Personalised medicine promises to transform health care, by using targeted drugs that are more effective in treating disease. There is great potential to save more lives or at the very least help patients to manage their condition, and live longer and better.

This new generation of treatments, based on genetic background and other individual characteristics, will also bring benefits to healthcare systems, by working more effectively and keeping more patients out of hospital, thus reducing costs.

Personalised, or precision, medicine is already having a measurable impact on patient outcomes in Europe and the United States, leveraging genomics and broad data sets to move beyond the established one-size-fits-all model to more individualised care.

However, personalised medicine is still in infancy and, if it is to reach its full potential, it will require a far-reaching reconfiguration across the whole healthcare sector, from primary care and hospitals to diagnostics and pharmacies.

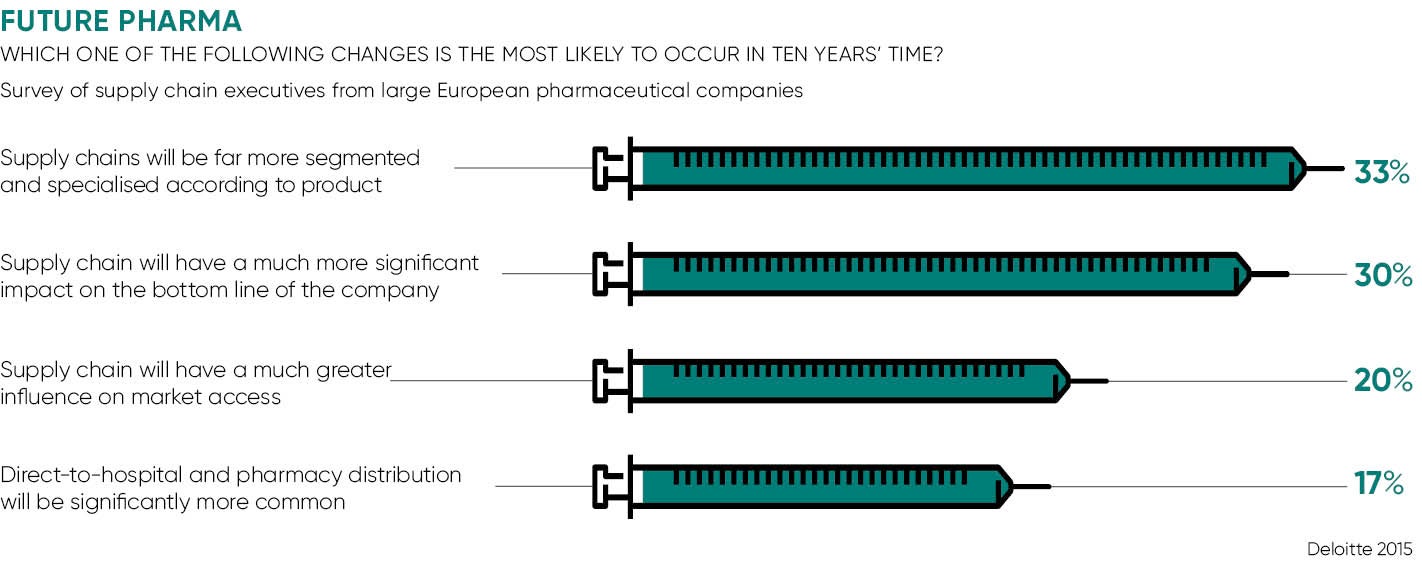

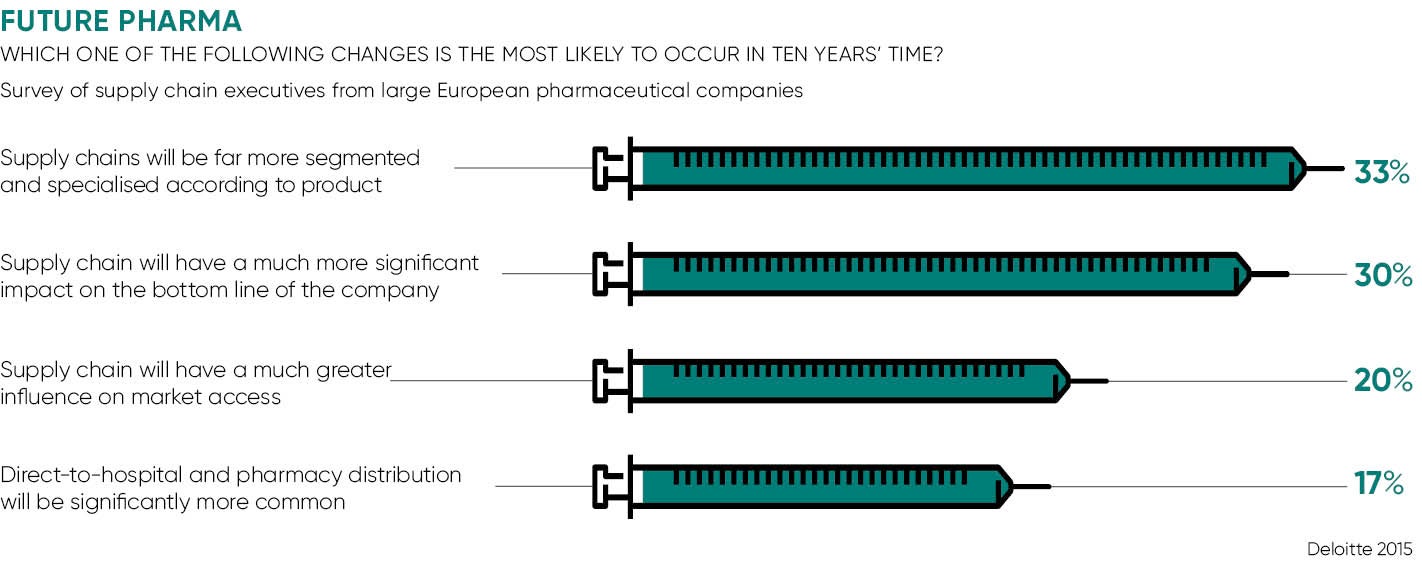

Impact on supply chain

The challenges are particularly urgent in the pharmaceuticals industry. Already buffeted by profound change, including the demise of blockbuster drugs and funding constraints in healthcare systems, big pharma must now face up to the structural reforms needed to deliver personalised medicine.

While attention has focused on the potential of personalised medicine to improve outcomes, the impact on manufacturing and the downstream supply chain may have been underestimated. Richard Archer, chairman of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Regenerative Medicine, has given warning that most of the existing manufacturing facilities and supply chain will be obsolete within a decade.

Precision medicine challenges many of the assumptions held by the pharmaceuticals industry for many years. In essence, the model that has served well for so many years is based on the development of a small number of big-selling drugs, each one capable of treating large numbers of patients. These are manufactured on an industrial scale and often stored in warehouses for months or even years before they are delivered, with little regard for efficiency of inventory.

Drug development itself is a costly and highly inefficient business, with many products failing at the trial stage. But the expense is cushioned by the substantial profits earned from the next blockbuster drug to hit the market.

The logistical transformation needed to speed up this latticework of sources and suppliers will pose a huge challenge

Personalised medicine requires a radically different model. As a starting point, it will hasten the demise of the blockbuster drug. Instead of producing a relatively small number of drugs that will sell in vast quantities across the world, tomorrow’s pharmaceutical manufacturer will be producing a large number of medicines for ever-smaller population groups. Instead of one drug for, say, breast cancer, a company will make a drug to treat the specific molecular and genetic make-up of a tumour and which will work for a small proportion of the population.

Practical implications

It is about much more than better matching of patients to existing products. In order to do this, manufacturing must be repurposed for a quantum increase in the number of products to be produced and distributed. Batch sizes will shrink, requiring the development of more nimble systems perhaps capable of making several different products that same day while maintaining control and integrity of each product.

Production schedules will need to become much more attuned to patient requirements. A vastly greater product range makes it much more difficult and expensive to maintain warehouses full of stock to be drawn down when it is needed. Personalised medicine will take the pharmaceutical industry much closer to the just-in-time schedules that have been embedded in many other industries for years.

So, future supply chains must adjust much more quickly with the right set of traceability capabilities to report on where the drugs went, who bought them and how they were purchased, if not on the individual level, then at least at the wholesale and pharmacy level.

Present pharmaceutical supply chains are simply not that flexible. Big pharma is global. The supply chains feature plants around the world, located on different continents from the compounds being used to create the drugs. Add to this the complexity of global distribution networks and we start to see that the logistical transformation needed to speed up this latticework of sources and suppliers will pose a huge challenge.

It also requires pharmaceutical companies to repurpose their relationship with the diagnostics that are an integral component of the personalised medicine paradigm. These diagnostics identify biomolecules used for disease prediction, risk assessment, diagnosis and prognosis. They can also identify genetic variations in individual patients that create susceptibility to adverse side effects.

But tests that identify genetic mutations and thus predict disease outcomes cannot be protected by patents. This could strangle the supply of novel diagnostic products essential for downstream processes that translate scientific innovation into the clinical tools which support the evolution of personalised medicine.

Increasingly, big pharma is likely to look beyond the industry for the expertise and processes it needs to reconfigure in readiness for personalised medicine. It requires a new vision to challenge an established way of thinking that has served the industry well for so many years, but those days look like being numbered. It is essential for the future of the pharmaceutical industry and for the sustainability of healthcare systems, as well as serving the best interests of patients.

Impact on supply chain