When a 16-year-old Greta Thunberg stood before the United Nations general assembly in September 2019 and told them “all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth”, she skewered the heart of the current financial system.

Too often finance has been isolated from sustainability and social and environmental concerns, placing the needs of the present above those of future generations. The focus has solely been on the money, with little consideration of the problems such a single-minded approach might cause.

But mindsets are shifting. Climate change has exposed that some businesses, for example those that depend on burning fossil fuels to make their profits, can do more harm than good. Finance can no longer ignore “externalities”, however inconvenient they may be to the business of making money.

Beyond generating greenhouse-gas emissions, businesses are busy creating profits that can cause harm in many other ways too. Big companies have scoured the planet to find cheap resources, cheap energy and cheap labour to deliver cheap goods to us. Measured in financial terms the cost is low, but even if you haven’t watched Sir David Attenborough’s remarkable wildlife films, you will be increasingly aware of the many hidden costs of business to natural and social capital.

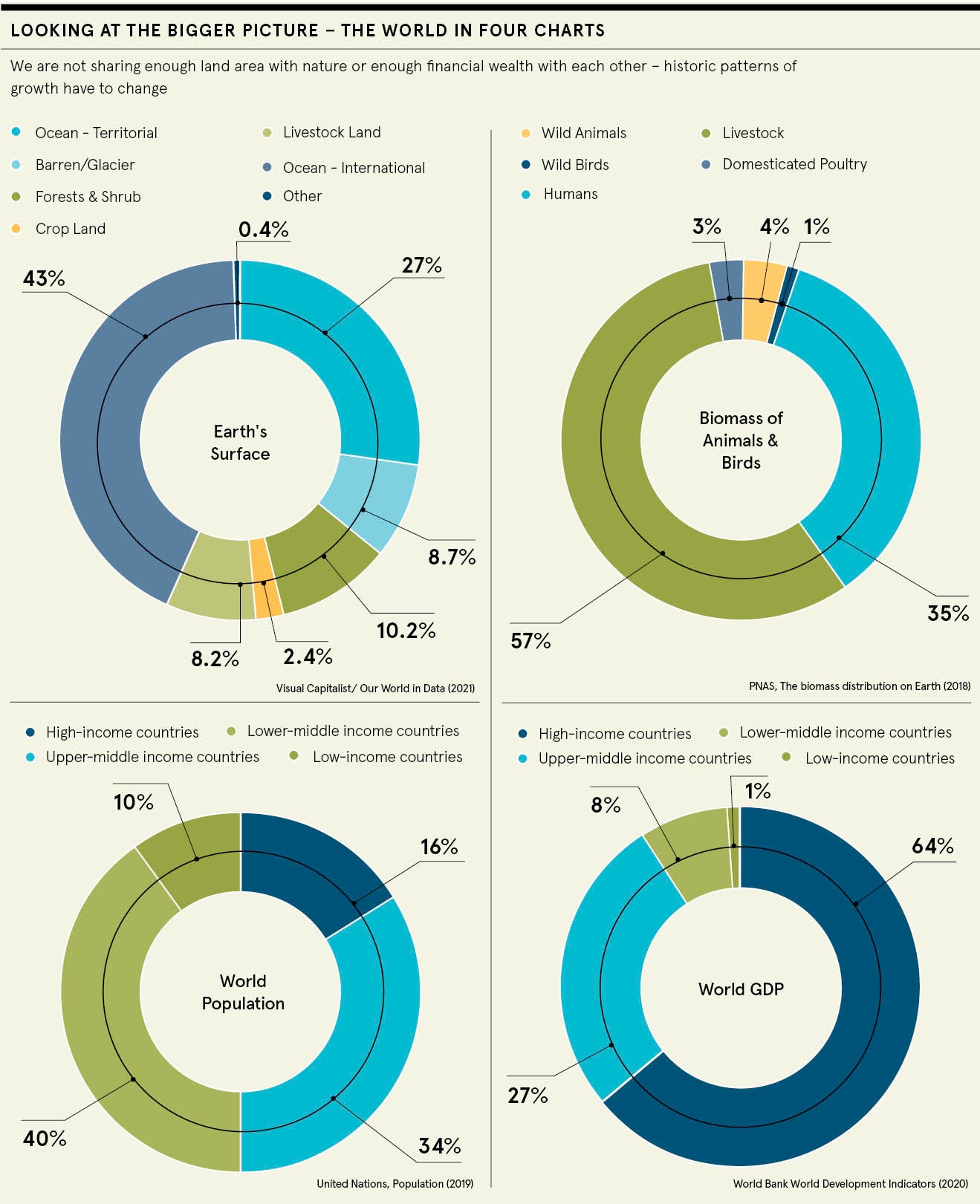

Population growth and economic progress have created too many activities that, while financially lucrative for their shareholders, are environmentally and socially destructive. And the scale of the natural capital loss is staggering: over the past 50 years, the human population has more than doubled, while the wild animal population has declined by 70 per cent.

And the breadth of financial gain has been remarkably narrow: in 2019, roughly two billion people suffered from moderate or severe levels of food insecurity. Such levels of environmental strain and social inequality are clearly unsustainable.

Not all of the blame can be placed on business; all of us are guilty of focusing on our own activities and not seeing the bigger picture. But if we are to solve these problems, many of us will need to recognise the system must change.

This is particularly true of those in the richer countries, with the most intense consumption, and the largest businesses organising and fostering that consumption. Those businesses and their investors must question whether the patterns of consumption that support their current profits can continue. By ignoring harmful environmental and social impacts they may be taking increasingly large financial risks.

Part of seeing the bigger picture is better measurement as what gets measured gets managed. At the moment, company accounts and investment management reports focus only on the money. But later this year, new sustainable financial disclosure regulations come into force in the European Union, with equivalent regulations expected in the UK. Proposed new accounting standards and more responsible audit practices are also on the cards.

These regulations will require investors and businesses to disclose the adverse impacts their investments have on the climate and the environment, as well as other sustainability issues such as social and employee matters, human rights and anti-corruption, or explain why they don’t consider them. That means financial returns will be viewed in a context beyond purely monetary value as the hidden environmental and social harms become increasingly apparent.

To better see the bigger picture, it also helps to stand back and consider the purpose of what you’re doing. “The purpose of business is to solve the problems of people and planet profitably, and not profit from causing problems” was the conclusion reached by the British Academy in their 2019 The Future of the Corporation programme.

An increasing number of large company management teams are pondering their purpose. They are listening to their employees, who want to work for a responsible and sustainable company, and their customers, who are increasingly favouring more ethical suppliers.

And they should be hearing more from their shareholders too. As the owners, it is incumbent on investors to steward their companies. In other words, to set the purpose of the business by directing the company management. This happens through voting on matters like the appointment of directors, incentive packages and major strategic changes, as well as engaging with the management team.

Wealth creation at society’s expense is likely to be ephemeral and sustainable companies are likely to make better investments

Too often this shareholder leadership obligation is treated passively and left for others to deal with. Responsibility may lie with the ultimate share owner or their agent, a fund manager. Sadly, too often it is the latter who has responsibility and the voting records of many fund management companies do not look good.

At Sarasin we have placed stewardship at the heart of our investment process for more than a decade. It is one of our core principles and it is how we believe we can secure tomorrow. Simply put, wealth creation at society’s expense is likely to be ephemeral and sustainable companies are likely to make better investments.

Investing to achieve a financial reward over the long term takes detailed work to look at the big picture to identify winning and losing investment themes that drive progress over time, to analyse financial value in the context of environmental and social capital costs, and to listen to our clients and reflect their views on sustainability in their investment strategies.

Encouraging corporate purpose and addressing “profits made from causing problems” does not mean the capitalist, profit-maximising “animal spirits” will be weakened. Instead, as costs and problems, which were previously hidden become better recognised, financial markets will begin to discount the long-term risk that the returns for many businesses could shrink, unless the externalities are costed and tackled.

This is already apparent as the move to net-zero carbon emissions gathers pace. The same will happen as actions start to be taken to reverse other big-picture impacts, such as biodiversity loss and inequality. Future investment success now depends on being ahead of the trend to integrate social and environmental costs.

Greta Thunberg is right, a narrow focus on money is unsustainable. By solving problems rather than causing them, and ensuring future generations are not compromised by the pursuit of profits today, investing can be sustainable. If we do that right, business, finance and investment can do more good than harm.

For more information please visit www.sarasinandpartners.com/think

Sponsored by

When a 16-year-old Greta Thunberg stood before the United Nations general assembly in September 2019 and told them “all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth”, she skewered the heart of the current financial system.

Too often finance has been isolated from sustainability and social and environmental concerns, placing the needs of the present above those of future generations. The focus has solely been on the money, with little consideration of the problems such a single-minded approach might cause.

But mindsets are shifting. Climate change has exposed that some businesses, for example those that depend on burning fossil fuels to make their profits, can do more harm than good. Finance can no longer ignore “externalities”, however inconvenient they may be to the business of making money.