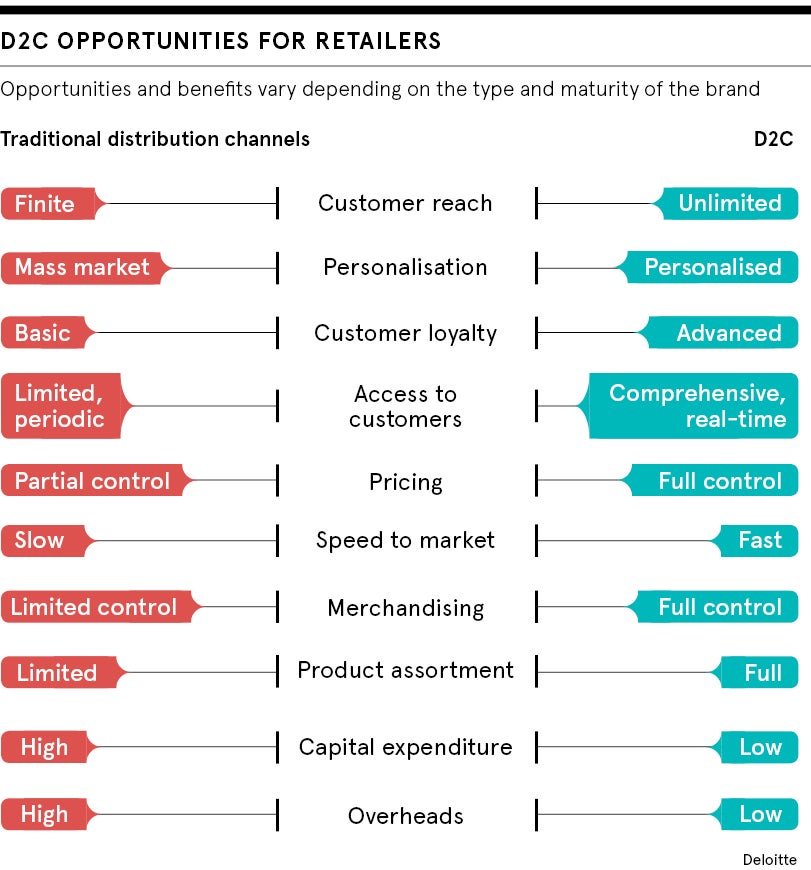

The chance to control your brand voice, no jostling with competitors for shelf space and real-time feedback from customers on what they like and what they’re indifferent to. The benefits of the direct-to-consumer (D2C) model are varied and very tempting.

It seems like every other day we hear of another old high street bulwark shuttering stores or see a virtual retailer with a super-streamlined website announcing eye-watering profits, so it’s no surprise that D2C is considered the modern option by many.

The markups are huge and the retailer often takes up to 60 per cent of the price, so you have to inflate your price to break even

Industry newcomers and veterans alike are increasingly choosing to shake off the shackles of the middleman and go it alone, with new innovations such as subscription boxes and buyer’s clubs giving the consumer more choice. But how far can the movement go? And what limits exist?

How D2C can champion brand transparency and uniqueness

Much of the appeal of D2C has to do with a desire for knowledge on the part of consumers and a desire to stand out on the part of brands. The entrepreneur behind Fit Flop, Bliss and Soap & Glory, Marcia Kilgore launched Beauty Pie in 2016. Its luxury beauty products can be purchased from their website for a luxury price tag or instead customers can pay £10 a month membership and buy the products at cost price. An otherwise £100 night cream is just £11.33 for members, while a £20 mascara comes in at £3.36.

According to Ms Kilgore: “Consumers want so much information these days, there’s nowhere for brands to hide, and you shouldn’t have to. If you execute your ideas well and don’t cut corners, retail isn’t hard.”

Transparency is Beauty Pie’s bread and butter, and their website lists the full breakdown of every price, including packaging, development and raw ingredients. There’s no way Beauty Pie could offer their super-low members’ prices if they had to factor in the costs of a department store outlet.

“High tech skincare does have some expensive ingredients, but by the time you get to retail, the cost could be ten times that, easily,” she says. “The markups are huge and the retailer often takes up to 60 per cent of the price, so you have to inflate your price to break even. You end up compromising on the quality of the product somewhere and that’s not good for consumers or for the brand.”

Things to be aware of before launching a D2C model

One thing that helped ease consumer anxiety about buying direct from a brand has been low-cost shipping and painless returns, something subscriptions specialist Steve Price warns isn’t sustainable. “There’s a ceiling to how long brands will be able to continue offering free shipping without ending up in financial or logistical trouble,” he says.

Another factor that may give brands pause for thought is that many large retailers invest heavily in their own brands. “If you search for batteries on Amazon, the first thing that will come up is their own Amazon Basics line,” says Mr Price.

Ms Kilgore adds: “If you’re stocked someplace else, that retailer will get all of your sales data in real time. They’ll know exactly what’s selling and why, while you’re scrambling to stay on top of things. Sometimes, they will even copy whatever’s working from your brand; why wouldn’t they, when they have all that sales data?”

The simple genius of subscription boxes

Another way that D2C brands are making a splash is through subscription boxes and plans. “The subscription box industry is projected to be worth $1 billion by 2021,” says Mr Price. “I keep a personal list of all the new boxes I see launching and about 50 per cent of my list launched just last year.”

The boxes largely fall into two categories: “surprise and delight” is a tailored treat delivered every month, such as Craft Gin Club, The Cheese Geek or Birchbox, which sends a selection of curated beauty products. Then there’s everyday essentials, such as pet food, coffee beans and, most notably, razors.

“Gillette had something like a 74 per cent share of the shaving market in 2012. Just four years later, that was down to 50 per cent,” says Mr Price. What resulted in such a drop? The arrival of brands such as Harry’s, a D2C offering founded by Andy Katz-Mayfield and Jeff Raider, which enables customers to sign up for a shaving plan. You’ll get premium German-made blades and other shaving paraphernalia delivered to your door, with a Harry’s blade costing £1.88 to a competitor’s £3.05.

UK general manager Matt Hiscock explains their personal touch. “Because of our close relationships, we receive tons of feedback from customers that helps us make improvements to our products,” he says. “For example, we added a trimmer blade to our second generation razors because we received so many requests from customers saying how much more beneficial it would be to their shave.”

The conglomerates have been taking notice, with Unilever acquiring similar brand Dollar Shave Club for $1 billion in 2016, Colgate-Palmolive taking a minority stake in contact lens subscription service Hubble and Nestlé taking a majority stake in Tails.com, the tailored dog food delivery service.

What do D2C brands need to do to stay on top?

In many ways, it’s an extension of culture we already choose with many of us having Spotify, Netflix or Amazon Prime subscriptions. D2C enables brands to immerse customers in their ecosystem and control their messaging from the point of purchase right through to customer service. The experience feels more personalised for the customer, as well as being cheaper per product and more streamlined. The model is yet another threat to the traditional retail landscape. As Mr Price puts it: “There are a lot of ghosts on the high street.”

Of course, that’s not to say that going D2C is a magic bullet. As Mr Price notes, consumers aren’t loyal in the same way to FMCG. “No one feels an affinity to the company that delivers them fish food. It’s a service,” he explained. “These brands need to offer something extra, like a magazine or some kind of treat to make the experience feel special and exciting, and really make the most of what’s in that box.”

Dollar Shave Club, for example, sends out the non-shave-related _MEL Magazine_, while D2C beauty brand Glossier include stickers and free samples. Free shipping isn’t enough – nor will it last forever – so to keep people buying, customer service is incredibly important. And there’s no shortcut for that.

How D2C can champion brand transparency and uniqueness

Things to be aware of before launching a D2C model

The simple genius of subscription boxes