Procurement officers often sigh over the misapprehension that their job is all about cost-cutting. For government procurement officers, the penny-pinching reputation is even harder to shake.

“The perception is that we only buy on cost,” says Gareth Rhys Williams, government chief commercial officer. “But I can’t ever remember a contract where cost was the only issue.”

Mr Rhys Williams, who has been in post for just over two years, is on a mission to change a number of similar perceptions. He has led a serious drive to upskill central government’s commercial arm, a drive that began with his appointment from the private sector, where he was chief executive of workplace services supplier PHS Group and Charter plc before that.

Quality in procurement is just as important a factor as cost

In a blog post a mere 14 weeks into the job, he said it was clear “that there are real opportunities to make huge savings for taxpayers and improvements in service levels, through better-designed contract negotiation and ongoing management”.

“Government had recognised that we had underinvested in our commercial skills set,” he says. “If we are fluffy about contract design and how we score the quality elements in a tender, price will become the determining factor. We need to be much more sophisticated about how we drive quality and get much better about making those quality elements more precise. It’s up to us to make the quality assessment very granular.”

We need to be much more sophisticated about how we drive quality and get much better about making those quality elements more precise.

Innovative assessments of suppliers can help provide that element of quality. A recent selection process for a £1.3-billion investment programme at submarine bases on the Clyde involved a series of interviews and workshops to assess how collaboratively the bidders were able to work.

The procurement process was discussed with potential bidders beforehand; behavioural experts observed, scored and helped to evaluate the behaviours of each firm in a series of practical exercises running over several days.

Companies were required to develop objectives with the Defence Infrastructure Organisation, discussing how they would approach and implement the work. It was, according to the contractors taking part, “a refreshing way to do business [and] a huge leap forward from a procurement perspective”.

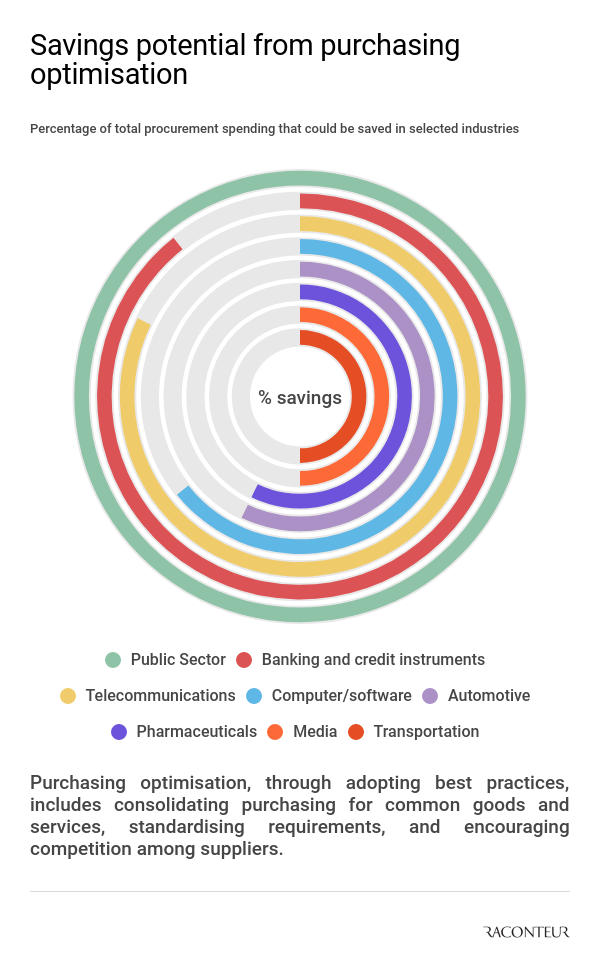

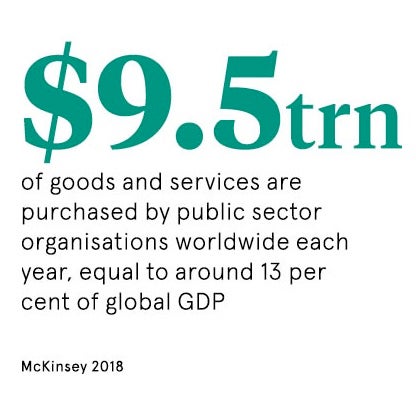

Smarter procurement can save money

Not that cost is overlooked; a recent McKinsey report found public sectors around the world could save about 15 per cent of their spending through smarter procurement, which given that the UK government’s commercial function spends about £49 billion every year on external contracts, is not to be sniffed at.

Part of ensuring that quality is at the forefront of everyone’s mind involves getting the procurement specialist in early and the department has been developing cross-functional teams, ensuring commercial experts are involved in contract design from the get-go.

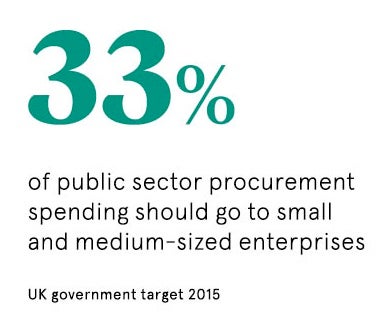

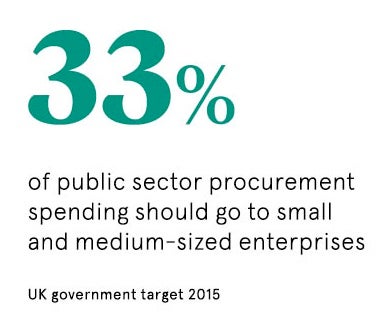

Making sure government contracts are available to as wide a range of suppliers as possible is another part. In August 2015, the government set a target of 33 per cent of spending to go to small and medium-sized enterprises, a target Mr Rhys Williams describes as “a tough goal, but a good one”.

“We have to make ourselves easier to deal with and have changed a lot of our processes, such as only asking for supplier information once,” he says. “It’s not in our interests to buy only from big vendors; we want this to be as innovative a process as possible. But there are a lot of unintended consequences in this game; if you award a contract to a small-sized supplier one year, it might turn them into a big supplier. Does that mean we can’t award them a contract next year?”

Encouraging good behaviour throughout the supply chain

Much of the work in changing behaviour involves changing the way big suppliers do things and bringing in measures that encourage good behaviour all the way down the chain. So, for example, it is currently mandatory for all government suppliers to pay their sub-contractors promptly and the commercial function is consulting on ways of eliminating those companies that fail to pay within 30 days, even on non-government work.

“The devil is in the detail,” says Mr Rhys Williams. “We are making sub-contracting opportunities more available. We recently made it mandatory for our suppliers winning contracts worth £5 million or more to advertise any sub-contracts above £25,000 via Contracts Finder [the government website that publicly advertises current contract opportunities].”

Since the start of 2017, more than 22,000 suppliers, almost two thirds of whom are small businesses, have signed up to Contracts Finder, according to figures from the Crown Commercial Services. But increasing procurement from smaller businesses can mean increasing the workload for the procurement department.

The challenges of higher-quality procurement

“There’s a trade off,” says Mr Rhys Williams. “We have disaggregated a lot of the larger IT contracts. But if you chop a contract up into 300 smaller contracts, you need more civil servants to manage that.

“It’s all about driving a higher quality of procurement and we need to be crystal clear about evaluation in order to do that.”

It’s all about driving a higher quality of procurement and we need to be crystal clear about evaluation in order to do that

So, for example, it may be politic to award contracts in such a way as to help regenerate unemployment blackspots, with suppliers promising to take on a certain proportion of long-term unemployed. But if those long-term unemployed don’t have the skills set required for the contract and need huge amounts of retraining, it may not produce the best-value outcome.

“It’s all about relevance and proportion, and thinking through the wider agenda,” says Mr Rhys Williams. And that brings us back to the quality of the staff at his command. It’s not just about cost, it’s about quality.

Quality in procurement is just as important a factor as cost

Smarter procurement can save money