SPONSORED BY Thought Machine

Paul Harrald, Head of Curve Credit

Charlotte Crosswell, Chief executive, Innovate Finance

Cristina Alba Ochoa, Chief financial officer, OakNorth

Andy Maguire, Chair of Thought Machine, former chief operating officer of HSBC

Paul Taylor, Chief executive, Thought Machine

What are the lessons from the pandemic so far?

CAO: What COVID-19 has made banks realise is lending decisions have typically been based on backward-looking, historical models. At OakNorth, we specialise in commercial lending and there was no model predicting what would happen to credit in a pandemic, especially to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). So banks are now having to start building forward-looking models.

CC: Obviously, we weren’t prepared to distribute funds to SMEs quickly enough. When the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme was put together, they didn’t have the best fintech brains around the table, which would have helped to get distribution going. The traditional banks can’t possibly supply all the demand for loans coming from SMEs in the next year, so it’s a time for fintech, in the broadest sense, to shine. We have an opportunity to pull together the best of technology, the best of finance, the best of alternative lending and really help the economic recovery.

The pandemic exposes that you need to be able to move quickly to service consumers

PT: Thought Machine is an infrastructure company, we don’t deal with consumers directly, but of course everything we do is built so the customer gets a better experience. But what does that mean in this particular context? Some traditional banks thought speed is something for the impatient millennial generation and that there’s nothing wrong with making people wait, but this isn’t the case. Unexpected events happen all the time and the pandemic exposes that you need to be able to move quickly to service consumers.

PH: Banks like DBS in Singapore didn’t just offer interesting types of loan forbearance; they provided an instant education programme about managing through a crisis and accessing their products and other peoples’. This shows banking and finance need not be purely technology and efficiency; it makes both human and financial sense to treat this thing as a relationship. A good example is credit scoring.

In my opinion, an event like COVID-19 should change no one’s credit score; it’s a random, macro-economic event, creditworthiness has not changed although affordability may have.

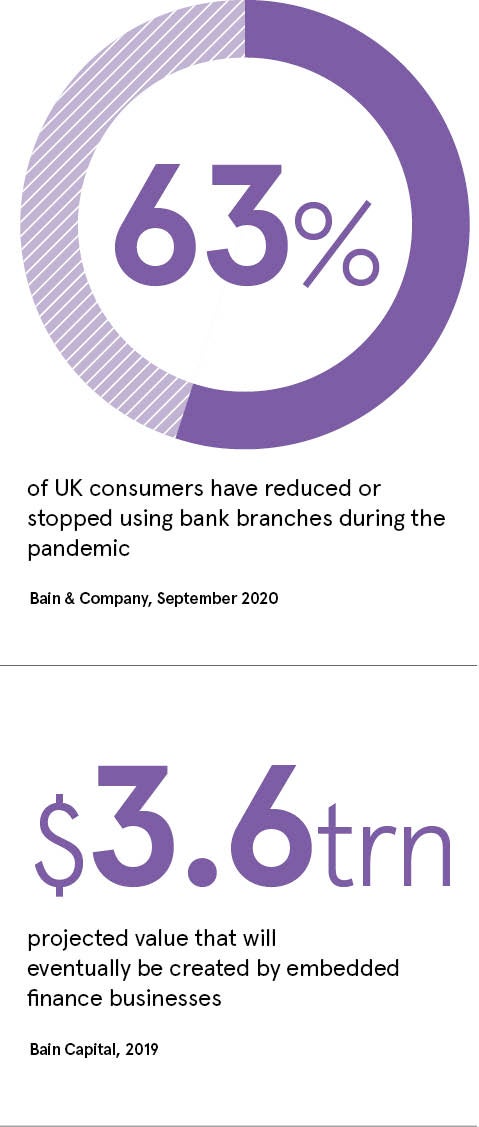

Is the shift to digital channels permanent?

AM: Digital is great for some things, but there are limitations and I think it will swing back; the question is how far. Look at business loans: if you upload your accounts and you don’t like the answer, ultimately you need to talk to a human. There’s a lot of issues around the resilience of our financial system; the

solutions need great technology, but also great people.

Apart from the move to digital, have other consumer behaviours changed?

CAO: We have seen an explosion in savings despite much lower rates. We’ve done some surveys with depositors, who say they don’t want to put their savings in shares or bonds that are perceived to be riskier, which indicates people have become more risk averse.

The solutions need great technology, but also great people

AM: It’s too soon to tell. Some people say we have become a nation of savers; I don’t think we have. We have been a nation unable to do retail shopping for a while.

PH: One of the most interesting effects has been a startling shift away from credit cards as a payment instrument towards debit cards. When consumers borrow, they are doing more with a Klarna or Curve Credit-style short-term instalment loan. This is a global phenomenon, I suspect driven by a sense of responsibility and a disaffection with the blurred distinction between paying and borrowing that can create persistent debt.

Andy, you had a long career at a global bank. How many of these changes are expected in a recession?

AM: We’ve seen some of these changes, sadly, before. You do see people become more financially conservative and paying more attention to stuff like debt. And then people forget pretty quickly, and then it all goes back to the way it used to be - at a macro level at least.

Banks have accelerated their internal digital processes over the last six months. Do they still need to partner with fintechs?

CC: Every financial institution we have been speaking to, not just banks but also asset managers and insurers, is expediting their digital transformation and I think that will continue quite aggressively. In the short term it will result in partnerships as it’s incredibly hard to bring that in at speed. But over time they will learn from that. They will move from partnerships, to investment, to acquisition, then building it themselves.

Banks will move from partnerships, to investment, to acquisition, then building it themselves

CAO: If you look at the traditional banks, their fully integrated systems are great for some things, but they are not agile. They can’t change their upstream and downstream processes as fast as someone like us. So we do believe partnerships are the future.

What are the unmet needs?

AM: There’s not a long list of services that don’t exist. Banking is not a recreational activity; it is a facilitator of the things people want to do in their life. And more or less, it serves them reasonably well, although it could be less clunky in all sorts of ways. It just needs to be as frictionless as possible and as human as it needs to be.

PT: I’m a recent joiner to the finance world, having worked for 20 years in artificial intelligence, which is really at the forefront of innovation. I think there are good ideas in banking, but I remain to be convinced there are going to be any fundamental shifts in the products offered to customers. But there are huge shifts in how well we can do it. When things are working well, the customer journey for most banks is fine, but when you get off that path, the level of pain can be astonishing.

CC: The unmet need is simplicity. Think how easy it is to change energy provider. Changing a mortgage provider, however, can take three months as the new provider goes through the paperwork and you prove who you are. Because of this complexity, people often re-fix with their current provider. We expect resistance from some financial institutions to change this, but it would be on my wish list for regulators.

AM: We have to be careful about romanticising simplification. Financial products are not commodities and they are not all the same. Under open banking, you can do price optimisation, but people choose and use products for different emotional reasons. Some people may buy a car with a loan even though they could pay for it with cash. It doesn’t make sense rationally, but it’s a mixture of emotions to do with big decisions in your life.

CAO: For SMEs, we believe there is a significant funding gap. We have quantified this globally, with external international banks, and we think worldwide it is $1.3 trillion to $1.5 trillion. It means many entrepreneurs are in growth mode, they need more than £1 million and there is no optimised debt financing that is not super expensive or super time consuming.

PH: I agree that people would like their financial lives to be simpler. There is potential frustration in trying to manage multiple relationships in a more competitive environment. Also, I think there is clearly an appetite for people to have slightly more racy personal savings. People quite like retail brokerages, they are very interested in things like cryptocurrencies, but the conduct regulators are of the view that this is perhaps not a thing for everybody.

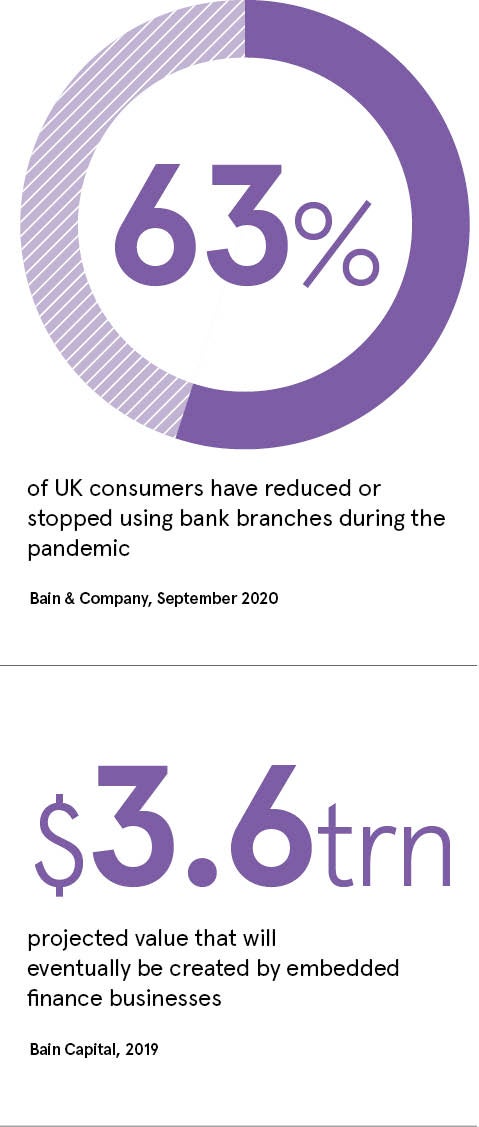

There is a lot of interest in so-called embedded finance, creating products or services that integrate financial with non-financial elements, often driven by data. A car dealer, for instance, could sell a car with not only financing but also insurance, which would reduce in price if the car’s sensors established you are a cautious driver. Is this a major opportunity?

PT: From the technology industry point of view, doing this well has proved to be incredibly hard for a variety of reasons. You need it all to integrate so it appears seamless. Also, companies generally want to own the whole product stack, just like Netflix wants to own its own stack from customer experience to creating movies. If we’re going to do it, we have to do it exceptionally well.

AM: Yes, we have to do it really well, but also securely, with the right protection, no fraud and no exploitation. How do you make it frictionless if you’re building in all these protections?

CC: We have to think about where Big Tech fits into this discussion and the data advantages they have already. For instance, people who have all this smart tech in their house, they are not thinking about the data which they are then providing on the back of that. This could have an impact on the insurance products you are offered in the future. We also need to understand how people are changing their buying behaviour, with millennials more likely to want to lease than buy, and think about the financial products they need.

CAO: I imagine it’s hard to get a good commercial agreement on an embedded finance partnership and it would be even harder if services are integrated. Whoever has the bigger access to the customer or to that service is best placed to do it and may try to take advantage of someone smaller.

Do embedded finance products suffer an inherent lack of transparency?

AM: As Cristina said, there is a risk that when you get two institutions together, they will talk about how big they can make the pie, then argue about the size of the slice they each get. It’s not necessarily about making things better for consumers.

PH: Once you start to embed things like credit, there is only a particular level of complexity that can be disclosed. A cynic like me might argue that one of the purposes of complexity is to make price comparisons deliberately difficult because companies don’t want to be compared solely on a single number. The other issue is these products blur the distinction between one part of your life and another, for instance blurring the distinction between deciding to buy something and financing it.

But isn’t it the blurring that generates the convenience?

PT: There is more subtlety than that. Having everything in one place generates confusion. If you look at the social media world, you might use one app for photo-sharing and another for video-sharing. It’s the way we work psychologically; it’s how we understand and partition. I think technology often works best when it reflects the objects in the real world rather than being necessarily super efficient.

PH: When people talk about simplification, what they are not saying is take a bunch of very different things and put a wrapper over them and somehow the world will be a less complicated place. Mixing your electricity bills with your pension would just add to complexity. Providing a wrapper of similar activities provides immense convenience and promotes competition. When finances become embedded, it may be difficult or inconvenient to switch, and it’s a shame when profits accrue because of this mere fact.

Under embedded finance, financial services become a hidden part of a product. What does this do to the value of financial brands?

PH: I suspect brands will continue to be very important, especially in the retail world, where people simply cannot do due diligence with every potential counterparty. Research suggests people are more open to handing their financial life over to different types of brands. The interesting question is whether they would be happy putting their money in the hands of a tech company. But they will still want to deal with a company with a brand presence. And that brand may well be a bank.

For more information please visit thoughtmachine.net

The pandemic exposes that you need to be able to move quickly to service consumers

The solutions need great technology, but also great people

Banks will move from partnerships, to investment, to acquisition, then building it themselves