Expanding amounts of freely available, open access patient data can now be used by clinicians and the pharma industry to hone drug development and identify biomarkers that can help identify which drugs will work best to treat a patient’s cancer, based on the tumour’s genetic profile.

Expanding amounts of freely available, open access patient data can now be used by clinicians and the pharma industry to hone drug development and identify biomarkers that can help identify which drugs will work best to treat a patient’s cancer, based on the tumour’s genetic profile.

The pharmaceutical picture is exciting and personalised or precision medicine is increasingly expected to revolutionise cancer treatment, but its success depends on parallel development in companion diagnostics.

In short, this field involves bio-analytical methods designed to assess whether a patient will respond favourably to a specific medical treatment or not and the science in this field is advancing rapidly.

It has changed the shape of drug development, creating an ecosystem with many stakeholders. Whereas before a pharma company could develop a drug in relative isolation, they now need to collaborate with diagnostics manufacturers, testing laboratories, health informatics, commissioners and regulators to provide a viable, safe and cost-effective treatment pathway.

In addition, the role of the patient is of course paramount and a large-scale data-gathering exercise is required to establish the patient populations that will benefit from therapies. It is likely industry will need the help of healthcare systems to map patient populations, and get a better sense of what will work on whom and for which conditions.

Diagnostics in the NHS

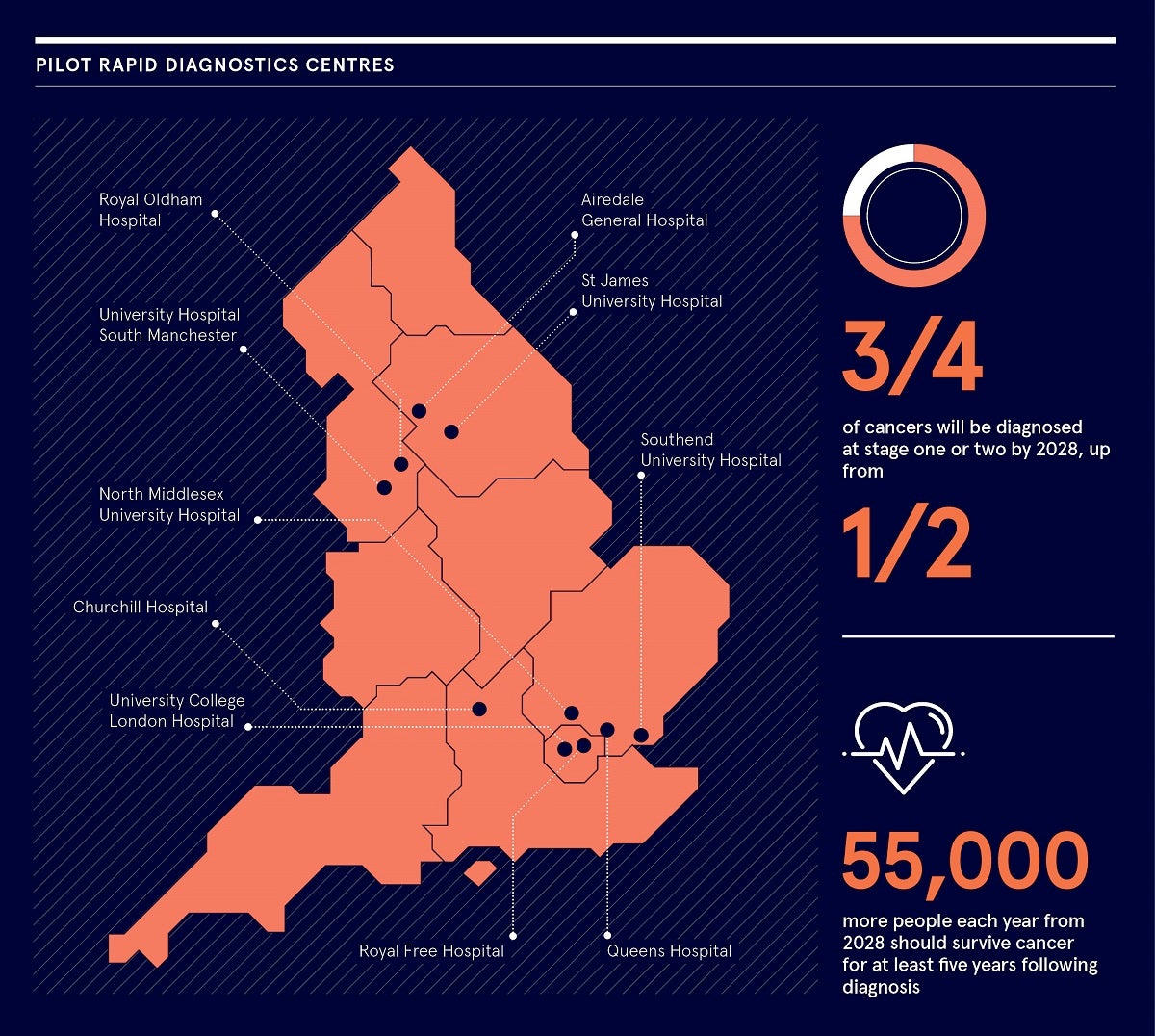

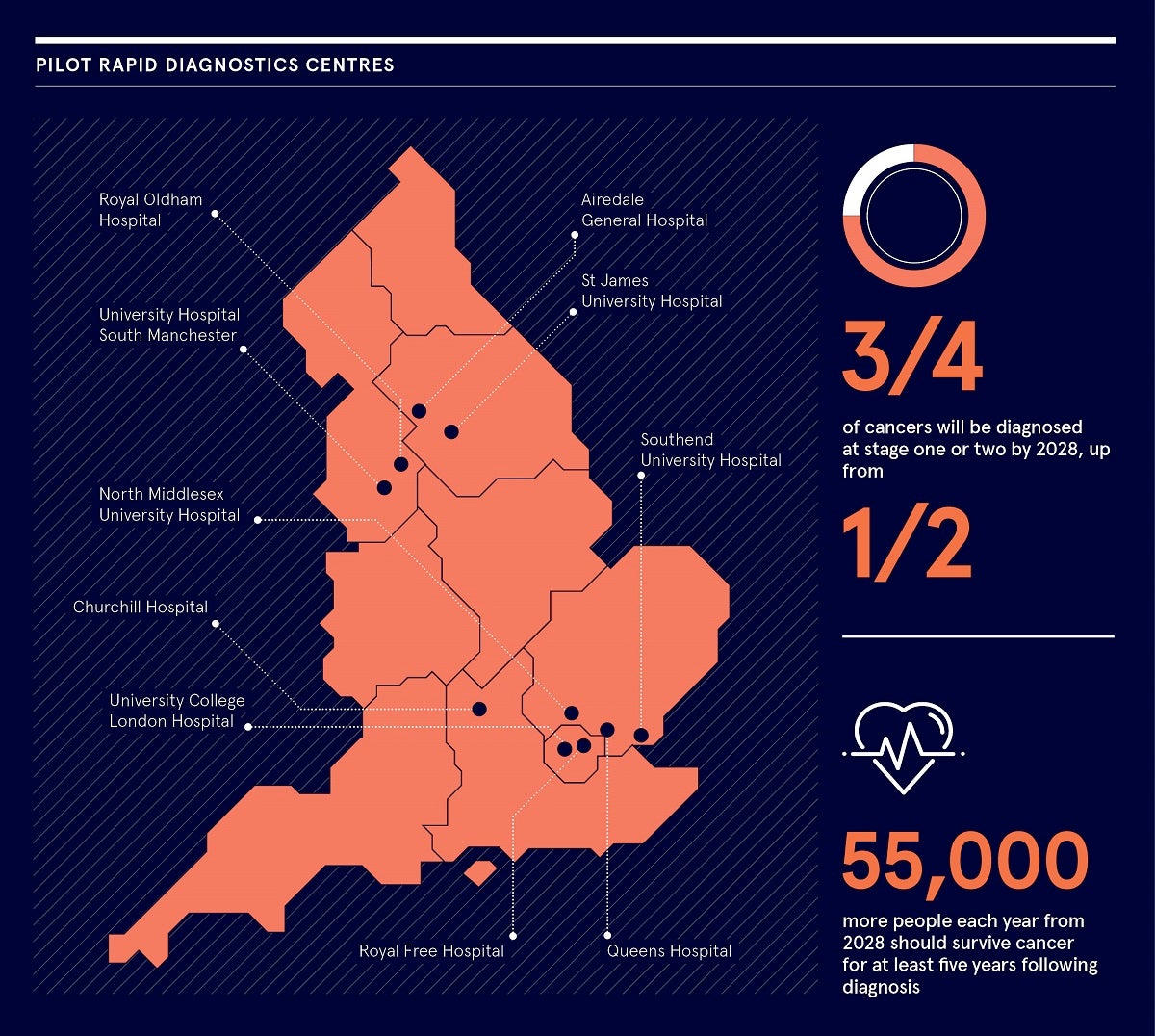

With this as the background, cancer diagnosis has been put front and centre by the UK government and in England the 2019 NHS Long-Term Plan has set in place two ambitious targets.

By 2028, the proportion of cancers diagnosed at stages one and two should rise from around half to three quarters of cancer patients. Then, from 2028, 55 000 more people each year should survive their cancer for at least five years following diagnosis.

These two targets are intended to reinforce each other as we know that many cancers become more survivable if captured early, at stages one and two. And to capture them early, we need early diagnosis.

To make this a reality, the long-term plan has put in place two key pieces of infrastructure. The first is cancer alliances; groups of cancer clinicians that will drive the development of cancer pathways at a local level. The second is the emergence of rapid diagnostics centres.

Currently existing in pilot form, rapid diagnostics centres are multi-disciplinary and can cover much of the data-gathering work.

They provide a single point of access to a diagnostic pathway for all patients with symptoms that could indicate cancer, and a personalised, accurate and timely diagnosis of patients’ symptoms. They combine all existing diagnostic provision, and use networked expertise and information.

Success will depend on corralling many disparate resources in the NHS, including GPs, who form a big part of this as, supported by the local alliance’s clinical network, they will refer patients with suspected symptoms to rapid diagnostics centres. These can be non-specific. For example, lung cancer at an early stage can resemble a common cold, and the greater provision provided by rapid diagnostics centres and their networks can help pick this up.

Another benefit is, if the patient does not have cancer, but another condition, they can be put on the right pathway by the multi-disciplinary team.

Rapid diagnostics centres are currently clustered around the vanguard areas of London and Manchester, but the idea is for the cancer alliances to take this forward so all areas of England will be covered by 2023.

This is especially important as speed of diagnosis and cancer survival vary widely by healthcare community. Access to diagnostics services and therapies, and the outcomes from them, can depend on where you live.

Research by Wilmington Healthcare has shown that lung cancer is a particularly variable type. Most diagnoses are at stage four, by which stage the cancer is much less survivable. How likely a patient is to come forward before that is affected by a wide variety of factors, such as an area’s deprivation, population and quality of screening services.

The use of novel treatment also varies widely and Wilmington Healthcare’s specialist share data service has highlighted wide discrepancies in what is prescribed, with a significant trust-by-trust range for drug combinations, particularly for rarer cancers, such as chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and multiple myeloma.

This can have the effect of patients being put on a drug that is first line in that healthcare community, but will not necessarily work on them. If NHS diagnostics is enabled in the way the government wants, and is matched with the rollout of precision medicine, this will begin to happen less, with patients more likely to be given an effective therapy.

Way forward

Rollout of high-quality and fast diagnostic services across the country, and the concomitant development of personalised medicine with companion diagnostics, could be transformative, but it will also require close and co-operative working between the NHS, and the pharma and diagnostics industries.

If they can get this right, progress against the disease could be considerable and, if the long-term plan’s targets are met, we can consider this a great leap forward. As the industry has suggested, while cancer may lead the way in this process, there is scope for personalised medicine

and companion diagnostics to transform the way we treat other conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, arthritis and Alzheimer’s disease, and even mental health conditions, such as depression.

Discover how we can help you identify your NHS customers and engage them more effectively by tailoring your value proposition to their localised needs.

E: info@wilmingtonhealthcare.com

W: wilmingtonhealthcare.com

T: 01268 495600

Diagnostics in the NHS