In April 2013, 1,134 people died in the Rana Plaza garment factory collapse in Dhaka. The ensuing Bangladesh Accord on safety notwithstanding, action on ethical issues endemic in fashion supply chains has since proved sluggish. Four years on and numerous sweatshop exposés later, fast fashion is making only slow progress.

Why?

Why?

Admittedly, the sector is a plus-size model. Businesses are global, supply chains complex. Expectations of transformation therefore need to be realistic, says Sass Brown, founding dean of DIDI (Dubai Institute of Design and Innovation). “Change is a process. We are trying to change the direction of an industry that is the third largest in the world. That requires a major culture shift and that takes time,” she says.

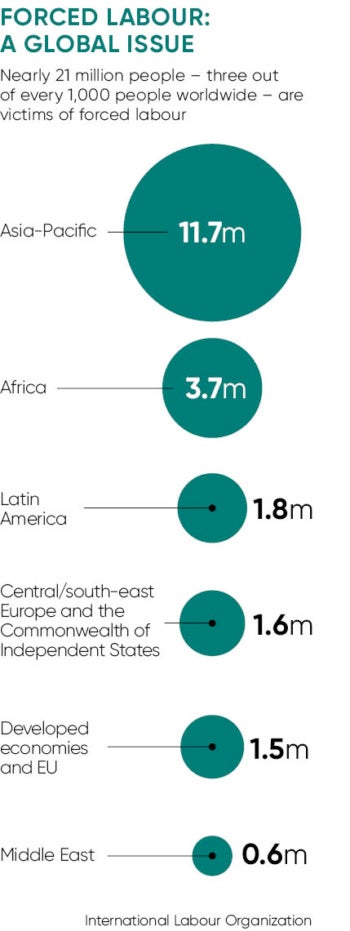

True though that may be, time is not on the side of those suffering exploitation. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates there are 21 million victims of forced labour worldwide and 168 million in child labour, down from 246 million in 2000. In joint research by the Ashridge Centre for Business and Sustainability, and Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI), 71 per cent of companies admitted the likelihood of modern slavery in their supply chains.

Putting policy into practice

Tackling matters head on, the UK government has taken a global lead on legislation, with the Modern Slavery Act 2015 imposing reporting requirements on organisations with at least £36-million turnover. Policy is one thing, though, practice another.

According to Carry Somers, founder and global operations director at Fashion Revolution, most brands do ban child labour within their supplier code of conduct, but many fail to police performance, leaving themselves and their consumers in the dark. “The majority of fashion brands have little or no supply chain transparency down to raw material level,” she says. “Child labour is still rife in cotton fields, as well as in ginning and spinning, so how do consumers know they aren’t supporting it with the next garment they buy?”

Fashion Revolution believes the first step towards transparency and transformation starts with one simple question, “Who made my clothes?” On April 24, every year, people are encouraged to wear garments inside out for Fashion Revolution Day, displaying brand and maker labels, to mark the Rana Plaza anniversary.

Maintaining you cannot tackle exploitation unless you can see it, Ms Somers considers transparency a prerequisite for improving conditions and collaborative action. Public scrutiny and consumer demand will then drive change. She contends: “We are seeing greater levels of disclosure mainly because citizens are holding brands to account – transparency is becoming obligatory. It is coming at companies, like it or not.”

Collaboration is particularly important in tackling exploitation and child labour, says Safia Minney, founder of fair trade fashion pioneer People Tree, managing director of Po-Zu and author of a forthcoming book Slave to Fashion. “While there is progress in mills and factories to reduce child labour, there is a long way to go,” she says. “Each country has different laws about the age and hours a child under 18 can work, but these are largely ignored. NGOs and trade unions are essential to social dialogue.”

Ms Minney proposes an advocacy role for companies, suggesting they use their influence.

“Mainstream fashion brands have a responsibility to put pressure on governments of developing nations to promote workers’ rights,” she says.

We are seeing greater levels of disclosure mainly because citizens are holding brands to account – transparency is becoming obligatory

According to Lotte Schuurman, of the Fair Wear Foundation, it is this ability to leverage buying power that could prove transformative. She says: “The purchasing practices of Western garment brands have a huge influence, positive or negative, on the lives of garment workers in clothing factories. Garment companies can use their economic influence to make an actual change.”

In principle, procurement decisions could have not only reputational consequences but real beneficial impact on people and communities. In practice, though, results are mixed, says David Noble, group chief executive at the Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS). “Retailers confidently state their supply chains are free from malpractice. However, the sad fact is many still lack the basic procurement skills to even detect it, let alone prevent it,” he says.

Performance might be patchy, but not for want of tools and training. The Ethical Trading Initiative was created as long ago as 1998 and its ETI base code, founded on ILO conventions, has become internationally recognised. The Sustainable Apparel Coalition launched the Higg Index in 2012, providing a suite of assessment tools, plus CIPS produced a guide to Ethical and Sustainable Procurement in 2013, with input from the Walk Free Foundation. In addition, 2017 should see publication of the long-awaited international standard for sustainable procurement, ISO 20400.

So, if the ethical call to action is getting louder and help available, why does progress remain slow?

Failure to turn good intentions into better practice is partly down simply to reluctance to allocate resources, argues chief executive of Segura Systems, Peter Needle. “Many retailers talk about ethical issues in supply chains and the need to address them, but when it comes to spending money to rectify problems, they are more reluctant,” he says.

“The major problem for most is they have no control or visibility over what suppliers do on a day-to-day basis, so the system is still largely built on trust. The question is, ‘If a factory is seen to be ethical on Monday, will it still be so on Friday?’”

One-off or periodic audit and mapping tools have been available for years. Moving from such point-in-time information on suppliers and factories to real-time actionable data is seen by Mr Needle as the investment game-changer. New technology solutions not only help monitor production live but also ensure approved sourcing.

As a provider of cloud-based supply chain technology, Segura already works with leading high street names. However, fashion is typically anything but fast when it comes to tech, which could ultimately prove critical, maybe even fatal. Mr Needle concludes. “Brands and retailers have been slow to adopt new technologies. If they remain so, there is a perfect storm brewing of consumer demand, NGO pressure, journalistic reporting and new agile, ethical competitors, that could see many of them go out of business, possibly much sooner than they think.”