Dawn Bilbrough, a critical care nurse from York, posted on Facebook: “I’ve just come out of the supermarket. There’s no fruit and veg, and I had a little cry in there. I’ve just finished 48 hours of work and wanted to get some stuff in. People who are stripping the shelves, stop it, please.”

As COVID-19 took hold in the UK last month, essentials such as pasta, toilet paper and vegetables rapidly sold out in stores across the country. Many frustrated shoppers took to social media to share photos of empty supermarket shelves and to accuse others of acting selfishly by panic buying.

But so-called food hoarding is just part of the problem. How have supermarket supply chains responded to dramatic changes in shopping habits? And could the current crisis alter global supply for good?

The effect of ‘panic buying’ on UK supermarkets

The sight of empty shelves will have frightened many. But Tom Holder, from the British Retail Consortium (BRC), insists there hasn’t been a shock to supermarket supply chains so far. “It’s a demand issue,” he says. “The real challenge has been to get things to the stores and then onto shelves fast enough before people buy them again.”

If for domestic political reasons a country restricts exports then others might follow… That would play out in reduced availability and higher food prices

This was amplified by the sudden closure of schools, restaurants and cafés. To cope, supermarkets have hired more staff and increased in-store production of products such as bread, says Holder.

Products, such as pasta, toilet paper and orange juice, have been more popular during the pandemic. Tesco, which saw sales increase by around 30 per cent in March, says it has adapted by working closely with supplier partners to simplify its range and allow more popular products to get onto shelves during the lockdown.

Now as panic buying eases, UK supermarkets face fresh challenges. Holden says restrictions on numbers allowed into stores has already brought profits down for some and it remains to be seen how people will react when restaurants reopen.

Global supply chains at risk

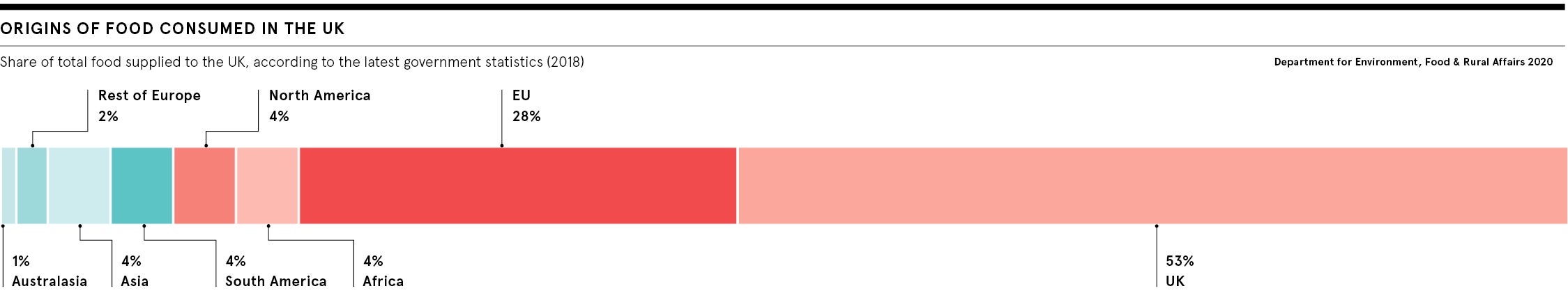

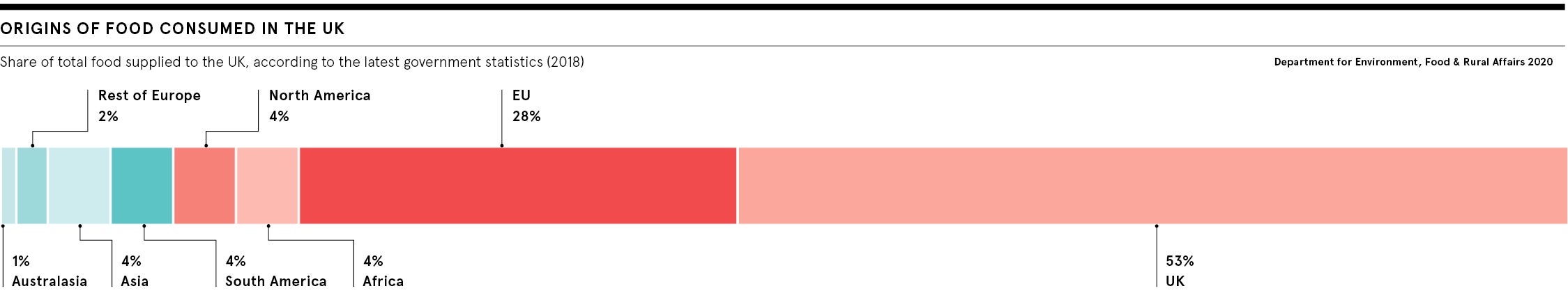

But bulk buying isn’t the only strain on supermarket supply chains. According to government figures, half of the food consumed in the UK comes from overseas and some degree of disruption to global exports is inevitable during a pandemic affecting every continent.

Christopher Smelling, head of policy at the Freight Transport Association (FTA), says there have already been “some delays and irregularities in goods coming from the most affected areas, such as northern Italy”. However, he adds that, despite the strict lockdown in Italy, “the goods have always been moving”.

Dr Peter Alexander, a global food security expert at Edinburgh University, says he is concerned about what could happen to international trade as the crisis continues. “If for domestic political reasons a country restricts exports then others might follow. You would then get this cascading snowballing effect,” he says. “That would play out in reduced availability and higher food prices.”

This can already be seen in some countries. For example, Vietnam, the world’s third biggest rice exporter, temporarily suspended rice export contracts. Russia, the world’s biggest wheat exporter, could threaten to restrict exports. And Kazakhstan reportedly banned exports of wheat flour.

A shortage of field workers around the world, due to illness, restrictions on movement or economic crisis, could also threaten global food trade and supermarket supply chains.

Maximo Torero, chief economist at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, warns countries not to adopt protectionist measures. “Now is not the time for restrictions or putting in place trade barriers,” he says. “Now is the time to protect the flow of food around the world.”

The business world could look to local suppliers

With risks to global supply chains, Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City, University of London, points out that UK supermarkets could make better use of localised suppliers. “We have rich, amazingly productive land that we’re underusing,” he says. “We already have a fragile food system and now there are hiccups emerging from Spain and Italy.”

The UK should increase horticulture planting to make the system more robust, Lang adds, calling on the government to issue guidance on healthy and sustainable food purchasing while global supply faces disruption.

However, shifting to use of more local suppliers isn’t straightforward, according to BRC’s Holder. “The types of things supermarkets can get locally they generally do,” he says. Most already source local meat like chicken, for example.

Staffing must also be considered. The pandemic and its restrictions on travel could mean UK farms won’t be able to rely on temporary staff, many of whom come from eastern Europe each year to harvest crops. As a result, the government has called upon millions of students and furloughed workers to “pick for Britain”, as well as issuing permits to pickers from Romania.

Long term changes to supermarket supply chains

Lifting lockdown in the UK and around the world is likely to lead to further changes in shopping habits. One possibility is that people flock to restaurants again in large numbers.

FTA’s Smelling says it could take a few days for catering venues to restock. “If the government announces on a Tuesday you can open the restaurants and the pubs, it doesn’t mean they’ll all be able to open on Wednesday,” he points out.

Further down the line, there could also be increased demand for “healthy” foods, as well as renewed calls for food to be sourced closer to home. Alexander at Edinburgh University expects things won’t return to the way they were. “However, the exact state they return to is still unclear,” he says. “But I’m more optimistic than I am pessimistic.”

The effect of ‘panic buying’ on UK supermarkets

If for domestic political reasons a country restricts exports then others might follow... That would play out in reduced availability and higher food prices

Global supply chains at risk