Treating uncommon conditions, those that affect fewer than five people in ten thousand, represents one of the greatest challenges for medicine globally, today. The patient population is small and dispersed, there’s a high cost of bringing drugs to market, as well as a limited understanding of disease pathology.

“Finding patients can be difficult, sometimes with only a few per country, and it takes a lot of time to recruit for clinical trials, slowing development times for drugs. Small populations also create issues in generating data of sufficiently robust statistical standard,” explains Liz Gray, market access director for Ipsen UK and Ireland, who are focused on this sector.

Ms Gray continues, “Often we may not know much about the natural history of a disease, so you don’t always understand the likely diversity within the disease course. Drug development is also inherently unpredictable, and the problems are hugely increased with rare diseases where there is so little knowledge or data.”

Tackling rare diseases represents a new chapter in medicine and how the pharmaceutical business model functions. The standard way of working shifts, since developing financially viable therapies for such tiny markets is difficult.

Yet, is it fair that patients with a rare disease have less access to medicines?

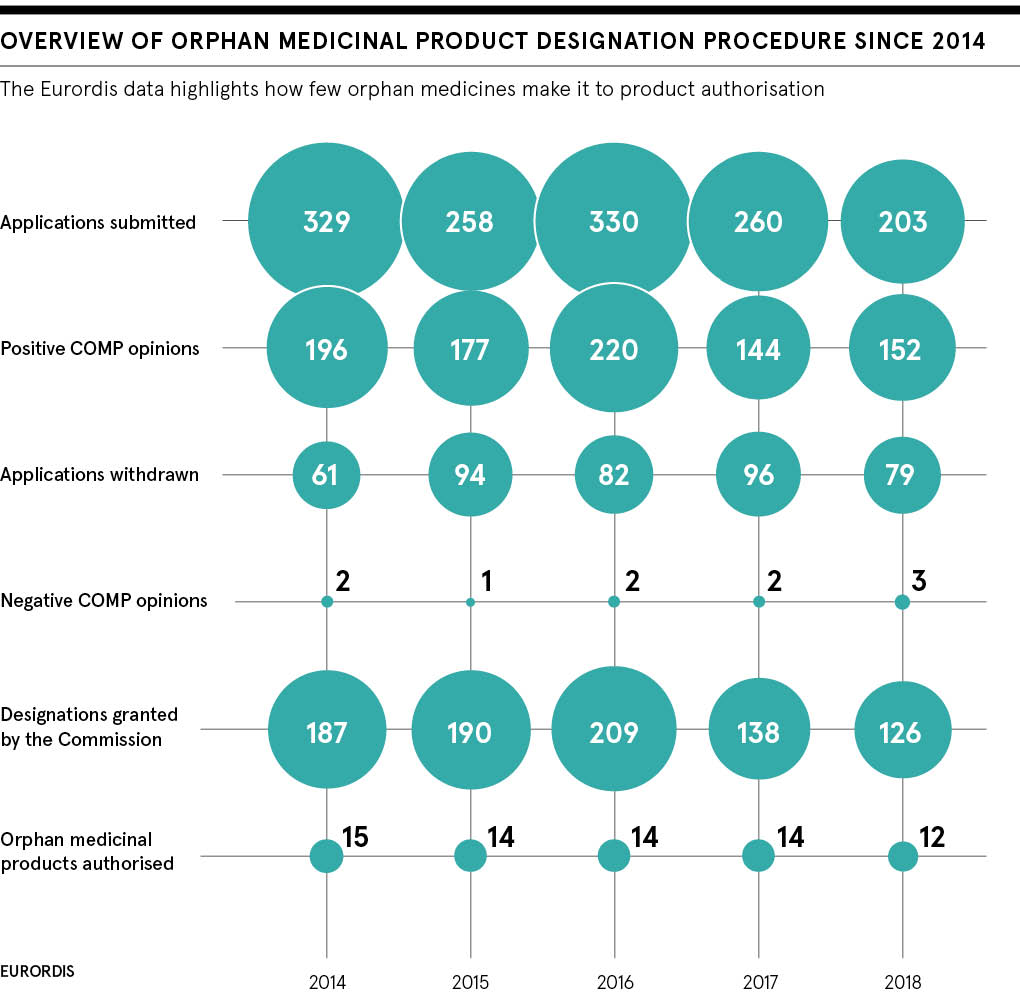

Yet there’s increasing interest amongst governments, health systems, doctors and patients to tackle uncommon conditions, many of which are genetic, debilitating and affect the young. Despite being termed “rare”, they collectively affect roughly three million people in the UK . It’s why the use of so-called orphan or novel drugs is on the rise.

“For patients, the biggest challenge is getting access to treatments with a high level of efficacy and a high probability of getting the benefit, with minimal side effects, there are simply too few that offer this in the current system,” states Eric Low, former chief executive of Myeloma UK.

“Pharmaceutical companies understandably want to make a fair return on their research and development, since they want the maximum return for their investors. However, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for companies to charge high prices for medicines that may only have marginal or uncertain benefits, even when there is huge unmet need,” explains Mr Low.

Certainly, there’s a trade-off between creating economic incentives to tackle rare diseases and the spiralling cost of treating growing numbers of ever-smaller patient populations.

How can pharmaceutical companies maintain the impetus for innovation if diseases are too small for the industry to see a return on their investment, or only at a price that’s unaffordable for healthcare systems? Yet, is it fair that patients with a rare disease have less access to medicines? It’s these issue that healthcare professionals are grappling with.

“We need to question why the cost of rare disease medicines is so high in the first place. This is an ethical question, as much as it is an economic question,” states Mr Low, who 20 years ago founded the only UK charity focused solely on multiple myeloma - a rare bone marrow cancer, for which there’s no cure.

The National Health Service in England is largely concerned with how it allocates scarce healthcare resources to derive maximum health benefits for the population as a whole. Their challenge is that the budget is capped and there is not enough money to pay for everything. Priorities have to be made. The treatment of rare diseases may not always be top of the list, if the data to support their use in uncertain, and prices very high.

“However, even if there was more money in the drugs budget, that doesn’t mean to say there should be a higher willingness or threshold to pay for treatments with marginal or uncertain benefits,” says Mr Low.

The move to an “outcome-based system” for drugs used to tackle rare diseases is one option, where pharmaceutical companies have to show that high prices actually reduce overall healthcare costs. Health providers may find that new drugs are more cost-effective in the long run for chronic, life-shortening rare diseases, in these cases, there may be a willingness to pay prices that allow corporations to make a profit.

“To stimulate research into new medicines in rare diseases, we have to ensure that investment and research, as well as development will be rightly rewarded where improvements in treatment options are found,” says Ms Gray, who works at Ipsen, which is a company with 90 years of experience in the pharmaceutical sector and a provider of rare disease therapeutics.

“We have to ensure that the system rewards those companies who consider thoughtfully their trial design. Conversely, as an industry, we have to be clear that it’s not reasonable to expect reward for mediocrity either. Doing the best for patients at every phase of a drug’s development should ensure success and, by association, reimbursement for our innovation.”

The system is evolving to address the problems. In England, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has a dedicated Highly Specialised Technology (HST) appraisal process for rare diseases. Scotland and Wales have similar systems. This is seeing a number of innovative reimbursement and pricing deals done with companies to bring orphan drugs to NHS patients.

“It is an improvement, but it’s not ideal. There are still rare diseases with all the attendant problems in data generation and disease understanding, they’re just not quite rare enough for HST . However, the process is at least recognition that there are nuances associated with the appraisal of medicines for rare diseases,” explains Ms Gray.

“While not yet perfect, we recognise that this process is still young and will evolve with time and understanding, including NICE’s latest consultation on the use of broader data and applied analytics. We hope that these mechanisms will generate fair outcomes for those with a rare disease and will encourage more innovation in drug development through reimbursement for products, which can demonstrate a benefit and cost effectiveness for patients,” states Ms Gray.

For more information please visit www.ipsen.com

This content is authored and sponsored by Ipsen Limited

Date of preparation: July 2019

ALL-UK-000910