Cancer life expectancy may have increased rapidly in the last few decades, but not for aggressive diseases such as some liver cancers and brain cancer. This high unmet medical need in seriously ill adults and children is being addressed by Midatech through nanotechnology, the use of materials that are 80,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair. The science is driving forward innovation by enabling doctors to target drugs at cancer cells and then deliver these medicines directly into tumours.

This cutting-edge approach is set to improve how patients tolerate those chemotherapy drugs, which are currently available, but are either highly toxic, difficult to infuse because of their insolubility or have limited efficacy. Employing nanotechnologies in different ways can overcome these challenges: systemic chemotherapy drugs can be targeted directly at a tumour when carried via gold nanoparticles fed into the bloodstream, while a technique called nanotech inclusion enables solubility and, therefore, the direct delivery of drugs via a catheter rather than orally. In both cases, not only are side effects minimised because there is less damage to healthy tissue, but also the efficacy of the treatment is increased as the drug is more accurately targeted at the tumour.

Another advantage of nanotechnology in cancer treatment is that it may enable therapies to move through tissue to reach diseased areas, such as tumour margins, and even cross the blood-brain barrier. In future, doctors may be able to target previously inaccessible tumours, such as highly aggressive and potentially fatal brain tumours.

We’re ensuring cancer treatment is effective by delivering it to the right place at the right time

According to Jim Phillips, chief executive for Midatech Pharma: “What we’re doing here in the UK with new technologies is the way forward. At the moment with currently approved cancer treatments, patients at best can hope for just a few extra months of survival with very poor quality of life. We’re ensuring cancer treatment is effective by delivering it to the right place at the right time. It’s both more effective and less debilitating, and that makes a huge difference, which is our goal.”

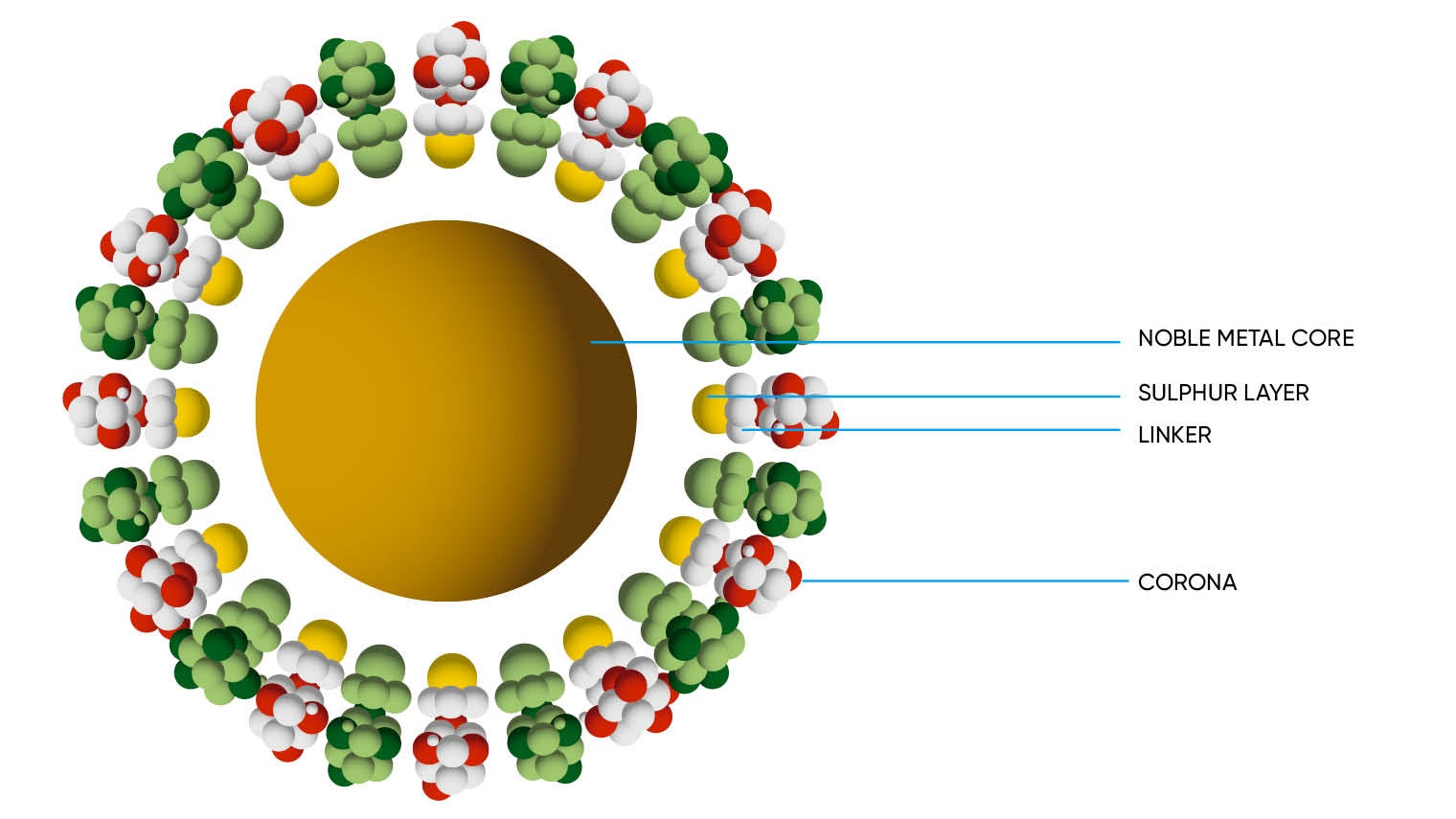

The key to Midatech’s success in the development of potentially lifesaving products is gold. As well as being safe because it is non-toxic, this precious metal is the ideal scaffold for the tiny particles used in the targeting and treatment of tumours. The form of gold nanoparticles the company has patented is manufactured in a state-of-the-art facility in Bilbao, Spain, which is believed to be the first plant of its kind licensed in Europe.

Dr Phillips says Midatech’s gold nanoparticles are adaptable and highly mobile, a considerable benefit when targeting hard-to-reach parts of the body such as the brain. “Gold nanoparticle technology has been researched in tremendous depth, but no one has yet commercialised the science and got it into the clinic,” he says. “What we’re talking about are particles less than two nanometres; each one contains 100 gold atoms. The size is crucial because it means the immune system isn’t disrupted, the therapies may access the traditionally hard-to-reach areas, and the nanoparticles can be safely excreted via the kidneys and liver.”

Regulation and licensing has a key role to play in the advancement of this area of research and development, and in making new treatments that do not come with harmful side effects a reality. Dr Phillips says that progress, for example, in Midatech’s child brain tumour research MTX110, which is about to enter phase-one clinical trials for children at sites in the UK, Europe and United States, has been made possible through a compassionate-use programme. Co-ordinated through European Union member states, these schemes help make products in development accessible to patients when satisfactory treatment options are non-existent.

While regulators are generally supportive of novel approaches in the field of orphan cancers, Dr Phillips says there is always room for improvement. “Some regulators are like minded, others are tricky and want you to jump through more hoops, and others blow hot and cold,” he adds. “All the approvals [in this area] have been for palliative support because there haven’t been the breakthroughs. Regulators are looking for evidence-based research from formal clinical studies, which is a challenge because the number of patients available to take part in trials for rarer cancers is limited.

“Typically, authorisation can take years, but our hope is that the path to this can be accelerated with approvals based on evidence from a single pivotal trial. The existence of special schemes also boosts the chance for patients with life-limiting conditions to get access.”

With Britain set to withdraw from the EU in March 2019, Dr Phillips also believes it is vital the UK retains its status as a leading global hub for the life sciences industry. “It’s vital for high-tech and innovative industry to have clear access to the European market so that products are approved as before. At the moment this isn’t guaranteed because of a lack of clarity over what the UK’s position is, which makes planning for the future a challenge. Our ideal as a company is that the UK continues as a member of the European Medicines Agency, and we go to them for product evaluation and authorisation.”

He says collaboration is important in the growth of knowledge and competence in what is a fast-developing but relatively nascent technology. Only a handful of centres in the UK and United States currently have the expertise, and Midatech is not at the point yet to deliver products through the NHS, although several are already in late-stage development. Dr Phillips says the ability to treat rare and orphan cancers is a niche but growing skillset and Midatech is “working and collaborating with our experts and partners”, including with a number of universities and pharmaceutical companies, both major and speciality ones.

The message from Dr Phillips is simple. He believes that as long as there is the right support from regulators and continued partnership among those with expertise in this area then effective and tolerable first-line treatments will become a reality. For cancer patients whose choices are either limited or non-existent, that would be an outcome worth more than its weight in gold.

Cancer life expectancy may have increased rapidly in the last few decades, but not for aggressive diseases such as some liver cancers and brain cancer. This high unmet medical need in seriously ill adults and children is being addressed by Midatech through nanotechnology, the use of materials that are 80,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair. The science is driving forward innovation by enabling doctors to target drugs at cancer cells and then deliver these medicines directly into tumours.

This cutting-edge approach is set to improve how patients tolerate those chemotherapy drugs, which are currently available, but are either highly toxic, difficult to infuse because of their insolubility or have limited efficacy. Employing nanotechnologies in different ways can overcome these challenges: systemic chemotherapy drugs can be targeted directly at a tumour when carried via gold nanoparticles fed into the bloodstream, while a technique called nanotech inclusion enables solubility and, therefore, the direct delivery of drugs via a catheter rather than orally. In both cases, not only are side effects minimised because there is less damage to healthy tissue, but also the efficacy of the treatment is increased as the drug is more accurately targeted at the tumour.

Another advantage of nanotechnology in cancer treatment is that it may enable therapies to move through tissue to reach diseased areas, such as tumour margins, and even cross the blood-brain barrier. In future, doctors may be able to target previously inaccessible tumours, such as highly aggressive and potentially fatal brain tumours.

According to Jim Phillips, chief executive for Midatech Pharma: “What we’re doing here in the UK with new technologies is the way forward. At the moment with currently approved cancer treatments, patients at best can hope for just a few extra months of survival with very poor quality of life. We’re ensuring cancer treatment is effective by delivering it to the right place at the right time. It’s both more effective and less debilitating, and that makes a huge difference, which is our goal.”