Higher education has been going through a busy period of reform and change. We’ve seen tuition fees increase dramatically, but also a host of incentives to try and improve the experience of university for students have been introduced. There has been a focus on improving teaching quality and employability outcomes, and at the same time students have been reframed as consumers with rights.

This academic year universities are gearing up to introduce reforms in 2017 such as the Teaching Excellence Framework, a new measurement of the quality of academic teaching. In addition, they will need to respond to other policies brought about by new legislation in the form of the Higher Education and Research Bill.

Also, after campaigning strongly to remain in the European Union, the sector has the vote for Brexit to be concerned about. Earlier this month, Universities UK called for clarity from the government on what kind of settlement it will draw up for students coming from the EU. They certainly don’t want to see a drop in EU applicants.

Strength of universities

What will happen next? It’s definitely a time of change and uncertainty for the sector, but observers are cautiously optimistic that the strength of British universities will hold up amid the commotion.

A sign of that strength is how popular going to university remains despite the higher costs. Tuition fees have existed in some form for many years, but it was the Coalition government that made student fees the main source of university funding, trebling them to £9,000 a year from 2012 and cutting back on grants from central government.

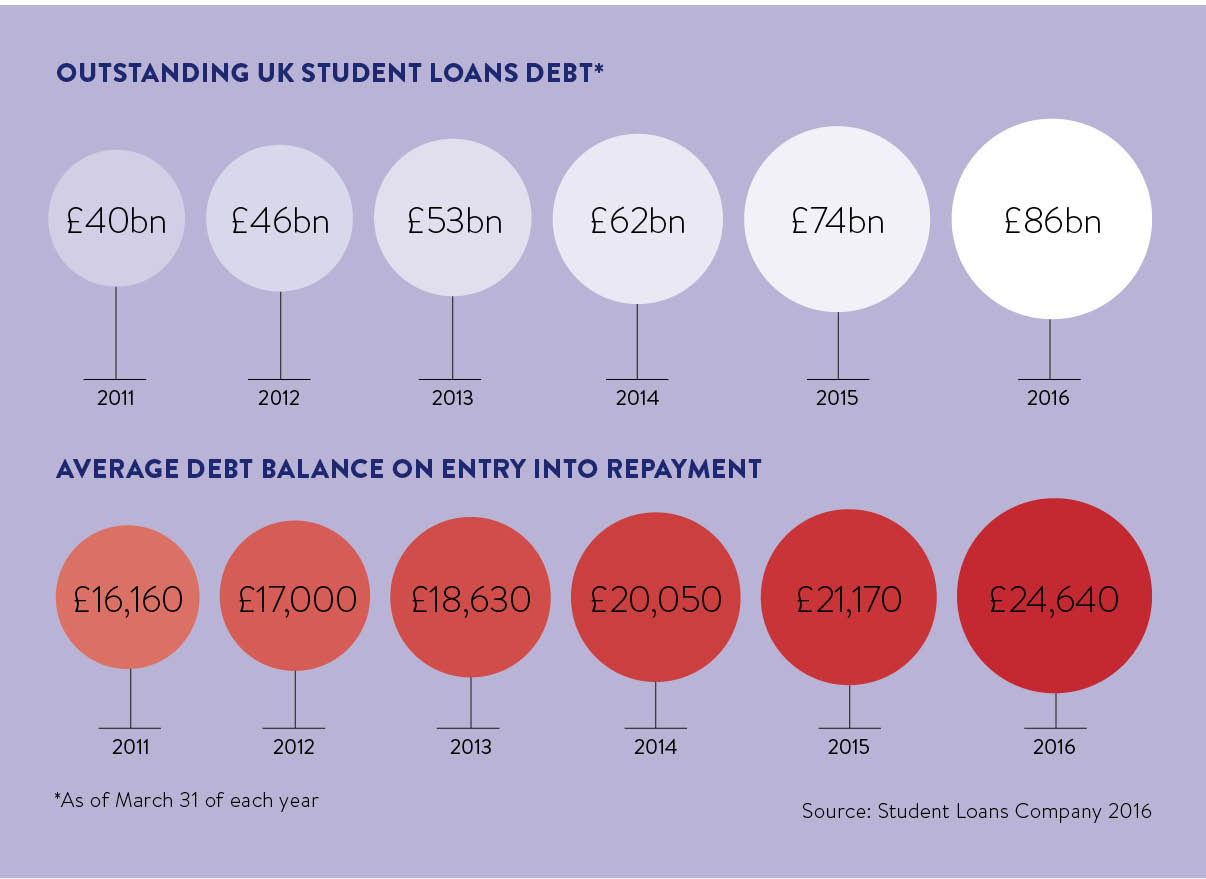

Four years on, fees are still controversial. A report by the Sutton Trust in April found UK graduates incur the most university debt in the English-speaking world and there are concerns that the graduate job market simply isn’t able to provide enough well-paid jobs.

But despite the gloomy predictions, fees haven’t dented the number of school-leavers going to university. Instead, universities have spent the last few years expanding their campuses and enrolling more students, especially since the student numbers cap was lifted in 2014.

A record 424,000 students were awarded places on A-level results day this August, up 3 per cent on last year. Also the Office for Fair Access, which monitors how successful institutions are at attracting students from low-income families, found there was a 7 per cent increase in the number of students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds achieving places. Although the most advantaged young people are still 2.5 times more likely to go.

Consumer rights

The plan is that in return for paying their higher fees, students will demand more from their higher education and drive up quality. Students have been given consumer rights and the government plans to create a new Office for Students which will regulate the sector, take action on complaints and publish university performance data.

Already prospective students are eyeing up the earnings of university alumni to judge whether that university or that course is worth it and this more shrewd approach is set to continue.

“Turning the student into a consumer has been a mixed blessing,” says Mike Boxall, an expert in higher education for PA Consulting. “In some ways it has been really successful. In the space of just three years it is clear that universities have been incentivised to look after student needs more carefully, far more so than previously.

“At the same time we are slightly in danger of over-commodifying education, seeing it only in instrumental terms. Students are being encouraged to view university only as a place to improve their earnings later.”

Universities are even giving out gifts to attract students with good grades. “You hear of universities offering season tickets for the football along with their unconditional offers rather than talking about the quality of the education they provide. That seems out of balance,” says Mr Boxall.

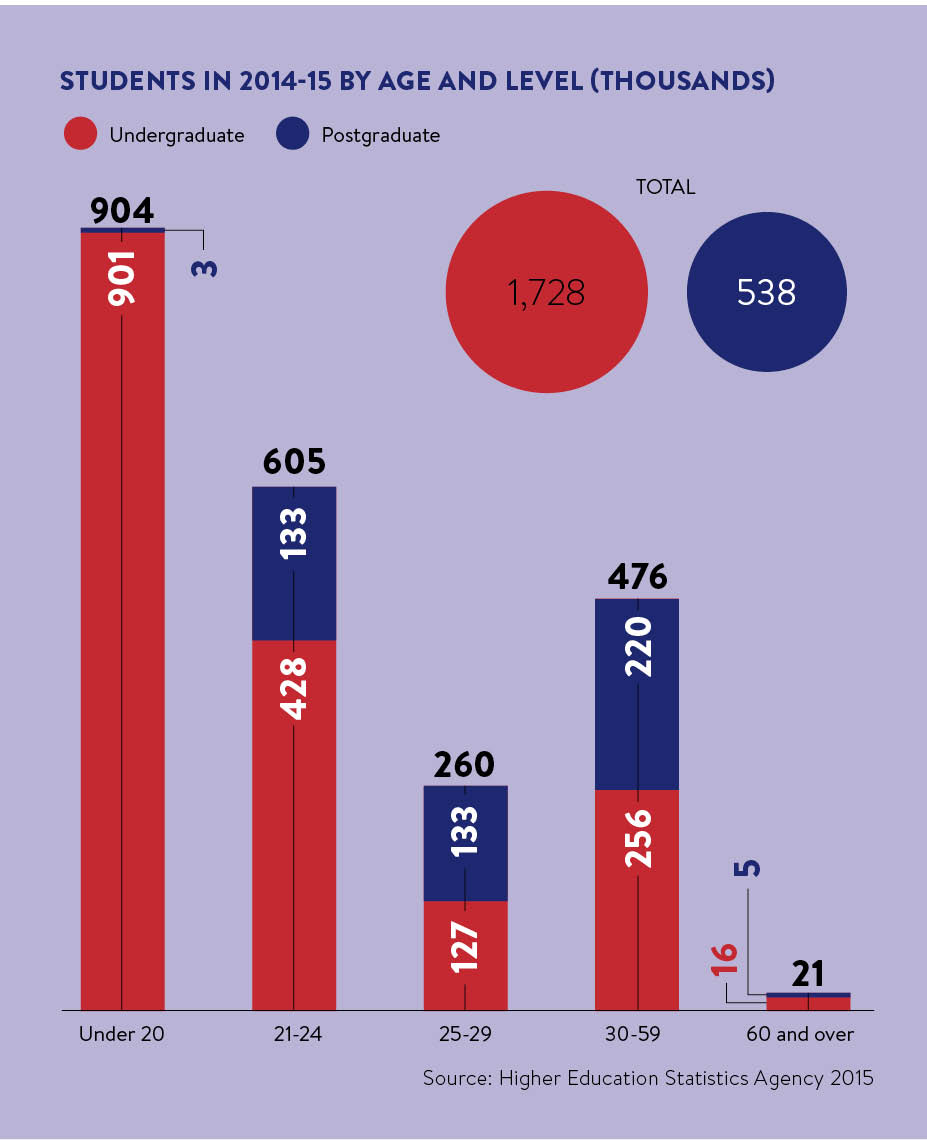

Although school-leavers are still choosing to go to university to do a full-time course, the same is not the case for part-time students, who are usually older and are far more put off by the costs.

Dip in mature students

There was a dip in the number of full-time mature students, defined as over 21, enrolling when tuition fees increased, but these numbers have now recovered to pre-2012 levels. However, part-time student numbers have fallen dramatically from 428,000 in 2010-11 to below 266,000 in 2015-16, representing a 38 per cent drop.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), says this group are more cautious about debt. “We have seen that school-leavers are not price sensitive, but part-time and mature students are,” he says. “If you have a job or you have children, you are less likely to want to take out loans and lose earnings. Plus the 30-year repayment period might look more daunting if you are already middle aged.”

In HEPI’s report, It’s the finance stupid! The decline in part-time learning and what to do about it, Mr Hillman writes that the drop in part-time learners is the “single biggest problem facing higher education”. The report suggests there is a need for more financial incentives for universities to be more flexible in their provision and for more financial support such as maintenance grants for this group.

This is a problem that needs addressing if university education is to remain accessible. In the 2016 Budget, a review of lifetime learning was promised and the Department for Education has confirmed it will go ahead under Theresa May’s government. But it has not started yet.

There is also another group of students to address – international students in the competitive global market for higher education. There are still high numbers of international students choosing the UK, but recently the previous healthy annual growth in numbers has stalled. For example, since the criteria for post-study work visas became stricter, there has been a consistent annual drop in the number of students from India.

After the Brexit vote, universities will be putting in a lot of work to reach out to EU students

Vivienne Stern, director of Universities UK International, is feeling positive though. She says: “Research we have done shows that satisfaction rates are high among international students who chose the UK compared with those who went elsewhere, for example to Australia or the US. We compare favourably on measures such as the quality of the research and teaching available as well as affordability and employment outcomes.”

Ms Stern says there is work to do to improve the experience for international students, for example in terms of helping them integrate better into the university and with their employment prospects once they graduate.

“We still need to work hard to attract international students and, particularly after the Brexit vote, universities will be putting in a lot of work to reach out to EU students,” she says.

Meanwhile, Universities UK continues to argue that international students should not be included in immigration reduction targets set by the government. This causes a conflict of interest between universities that want to attract foreign students and the Home Office which is trying to reduce the number of migrants.

HEPI’s Mr Hillman agrees that universities will want to reassure students, particularly from Europe, that the option is still open to come to learn in the UK, but he is confident that the reputation of British universities will hold.

“We are the only country in Europe that has universities in the top ten of the world rankings,” he says. “We’ll see what happens, but I don’t think we’ll necessarily see the huge drop in international students after Brexit that some are predicting. Now there is more incentive for the UK to reach out to students in Europe than before.”