The year was 2007. Tony Blair was still prime minister and Sheffield United were in the Premier League. The iPhone had yet to reach the UK. It was a different time – time for Plan A.

Originally billed as an “eco-plan”, the first Marks & Spencer five-year Plan A launched that January. Its 100 commitments included becoming carbon neutral and sending zero waste to landfill.

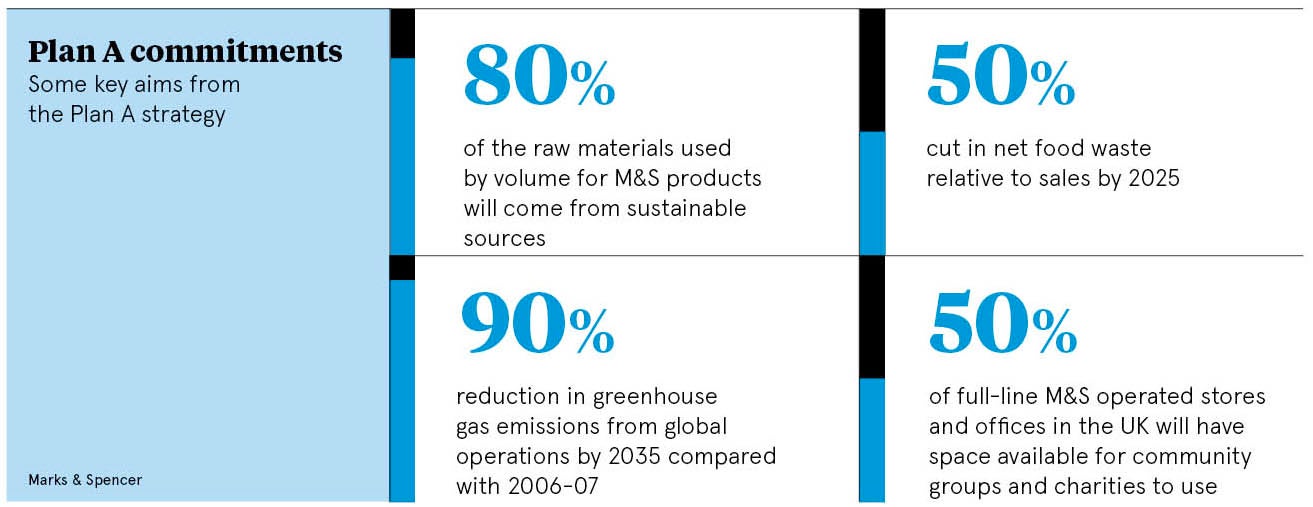

Fast forward to 2017 and Plan A 2025 marked the tenth anniversary with 100 more commitments, including bold overarching ambitions to help ten million people live happy, healthier lives, transform 1,000 communities and be a zero-waste business.

Plan A is a mammoth undertaking. So far, M&S has delivered no fewer than 296 commitments, failing only 21. For Mike Barry, director of sustainable business (Plan A) at M&S, a unifying strategic value is what keeps it core to the business. “Plan A makes us more than a sum of the parts,” he says. “Rather than just 100 individual pieces of work going on, we have something that makes sure the business is consistent in what it does.”

The scope of Plan A ambition makes sense in the context of the sheer scale of the M&S retail operation. Any business selling 35,000 different product lines to 32 million customers must manage a diverse and complex global supply chain. From salmon-farming in Scotland to cocoa-growing in West Africa, supply routes encompass some 20,000 farms, plus thousands of factories and raw material sources.

At product level, the requirement to have a Plan A “quality” standard – an eco or ethical benefit above the market norm, such as being Fairtrade or RSPCA Assured – drives supply chain sustainability, with 79 per cent compliance already.

At producer level, M&S has also led the way in putting a factory map up on its website, sharing what happens where in the world, not just for clothing and home products, but food too.

Supply chain visibility and transparency remain a major challenge for retail though. Along with adidas and Reebok, M&S came in the top three of Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2017. However, the sector has a long way to go on disclosure, explains Carry Somers, founder of Fashion Revolution. “Fashion supply chains are still fragmented and greater transparency will be key to transforming the industry,” she says. “If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it.”

Seeking supply chain transparency, tier by tier, is a tough ask of any one business alone, says Will Schreiber, a partner at 3Keel. “Most significant environmental and ethical sourcing risks happen far upstream in supply bases,” he says. “Collaboration is critical to addressing these across the industry and we’re starting to see convergence of standards.”

Whether tackling deforestation impacts of Brazilian soy production or sourcing better cotton in India, action-orientated collaboration can help, agrees Louise Nicholls, corporate head of human rights, food sustainability (Plan A) and food packaging at M&S. She says: “There are some great examples where the supply chain has come together with government and NGOs, and really driven change. The UK Modern Slavery Act, for instance, recognised the need to establish a level playing field because, in that case, regulation was actually good for business.”

Collective response is the only effective way forward on modern slavery, says David Camp, programme lead at business-led multi-stakeholder initiative Stronger Together. “Slavery was abolished over 200 years ago, but never eradicated and there are more people in slavery today than ever before,” he says. “Retailers and brands play a crucial role, and it is essential competitors come together to develop consistent approaches, increase commercial leverage and speak with one voice. Collaboration is absolutely essential for changing the norms that have come to exist over decades and generations.”

The reality is a criminal element in the supply chain is taking advantage and exploiting workers

A founder member of Stronger Together, M&S has published two human rights reports and last year topped the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark for fashion and food. M&S sponsors the UK modern slavery hotline, and its open-source modern slavery toolkit is also available to all suppliers and outside firms.

Despite all of this, plus the fact that 19 Plan A 2025 commitments are specifically about human rights, the threat of forced labour persists, Ms Nicholls acknowledges. “I don’t think it’s a case of if we find modern slavery, it’s when we find modern slavery. The reality is a criminal element in the supply chain is taking advantage and exploiting workers.”

Openness and pragmatism are paramount, she adds: “It’s not that you’ve got the issues that matters, it’s what you do about it. We are much more concerned about getting victims to safety, remediating issues, and if possible bringing criminals and perpetrators to justice. That’s what matters to us.”

Looking ahead to the next ten years of Plan A, 2025 and beyond, M&S is building supply chain resilience by working lean. It is also anticipating game-changing supply chain impacts of a fourth industrial revolution, from blockchain and beef DNA, through robots and drones, to 3D printing and artificial intelligence.

In all of this, though, expect one constant, concludes Mr Barry: “One thing about sustainability is that it is a long-term systemic programme. Faced with disruption in the marketplace, environmentally, socially and economically, M&S will never stop driving sustainability into everything it does.”