Direct-to-consumer (D2C) companies have had it good. Podcast hosts rave about their benefits. Social media feeds fidget with their discount codes. Their subscriptions boxes slip through neighbours’ post-boxes. From pet food to house plants, lingerie to tuxedos, the direct-to-consumer boom has allowed for a whole host of spritely, millennial-friendly companies to make their mark in the last few years.

Trendy slogans and ethical postures are married with highly-detailed customer data and effective digital ads. D2C companies such as Warby Parker and Allbirds can control every aspect of their messaging, distribution and reputation.

“You can just have fun and create new things,” says D2C consultant Marco Marandiz, who calls it the “sexy” side to ecommerce marketing.

With high street stores shutting their doors, emergent digital-first brands are able to undercut mainstream providers by swiftly reaching out to discerning customers and delivering straight to their homes.

Customer service comes first for D2C

“D2C companies are what existed pre-club stores or mass-retailers,” says Nik Sharma, who invests in and advises many companies in the sector. “Every D2C brand is inherently a customer service company that sells a product.”

A more accountable and honest relationship between buyer and seller enables D2C companies to present themselves as being on the consumer’s side.

For an emerging brand such as Estrid, which delivers fuzz-friendly vegan razors, the direct-to-consumer model allows them to be upfront about their values. “We had been frustrated with the way women were portrayed in media and commercials, particularly by the major razor brands,” says founder Amanda Westerbom.

Every D2C brand is inherently a customer service company that sells a product

Vocal, very-online consumers are increasingly expecting D2C companies to reflect their own cultural prerogatives. Such centring of ethics – sustainability and body positivity in Estrid’s case – is critical. “The brands of today need to deliver societal and cultural value beyond a physical product,” says Westerbom.

Paying attention to the customer’s demands and desires is also smart business. “Most D2C brands will launch products based on what they hear from their customer service teams,” says Sharma.

But marketing directly to the people who will buy your product is hardly a counter-intuitive strategy; it is simply a leaner way of running retail operations. And yet, in a time when consumer spending has been disrupted and shopping patterns are turned on their head by the coronavirus crisis, some important questions have arisen about the long-term validity of the D2C model.

Unique challenges in an uncertain time

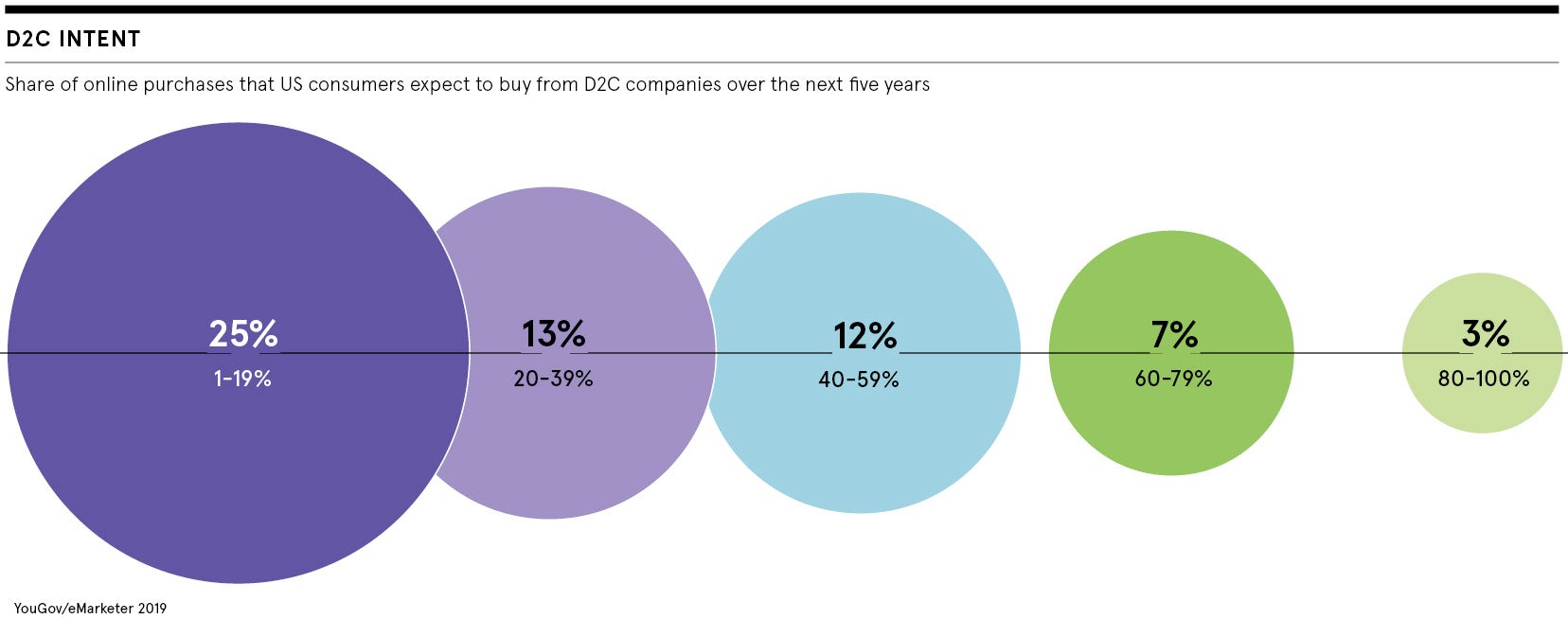

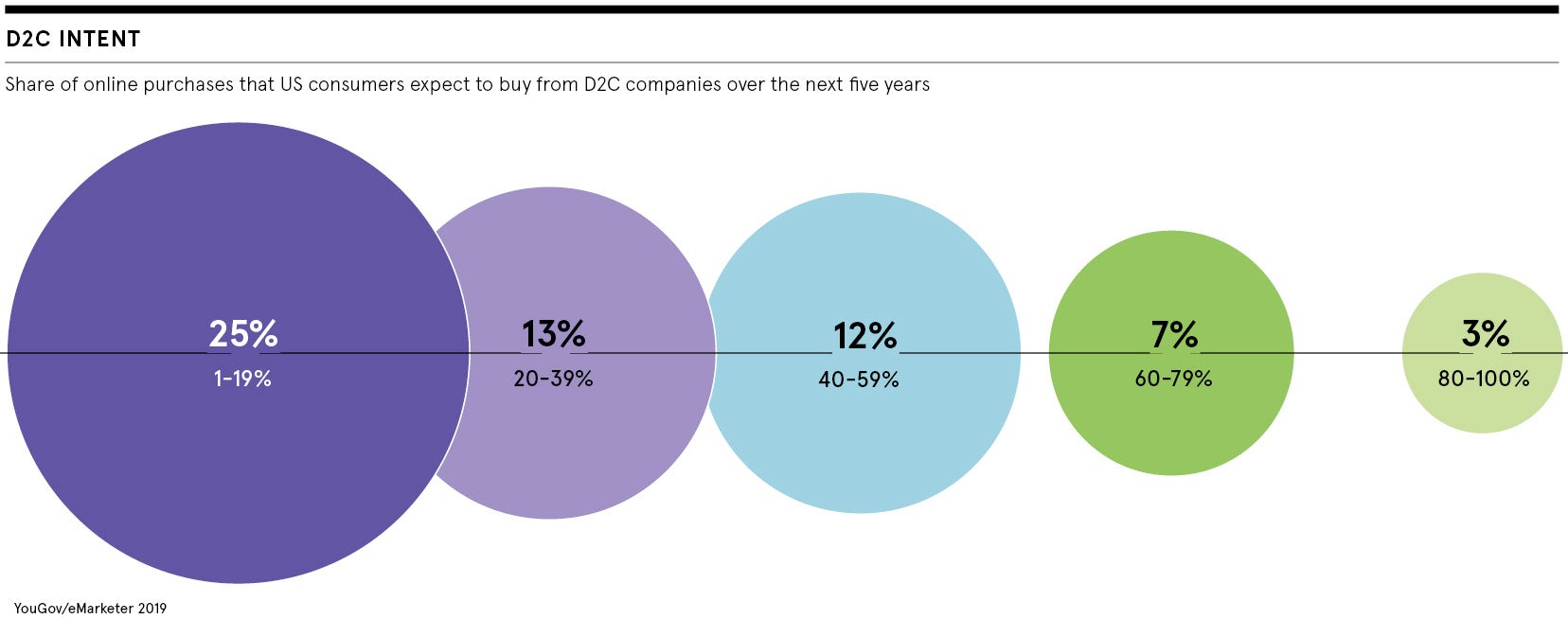

With public spaces reduced to no-go zones across much of the world, the consequences of the pandemic might have initially seemed like good news to many D2C brands already providing subscriptions services, home deliveries and digital-first customer service. Ecommerce exploded as more and more consumers became accustomed to ordering online.

Orla Weir, global D2C and brand manager for doorstep-delivered flavoured sparkling water startup Ugly Drinks, says: “We’ve seen uplift in grocery outlets and 400 per cent-plus growth online. In such a crazy and difficult time for the world, we have focused on where we can add value.”

While some more agile brands have been able to succeed, D2C companies in verticals like travel or leisure have suffered. Others, over-reliant on sleek marketing and messaging, took a hit for being, as Sharma puts it, “not functionally necessary”.

“Generally, the smaller you are and the more nimble you are, the better you can react,” says Marandiz. But even small brands are vulnerable to global supply chain disruption, like that provoked by the coronavirus.

With a global recession on the horizon, D2C challenges are unlikely to end here. Major retail players will no longer be focusing on traditional advertising and offline activation. Their budgets will go into channels until now enjoyed by D2C companies, Marandiz explains.

While a startup with a limited budget relies on its marketing spend to be efficient enough to acquire new customers, larger companies aren’t so bothered. And while it is a bonus, spending efficiently is far from necessary.

“By [larger companies] being inefficient, it makes it harder for smaller businesses to survive and to take their traffic and their customers away from them,” says Marandiz.

In turn, this could lead to a consolidation of the D2C space. Only the most successful brands will be able to survive a global recession while having to compete with the marketing spend of retail behemoths.

A shifting target audience

By primarily appealing to young digital natives who have money to splash on new products, many D2C brands appear as relatively upmarket.

When asked whether her company targets an affluent demographic, Estrid’s Westerbom stands firm: “We are on a mission to eliminate the pink tax and reduce the cost of razors for women; we believe the opposite to be true.”

Weir from Ugly Drinks argues a similar line. “We believe healthy products should be affordable and accessible for everyone,” she says. “We created Ugly as a down-to-earth alternative to fizzy drinks brands that charge a premium to enjoy ‘the good life’.”

Consultant Marandiz admits that while currently it is “primarily a middle-class and above industry”, times are changing. Once every customer demographic is used to buying products online, and data insights are available for every spending category, he says “we will start to see cheaper products at higher volume at the lower end of the market”.

Such an evolution is expected. For Sharma, D2C is “not a business model; it’s more just a channel of revenue”. Many brands already use the insights of the D2C channel to then scale their offering and move into larger, more traditional retail avenues. As the challenges ramp up, such flexibility will be key.

Customer service comes first for D2C

Every D2C brand is inherently a customer service company that sells a product

Unique challenges in an uncertain time