In an era of unprecedented supply chain complexity, it’s clear to see why the role chief procurement officers (CPOs) play in global enterprises has become increasingly crucial.

In fact, a survey by recruitment agency Korn Ferry found that 82 per cent of CPOs now have direct access to their chief executive, up from 60 per cent in 1999.

Forward-thinking and adaptable CPOs are able to deliver cost-savings across their business, at the same time as mitigating potentially damaging supply chain risks. The renewed pressure on supply chain integrity has brought CPOs to the forefront of organisation-wide decision-making.

However, political uncertainty on both sides of the Atlantic is turning previously uncontroversial procurement decisions into high-profile news headlines and drawing uneasy CPOs into politicised debates.

New passport contract comes under fire

After the Home Office awarded the contract to produce post-Brexit blue UK passports to Franco-Dutch firm Gemalto, over the UK’s De La Rue, many Brexit supporters criticised the choice, even though government ministers insisted the tender was fair and rigorous.

“The Home Office tender will have set out its requirements for the new passport, including ‘good value’ terms and other issues such as security, with the contract awarded to the organisation that best met those conditions,” says Nick Barnett, MSc purchasing and supply chain management course leader at Westminster Business School, University of Westminster.

“The problem for some in the media was it was not awarded to a British company. Of course, it is an emotive issue in this case, but it shows how easy it is in the current climate to be drawn into a debate that is not about overall business value.”

The Home Office awarded the new British passport contract to Franco-Dutch firm Gemalto, over UK firm De La Rue

Procurement does not happen in a vacuum

In a perfect environment, the only factors CPOs would consider when making any procurement decision would be around value and cost. Yet the procurement function is not insulated from other business areas and CPOs will undoubtedly be influenced by the current political climate, alongside the opinions of C-suite colleagues. CPOs have always faced external pressures and a central part of the role is to weight these different perspectives objectively.

“There are obviously risks associated with offshoring work, but a good CPO and their procurement team would ensure that their procurement process fully evaluates these risks and develops appropriate mitigations,” says James Bousher, operations performance manager at international consultancy Ayming UK.

For CPOs managing international supply chains, taking the emotion and politics out of procurement can only be achieved when their decision-making process is as robust and transparent as possible

For CPOs managing international supply chains, taking the emotion and politics out of procurement can only be achieved when their decision-making process is as robust and transparent as possible. If the reasoning behind a procurement choice is sound, then CPOs will be well positioned to react and adapt to any policy changes, rather than being controlled by unexpected political disruption.

“For example, the burgeoning trade war that the US is instigating may create some headaches for CPOs if prices start changing, but it’s not going to launch a raft of politically motivated procurement decisions. Ultimately, the foundation of good procurement practice is about isolating the process from unrelated outside influence and delivering the most optimal outcome for their company,” says Mr Bousher.

What will Brexit mean for the future supply chain?

It’s still not clear what form Brexit will take, with a soft Brexit that sees the UK maintain favourable trade terms with the European Union or a hard Brexit that disrupts supply chains both being in the realm of possibility. Preparing contingency plans for a hard-Brexit scenario is a prudent course of action.

“Segmenting your supply chain is a key step for decision-makers, ensuring you know which items can be quickly switched to other suppliers or countries if there’s an issue or, if substitution is more difficult, developing contingency plans should something negative arise,” adds Mr Bousher.

But pre-emptively breaking supply chains based on fear of the unknown can be problematic. According to a Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply survey, 45 per cent of businesses in the EU are in the process of finding local companies to replace UK suppliers, with 32 per cent of British businesses seeking local firms to take over from EU suppliers.

If a Brexit with few tariffs is realised, then the companies that, for example, withdrew their manufacturing operations from the UK will have done so unnecessarily and at a cost to the business.

CPOs must ensure they have a watertight back-up plan

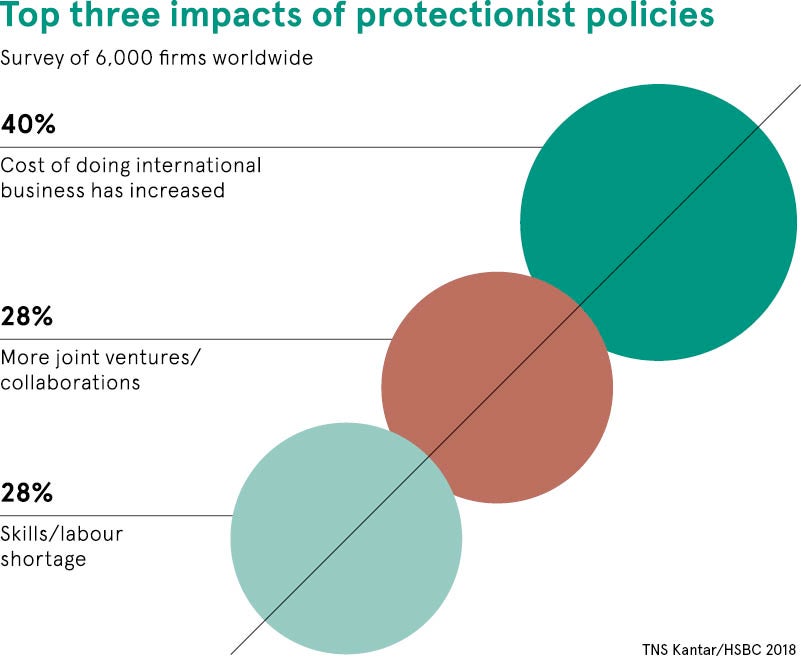

From US President Donald Trump imposing tariffs on imports, an unclear Brexit deal and the rise of protectionist rhetoric in a number of European countries, the challenges facing CPOs are numerous and it’s virtually impossible to avoid all the knock-on effects this volatility will have on global supply chains.

By proactively assessing the most at-risk elements of the supply chain and creating comprehensive back-up plans should these links be broken, CPOs will ensure a fact-based conclusion is reached.

“A CPO’s role is to deliver the best results in procurement for the company that they work for. If, following the evaluation of a well-run procurement process, a CPO is offered the option of significant savings from an equivalently well-qualified international supplier, or a local supplier, most wouldn’t bat an eyelid in banking the savings,” Mr Bousher concludes.

New passport contract comes under fire