Was the cobalt in your phone dug up by a child miner or the cotton for your clothes farmed by slave labour? How much CO2 was emitted or plastic wasted manufacturing the cars we drive? Impossible questions for the end consumer, and deeply challenging for producers themselves, but new technology could finally be providing sustainable supply chain solutions.

What problems are facing the modern supply chain?

As customers demand faster, more efficient services – without paying more – companies have had to become increasingly creative. The need to balance cost, speed and quality has led to supply chains getting longer, more complex, and much less transparent.

“We’ve spent decades shaping the supply chains we deserve,” says Simon Geale, senior vice president of Client Solutions at procurement consultancy, Proxima. “We’ve turned a blind eye to what’s happening beyond price and profit at that Tier One level.” Geale believes companies must start embracing the “4 Ps” – people, purpose, planet and profit – to unwind decades of values, habits and actions.

“A key challenge here has not altered for some time unfortunately” agrees Ursula Johnston Director at law firm Gowling WLG. “And that is the need for buyers to genuinely maintain transparency throughout their complex networks of suppliers. Properly assessing the way in which vendors operate, to ensure they comply with the standards which are promoted at the top of the chain will always be a challenge, but it continues to be what sets those who properly adhere to sustainability values from those that simply pay it lip service.”

How blockchain can aid supply chain sustainability

The first step is traceability. Something which, according to Doug Johnson-Poensgen, founder and CEO of Circulor, “hasn’t been truly possible until the advent of technologies like machine learning and blockchain.”

Circulor’s mission to improve traceability through a sustainable supply chain underpins their electric vehicle project with Volvo. This process is ripe for change as it relies heavily on cobalt, a product associated with child labour. Although only about 25 per cent of Congo cobalt might involve child labour, the raw material is mixed in with that of other countries at refineries, tainting everything. “The reality is that, when you get to the other end of the supply chain, the car manufacturer really has no idea whether stuff has been responsibly sourced or not.”

The project used digital twins and blockchain to track material from a mine, through refining and manufacturing, to the final product of an electric car battery. Once cobalt ore has been responsibly sourced, every step of its journey is immutably noted on a blockchain, so its exact provenance can be proved.

Once the ore reaches the refinery, a digital twin is created for it and fed into the manufacturing process. “We’re essentially saying that this amount of ore in, through this specific process, creates this amount of product out, testing for anomalies and whether mass, balance and time elapsed fit the recipe.” Every step is meticulously recorded, adding much-needed transparency.

Blockchain can also reduce waste, aid material recycling and, crucially, tackle carbon emissions. “In the not-so-distant future,” says Frank Clary, director of Corporate Social Responsibility at Agility Logistics, “costs will be applied to carbon in the supply chain. To ensure the quality of emissions reporting is trusted, blockchain will likely be used to make sure what’s emitted is what’s reported.”

Is blockchain really a sustainable solution?

Environment-saving technology can present something of a poisoned chalice, however. While artificial intelligence can make connections no human brain could, spotting countless efficiency gains, it takes as much carbon to train one AI model as five cars emit in their lifetime, according to recent research by the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Internet of Things sensors on factories can measure everything from air pollution to water quality to combat industry’s impact on the environment. The data these sensors gather, however, is processed in datacentres requiring huge amounts of energy.

Blockchain too has had its critics. PwC blockchain specialist Alex de Vries pointed out that the global power consumption for servers running the software for blockchain-powered Bitcoin is almost that of Ireland. But not all blockchain was created equal, explains Aparna Jue, product director at cryptocurrency platform IOHK, which claims to have created the “world’s most sustainable blockchain”.

“There are two methods of blockchain – proof of work and proof of stake. Proof of work, which Bitcoin is built on, involves brute force, puzzle-solving computational power. With this method you run a mining pool with many computers trying to solve a problem.”

Proof of stake, brainchild of IOHK (whose CEO Charles Hoskinson is also co-founder of cryptocurrency Ethereum), does not rely on such computational power. “Proof of stake is about how much stake you can put up to validate information, and you get paid network fees for being able to do that” says Jue, explaining that this makes proof of stake blockchain more sustainable through sheer reduction of energy usage.

How to get companies to buy into blockchain

Sustainable or not, the key to supply chain success is being able to prove blockchain actually works. “It can have the biggest impact in the larger supply chain,” says Jue. “That’s also where you find the most inertia among those in charge. So it’s better to test with small-to-medium use cases, de-risk it, and build success stories before selling the value proposition up.”

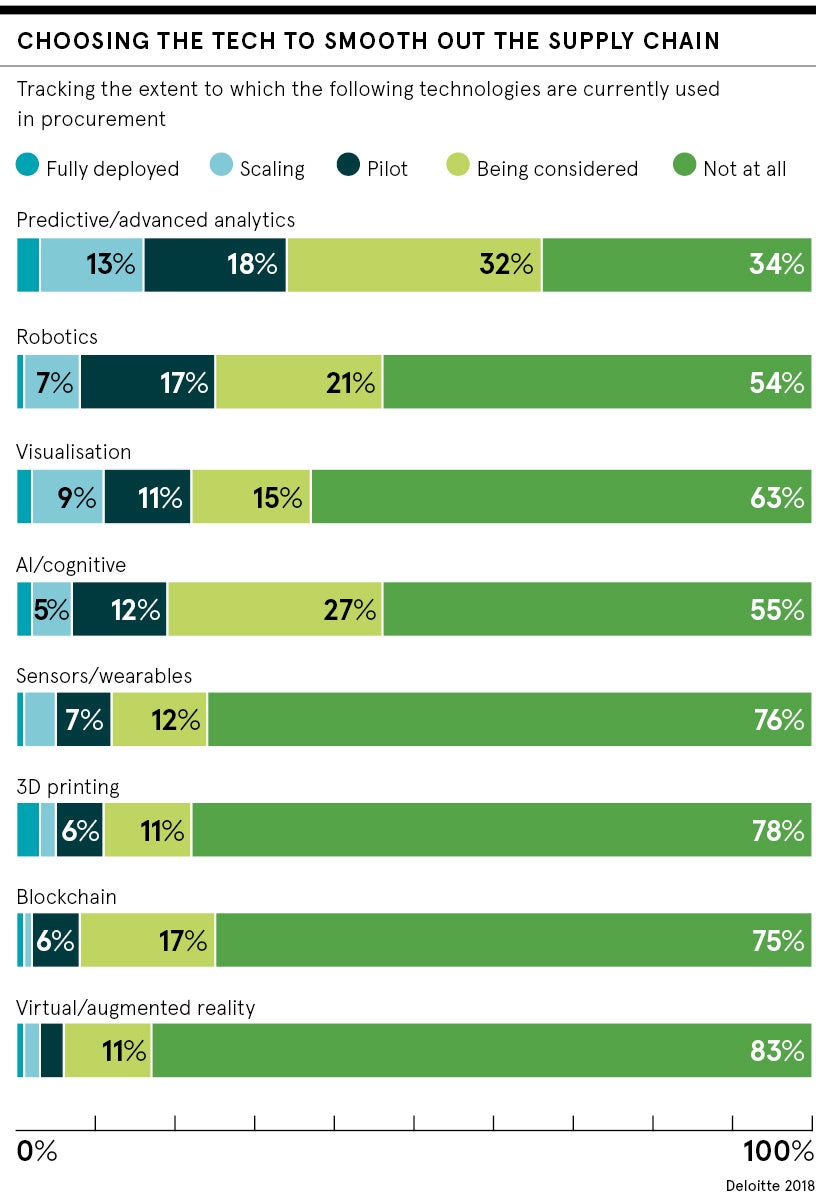

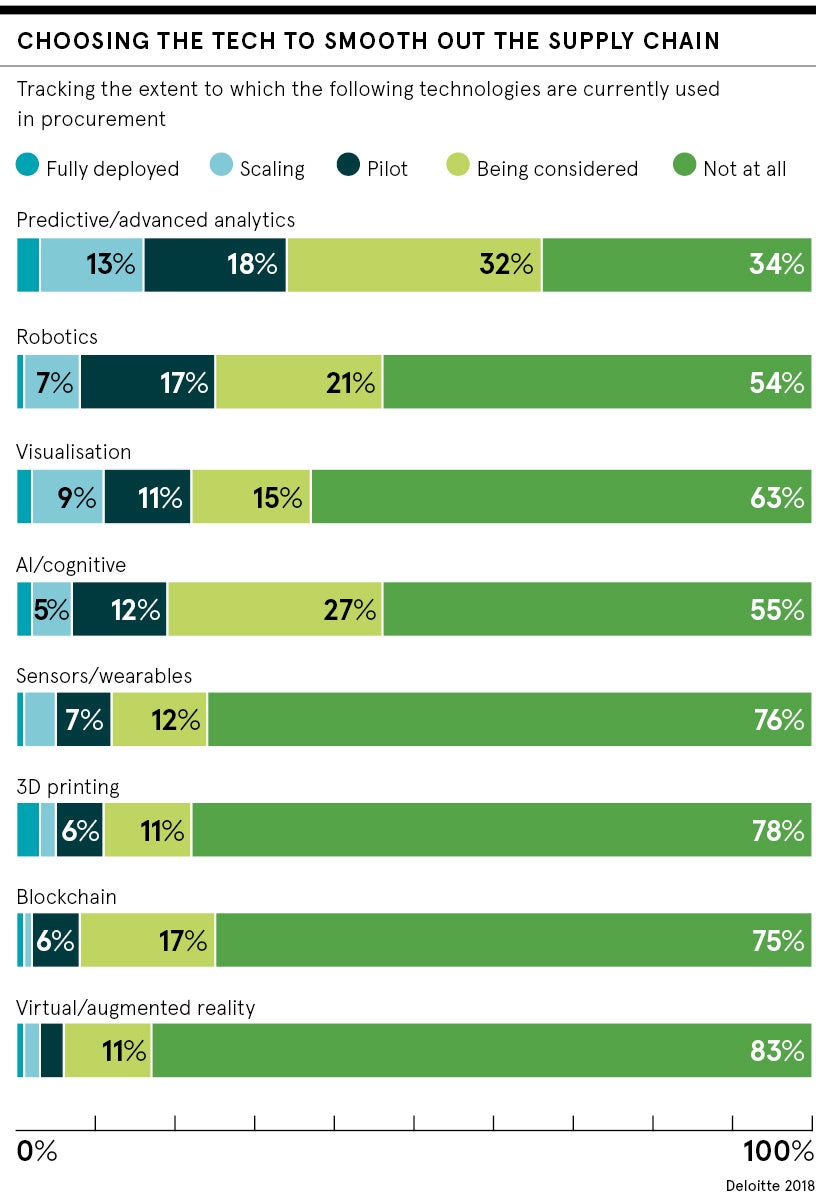

Johnson-Poensgen agrees. “It is very early days for the adoption of new technologies, such as blockchain and machine learning in supply chains, so it’s really only pioneers at the moment who are giving it a try.” Many large companies have spent vast sums of money on the technology itself without much reward, but tangible examples of success is beginning to generate some movement.

There are advantages beyond sustainability which make blockchain solutions more palatable. “It’s not controversial to say the digitisation of a process can make it more efficient,” says Johnson-Poensgen. “If you know where materials are flowing, you can reduce the working capital tied up in the supply chain, as well as administrative error and costly supply chain fraud.”

Armed with test cases and demonstrable efficiency gains, any supply chain manager looking to implement blockchain must consider one thing: change is often a mindset issue. “Reducing impact is not always expensive and a lot is behavioural,” explains Clary. “We might think reducing emissions means moving items on zero emissions vehicles or using asset technologies that we perceive to be new and expensive. But the reality is different. It is often an investment of time.”

Does sustainability really matter?

Ultimately it comes down to what kind of impact you want your business to have. Whether you embrace sustainability to make your supply chain more efficient, attract investment, or satisfy customers, it is a business objective which is now impossible to ignore.

“You can’t forget the ‘profit’ element of the people, planet, purpose, profit,” says Geale. “At the moment, not being sustainable could be a real growth inhibitor, and that’s a key risk appearing on the board’s agenda.” A tipping point has been painstakingly reached. “All the environmental tragedies we are witnessing, all these perfect storm moments are pointing us in one single direction.” Let us hope it is the right one.

What problems are facing the modern supply chain?

How blockchain can aid supply chain sustainability

Is blockchain really a sustainable solution?