be agile and master business continuity to bring these pieces together.

We may still be in the early days of this crisis, but are there clear lessons that already need to be learnt?

AA: Internally, we’ve realised we can be very agile and innovative in a short period of time. We’ve transformed our auditing and training to remote delivery by offering all our training courses remotely. We had projects we’d been working on for many months and when COVID came we found we could put them into full deployment within weeks. We want to take this agility with us moving forward. In terms of our clients, clearly a much broader and deeper understanding of continuity is needed. Organisations must look at their entire resilience profile and work with their partners, suppliers and stakeholders to build resilience over time.

JS: Traditional communication channels are completely challenged; you can see this by the fact we need to do this roundtable virtually. Organisations need the ability to reach out, provide customer experience and adapt. That’s why we’re constantly evolving our software. We have to go where our customers are going in terms of how they communicate and over what channels. There is also an issue in the global versus the local. We’ve seen organisations having global response mechanisms in place, but you also need to allow your local entity – it may be a country, it may be within a country – to make their own decisions, reacting immediately if things happen.

MO: One learning is that investment pays off. We had invested heavily in business continuity and it paid off within the first few weeks when we could pivot almost immediately to a full Teams-enabled environment with all our processes holding up. We also have to keep investing more in our people. We know we won’t always plan for the right business continuity problems, but if we have our people geared up and good processes, then we will thrive.

RC: Yes, investing in business continuity is a good investment, just like insurance is a good investment. But after the disaster, it is a little too late to buy a policy. The companies we see thriving now already understood how their business works, and the core services they provide to the marketplace, and are the ones that can maintain relationships with clients, while keeping employees happy. They have already broken down silos and have tied their plans back to those core services.

RB: Like Mary, we were well placed. We have a flexible platform and we adapted very early on; back in May we were already gathering new data about COVID and sending that out to clients. We’ve also explored new business models and many of these have worked. Having a culture where you’re encouraged to try new things, especially in such an unprecedented environment, has been hugely important for us.

TJ: At the Business Continuity Institute, we’ve been surveying our members every fortnight throughout the pandemic and there are perhaps two key success factors that have emerged. Firstly, a limited number of organisations keep their eyes open for events in the broader world, whether through official sources, such as the World Health Organization, listening to customers around the globe or even via social media. These organisations were able to pick up on early warnings of the coronavirus while it was still only in China and got a head start on what would eventually turn out to affect the whole globe. That in-house horizon scanning, providing information to senior management, gave them a huge advantage. Secondly, organisations that exercised their team regularly, and by that we mean at least annually, built up ingrained adaptability. It doesn’t mean practising for pandemics, it can be practising for anything. But when COVID came along, even though no one knew exactly what to do, it was the teams that were well rehearsed which could efficiently work through the problem and put a solution in place.

Has the coronavirus crisis made companies take business continuity more seriously?

TJ: We’ve been surveying our members in the Business Continuity Institute over many months and it’s shown the crisis has certainly made senior executives pay attention. They now understand why they have been spending all this time preparing for business continuity.

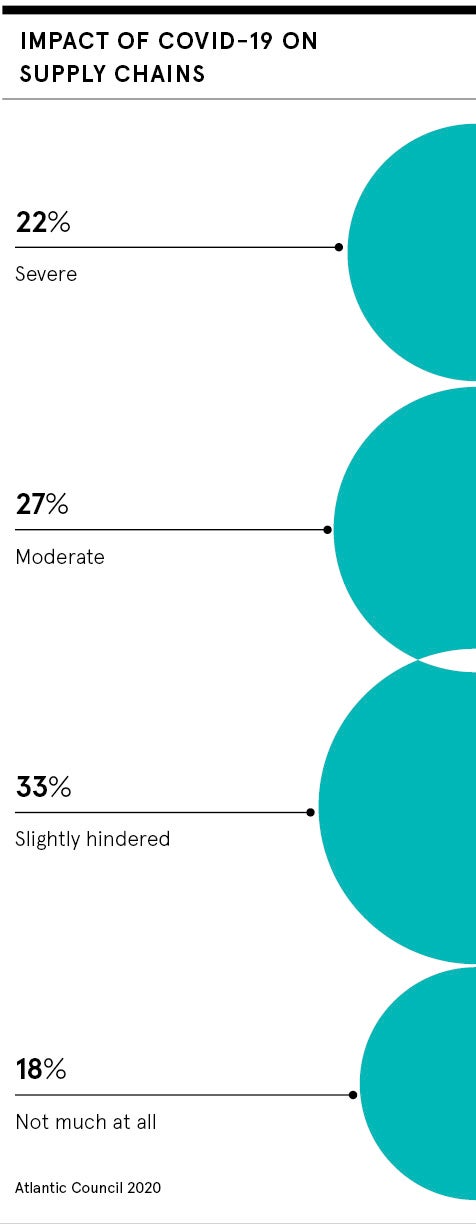

AA: The feedback we’ve been getting from clients is that the pandemic has brought business continuity much more into focus. The additional point is the need to have a much broader, holistic approach to business continuity, looking at organisation-wide resilience, not only to survive disruption but, more importantly, the ability to respond and adapt to prosper. We did a COVID-19-centric pulse survey in April in the United States and the results were astonishing. Some of the top concerns were around supply chain resilience and we all know that the supply chain has been a key aspect of this pandemic.

JS: We’re in the mass-notifications business and we’ve definitely seen a shift in use-cases. Previously we were engaged with safety or business continuity person; now it seems to be more communications and human resources. Secondly, now that we see different phases – lockdown, reopening and even closing down again: a start-and-stop approach – it makes it a lot more important to execute on plans.

What lessons are there for supply chains?

RB: There are big differences across the sectors. Some sectors that have traditionally been progressive in this area, such as pharmaceuticals and retail, are benefiting from the systems they have in place. But I spoke to the chief procurement officer of an international property company and she said her continuity plan was nowhere near ready for this. If they, as a large multinational conglomerate, weren’t ready, then it was somewhat unrealistic for them to expect all their supply chain would be. We see less risk appetite, which includes supply chains. During furlough lots of large companies didn’t have effective plans in place and had very little engagement with their supply chains. Now, as we return to work, there’s this rush to understand the financial and operational health of their suppliers. But they don’t always have the systems or the data to be able to achieve this.

RC: In the banking sector, they’ve had regulations in the United States and UK that you don’t migrate your risk by outsourcing. Therefore, supply chain resilience has been part of testing recovery capabilities at most banks for many years. What hasn’t been stress tested as much are tertiary parties and key parties such as other banks and credit bureaus that aren’t your traditional supplier. So there’s been an awakening that banking services are complex and involve a number of external sources. And the data has to be there. The companies that understand this are the ones which fared better. They were able to mitigate their risk and trace what would have an impact.

MO: But outside financial services, you don’t have the regulatory push which enables you to have that transparency. You’re only as strong as the weakest link in your chain, but it is difficult for companies to find that weak link. This is one of the things we’re doing, and seeing our clients doing, reaching out to third parties and asking how can I understand this better.

AA: In our pulse survey, most respondents rated their preparedness for supply chain disruption about average and around 50 per cent said they will make changes to the way they manage their supply chain. This clearly indicates the need to revisit the way we manage supply chain resilience, particularly with agility in mind. With complex supply chains increasingly spanning continents, there is a real challenge in getting the right level of visibility.

JS: I think it has put a focus on what we do around efficient notifications of disruptions with the use of new tools such as Microsoft Teams. The supply chain is becoming more and more important.

How does supply chain planning need to change?

TJ: The organisations that have done supply chain continuity planning, and it tends to be the bigger ones, have tended to make assumptions about a single failure, such as a significant supplier or an area effect like an earthquake in Japan. None of them anticipated a situation like the pandemic that affected everyone at the same time. This obviously makes things more complicated, but it also changes the perception of what’s critical. When everybody is affected at the same time, what you define as “critical” can change quite radically.

RB: Until now a business continuity plan was a nice to have in supplier evaluation, rarely tested or audited. But for many blue chips, now it’s become a mandatory requirement for their highest-spend and strategic and key suppliers. However, there’s an issue here around engagement, education and taking all stakeholders along on this journey. They have a lot of small and medium-sized enterprises as suppliers and unless those companies are educated on what the future standards will be, it will be very hard for them to meet them.

It sounds like business continuity planning needs to become a lot more data driven?

RC: Traditional business continuity plans sat on a shelf after being approved by management. But now we’re seeing customers move to real time, looking into things like the performance of vendors – not missing the contracted service levels, but maybe beginning to degrade – to try and predict problems. Or looking back at weather events and other situations that have impacted business and trying to be more proactive, using not just historical data, but also forward-looking data. You need all that data in a digital format to analyse it.

JB: I’d agree with that. We’re seeing companies in all sectors have an appetite for new data, for better data—-and not just data for the sake of it. And as they become more data-driven they are challenging and evaluating their supply chains. They are also looking at existing historical data from different ways and leveraging that. For instance, high-risk sectors like transport have lots of safety and performance data which they have used to define who they choose as suppliers. We’re now helping them to look at that data from a different angle and thinking are these the companies we can rely on to adapt to new ways of working? It’s about leveraging existing data sources in the new environment.

Does business continuity planning have to start dealing with softer factors, more on the human side?

AA: Absolutely. There’s a lot more emphasis on the people aspect, including leadership and culture as well as vision and purpose. At times of volatility, we believe resilient leaders recognise the value of investing in a culture that instills a clear strategic purpose, alongside the tactical freedom of providing teams with the trust, support and opportunity to plan the optimum route.

RC: It’s important to remember that not every employee is the same. An example is at Fusion Risk Management we have a lot of millennials in our company who are not fortunate enough to have home offices. We also have a lot of employees who have a young family at home and don’t have daycare. So continuity planning is not just about the factory burning down, it’s about real people and ensuring they are able to be productive and are happy employees.

JS: Looking at our own organisation, we value a return to work as being both safe and productive. A conversation in the coffee corner could be more important than sitting at your desk for eight or ten hours. Not just HR but other parts of the organisation have to come together to make that kind of interaction possible.

MO: We’re still in a business continuity situation, but you now have to help people and support them over a longer time period, which means you need a bigger focus on wellness. We’ve done two pulse surveys and our results have been really positive because I think people have felt the organisation has adapted well. But it’s something we’ve had to learn as we’ve gone through because it wasn’t something we expected to be part of our business continuity planning.

Businesses typically have threat-based plans, such as a Brexit plan or a cyber plan. Does this need to change?

MO: I think there’s now a real understanding that plans need to work together. We realised this because when we switched to a heavy reliance on technology, with us handling such a lot of confidential data, we might end up with a cyber problem on top of our COVID problem. So now I think there’s a real understanding that plans are interlinked.

TJ: I don’t think anybody was planning for something of this size, scale and duration. The better organisations had what we would probably call an all-hazards plan that was flexible, could be quickly tuned to fit these very challenging circumstances and also, to Mary’s point, were collaborative. They allowed the organisations to work with staff and other affected organisations to adapt, based on a knowledge of what the priorities were for the organisation and the goals they were trying to achieve.

AA: Clearly, business continuity has to evolve in response to what we’re experiencing today. One way is strategic adaptability; we’ve seen many examples during COVID of organisations changing the scope of what they do, manufacturing things they haven’t made before or doing something entirely different. Leadership and culture are also vital; more resilient organisations were able to navigate this difficult environment successfully and instil this concept of agility and adaptability within their organisations. And clearly, governance is also important, such as in supply chains where there is an increased demand for more robust levels of governance, transparency and trust.

MO: I think the point about adapting is really important. You need to be outcome focused. You may not be able to deliver your product or service in quite the way you expected, but if you get the right outcome then that’s what matters. It’s about meeting the organisation’s needs, not about delivering in the same old way because that might not be possible in all cases.

RC: One of the things that has been historically problematic within organisations is they thought in silos, with one silo working on cyber-attack, another in facilities and another in HR. Look at the pandemic: it affects every part of the business and if the HR person is working in a silo away from the cyber-breach person, it’s not going to work. You’re all trying to protect the organisation, so why not work together?

But organisationally, isn’t it easier to unlock internal resources to solve a specific problem, such as a cyber-breach, than to create an all-problems business continuity plan?

TJ: I don’t think organisations suddenly are going to have one mega plan that everybody uses and covers everything. Some plans are inherently technical, such as an information security plan. What you change is the interaction, the collaboration. The plans should be written under one umbrella, share the same principles and be aiming for the same outcome.

MO: Yes, I think 2020 is the year all this is going to change. If you were planning for these simple scenarios, well they’re not simple and they’re all interrelated. We’re also going to have to manage in a business-interrupted world; we could go out of lockdown and then go back into lockdown for at least the next couple of months and probably for a couple of years. Companies that want to thrive in this new environment are going to be agile and master business continuity to bring these pieces together.

We may still be in the early days of this crisis, but are there clear lessons that already need to be learnt?

AA: Internally, we’ve realised we can be very agile and innovative in a short period of time. We’ve transformed our auditing and training to remote delivery by offering all our training courses remotely. We had projects we’d been working on for many months and when COVID came we found we could put them into full deployment within weeks. We want to take this agility with us moving forward. In terms of our clients, clearly a much broader and deeper understanding of continuity is needed. Organisations must look at their entire resilience profile and work with their partners, suppliers and stakeholders to build resilience over time.

JS: Traditional communication channels are completely challenged; you can see this by the fact we need to do this roundtable virtually. Organisations need the ability to reach out, provide customer experience and adapt. That’s why we’re constantly evolving our software. We have to go where our customers are going in terms of how they communicate and over what channels. There is also an issue in the global versus the local. We’ve seen organisations having global response mechanisms in place, but you also need to allow your local entity – it may be a country, it may be within a country – to make their own decisions, reacting immediately if things happen.

Traditional communication channels are completely challenged; you can see this by the fact we need to do this roundtable virtually

MO: One learning is that investment pays off. We had invested heavily in business continuity and it paid off within the first few weeks when we could pivot almost immediately to a full Teams-enabled environment with all our processes holding up. We also have to keep investing more in our people. We know we won’t always plan for the right business continuity problems, but if we have our people geared up and good processes, then we will thrive.

RC: Yes, investing in business continuity is a good investment, just like insurance is a good investment. But after the disaster, it is a little too late to buy a policy. The companies we see thriving now already understood how their business works, and the core services they provide to the marketplace, and are the ones that can maintain relationships with clients, while keeping employees happy. They have already broken down silos and have tied their plans back to those core services.

RB: Like Mary, we were well placed. We have a flexible platform and we adapted very early on; back in May we were already gathering new data about COVID and sending that out to clients. We’ve also explored new business models and many of these have worked. Having a culture where you’re encouraged to try new things, especially in such an unprecedented environment, has been hugely important for us.

TJ: At the Business Continuity Institute, we’ve been surveying our members every fortnight throughout the pandemic and there are perhaps two key success factors that have emerged. Firstly, a limited number of organisations keep their eyes open for events in the broader world, whether through official sources, such as the World Health Organization, listening to customers around the globe or even via social media. These organisations were able to pick up on early warnings of the coronavirus while it was still only in China and got a head start on what would eventually turn out to affect the whole globe. That in-house horizon scanning, providing information to senior management, gave them a huge advantage. Secondly, organisations that exercised their team regularly, and by that we mean at least annually, built up ingrained adaptability. It doesn’t mean practising for pandemics, it can be practising for anything. But when COVID came along, even though no one knew exactly what to do, it was the teams that were well rehearsed which could efficiently work through the problem and put a solution in place.

Has the coronavirus crisis made companies take business continuity more seriously?

What lessons are there for supply chains?