Is the Queen dead? For a brief moment during the election campaign in early-December, quite a few people thought she might be. A WhatsApp message went viral, with a screen grab hitting Facebook and Twitter, seen and shared by hundreds of thousands of users. “Queen’s passed away this morning, heart attack, being announced 9.30am tomorrow…” began the would-be fateful message. Buckingham Palace was forced to issue a formal denial.

Fake news headlines accelerated by the weaponisation of social media have become all too common during election cycles and far more effective at shaping public opinion than the occasional viral death hoax on Twitter.

An investigation by the Oxford Internet Institute found evidence of organised social media manipulation campaigns, which have taken place in 70 countries, up from 48 in 2018. Governments and intelligence agencies have invested heavily in resources to prevent these campaigns from happening and to take down the “bad actors” behind them who wish to do harm to democracy and society at large.

Increasingly, these bad actors have a new target: the private sector. “We’re now seeing this behaviour extend beyond politics,” says Adam Hildreth, chief executive and founder of Crisp, which provides intelligence-led, real-time discovery of online content threatening a brand’s reputation. “Social media has unleashed a new range of capabilities for individuals and organisations with varying degrees of savvy to do harm to global brands.”

Top priority

Once negative publicity resulting from the acceleration of mis or disinformation on social media has reached the mainstream news cycle, the damage to brand reputation is already done. This can translate to an adverse impact on business, regulatory, operations and financial conditions. With brand reputation more publicly exposed, conversations about how to protect it have become a board-level priority.

It’s now become a matter of fiduciary responsibility and board-level compliance

In fact, brand reputation has increasingly found itself appearing on more and more company risk registers, specifically the management and mitigation of incorrect information spreading across social media and the wider web that can negatively influence consumer perception and purchasing decisions.

“It’s no longer optional,” says Mr Hildreth. “Look at any 10-K [annual report required by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

summarising a company’s financial performance] from today’s leading brands and you’ll see companies making the protection of their brand value from unverified or inaccurate content a top priority. It’s now become a matter of fiduciary responsibility and board-level compliance.”

What’s at stake?

The types of harmful content spreading online varies by industry. This year saw the rise of realistic “deepfakes,” which are computer-generated simulations of people perpetuated as photos, videos or voice messages. They are extraordinarily convincing. The Financial Times recently warned: “Fraudulent clips of business leaders could tank companies. False audio of central bankers could swing markets. Small businesses and individuals could face crippling reputational or financial risk.”

For example, a deepfake voice was used to scam a chief executive out of a six-figure sum. Earlier this year, the chief executive of an unnamed UK-based energy firm believed he was on the phone with his boss, the chief executive of the firm’s German parent company, when he followed orders to transfer €220,000 to the bank account of a Hungarian supplier.

The voice on the other end of the phone actually belonged to a fraudster using artificial intelligence voice technology to spoof the German chief executive. Rüdiger Kirsch of Euler Hermes Group SA, the firm’s insurance company, shared the information with The Wall Street Journal, which published the story.

In other cases, bad actors can create false content that is contrary to a company’s values or deliberately associate it with hate speech. Last year, Business Insider reported that coffee giant Starbucks fell victim to internet trolls who spread fake Starbucks coupons exclusively for black customers after the chain announced it would close stores for “racial bias education.”

The fake free coupons for customers of African-American heritage circulated on social media via the controversial website 4chan with hidden racial slurs and white-supremacist messages. This unfortunate attack by these bad actors spread quickly becoming mainstream news during an already difficult period for the popular global brand.

PepsiCo also encountered far-right groups during the 2016 US presidential election when it was reported by the Financial Times that they misquoted PepsiCo’s chief executive telling fans of Donald Trump to “take their business elsewhere.” Before the company could correct the disinformation, the financial and operational impact was clear as PepisCo’s stock price dropped 5.21 per cent.

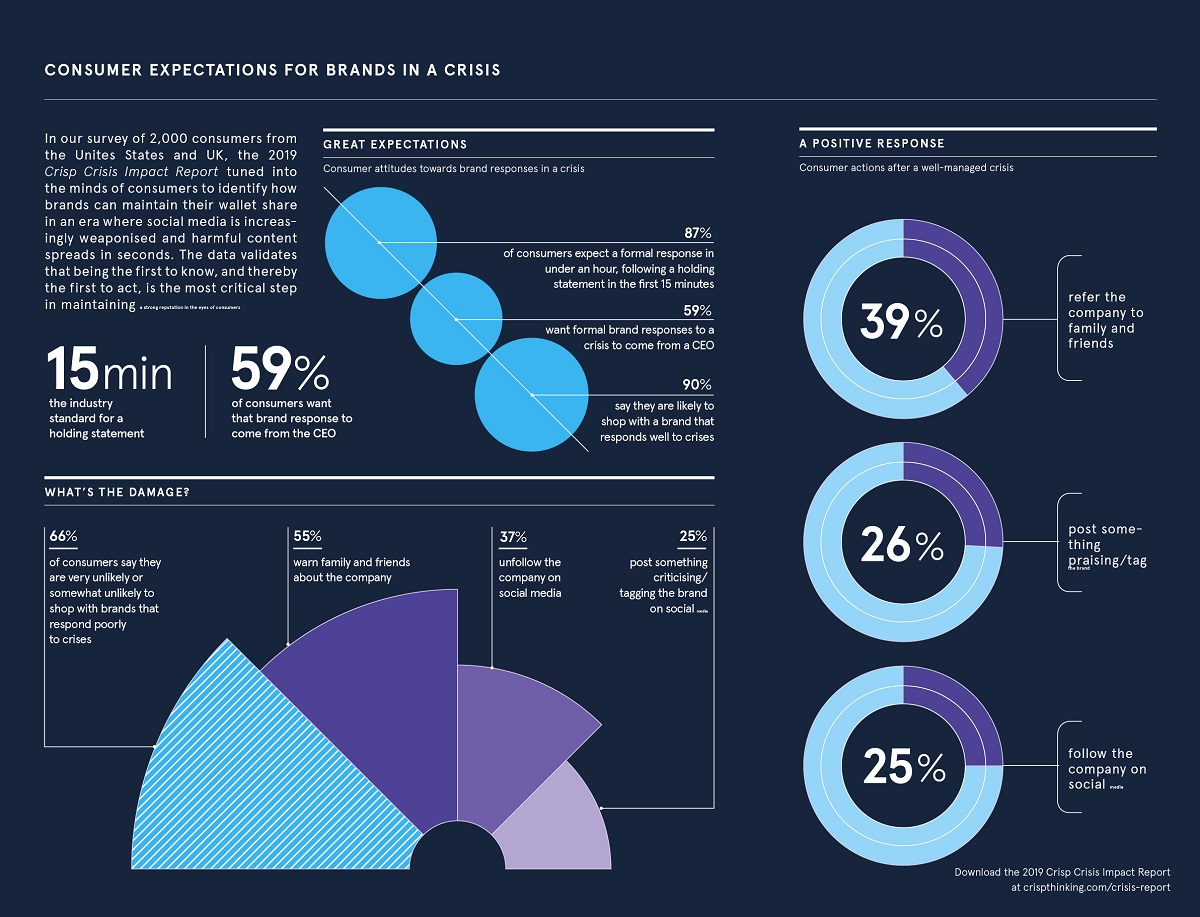

The first and most critical line of defence for brands is to gain knowledge as quickly as possible about misinformation or threats. The sooner the threat is detected, the sooner it can be addressed. Next step is acting upon the information. According to PR Daily, organisations have just 15 minutes to respond to a crisis situation with a holding statement. The majority of consumers expect that statement to be quickly followed by a response from the C-suite.

According to the Crisp 2019 Crisis Impact Report, which surveyed 2,000 consumers in America and the UK, 59 per cent want that brand response to come from the chief executive.

When these actions aren’t taken, or are handled poorly, consumers respond with their voices and their wallets. The same report cited that two thirds of consumers say they are very unlikely or somewhat unlikely to shop with brands that respond poorly to crises.

Are brands prepared?

Brands typically have tools and services to monitor the surface web, also called the visible web or indexed web, which is readily accessible to the general public via standard search engines.

While most people are familiar with Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn, more than three billion people globally are projected to be using social media in 2021, up from 2.8 billion in 2019, according to Statista, on hundreds of sites where social media can be weaponised and is not tracked by standard monitoring tools.

In mid-2019, the indexed web contained at least five billion web pages, according to WorldWideWebSize.com. The invisible web, also known as the deep or dark web, is projected to be many thousand times larger than the visible web. Unfortunately, the tools brands have relied on historically simply haven’t kept up with the evolution of social media and the wider web.

“By the time these threats to a brand’s reputation reach the surface web, it’s already too late,” says Mr Hildreth. “Brands need a sophisticated combination of artificial and human intelligence to actively manage the breadth and depth of online activity.”

Mr Hildreth and Crisp are no stranger to online harmful content. Crisp protects more than $3.6 trillion of its customers’ market capitalisation by providing intelligence-led, real-time discovery of online content that threatens their brand’s reputation.

Crisp combines artificial and human intelligence to deliver brand-specific, continually tuned social intelligence 24/7 with no false alarms. The company guarantees brands are always first to know, so they can be first to act.

“Unfortunately, it’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when,” says Mr Hildreth. “However, we find when brands are prepared with the right strategic intelligence to take the next best action for their business, they can thrive in this new era of social media weaponisation.”

For more information please visit crispthinking.com