Unmanned ships piloted by people onshore or that sail and navigate the seas completely autonomously is a concept first floated in the 1970s, but one which is now close to becoming a reality.

An uptake in development and interest in the technology this year shows there is a real business case and demand for autonomous shipping.

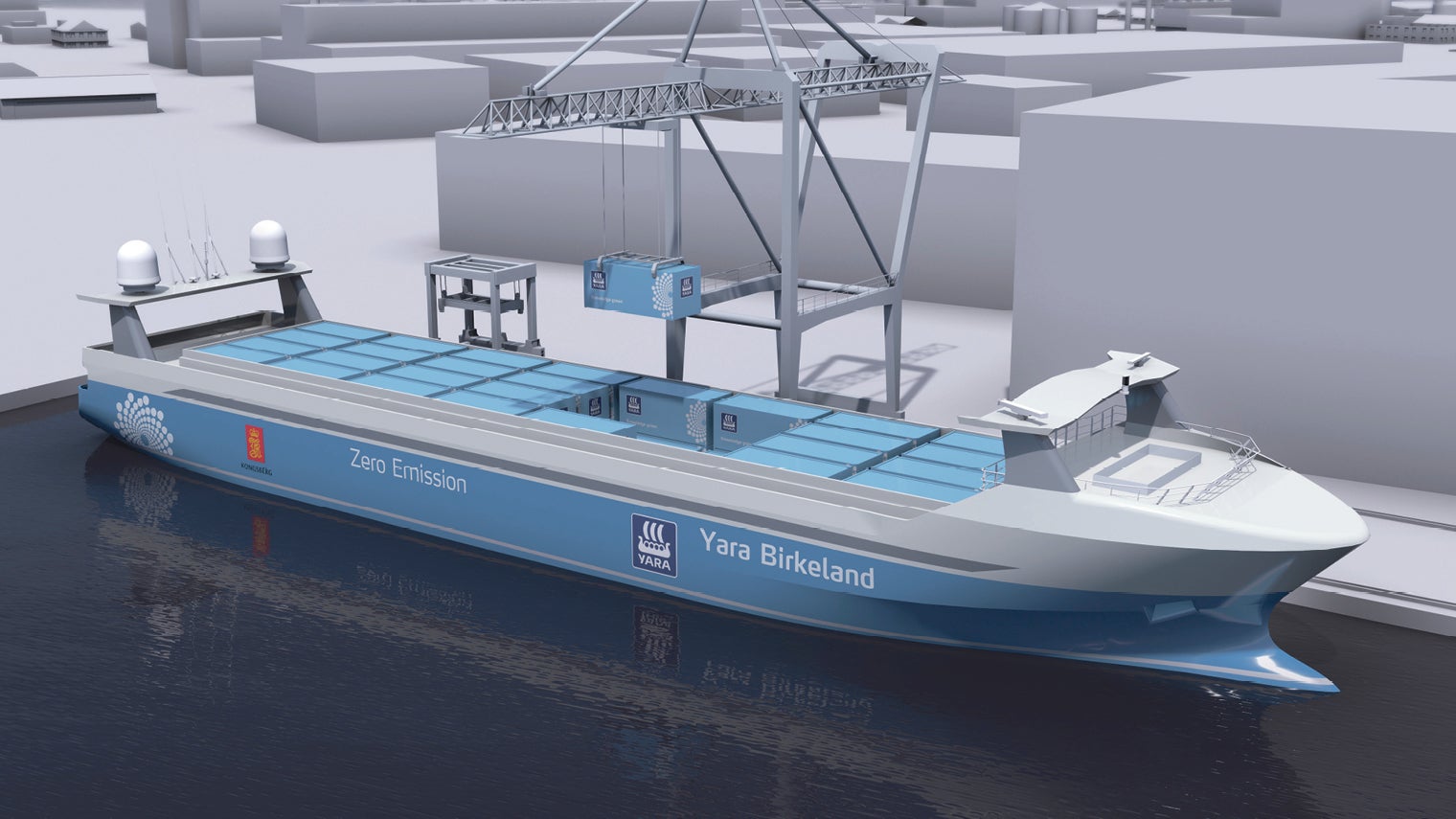

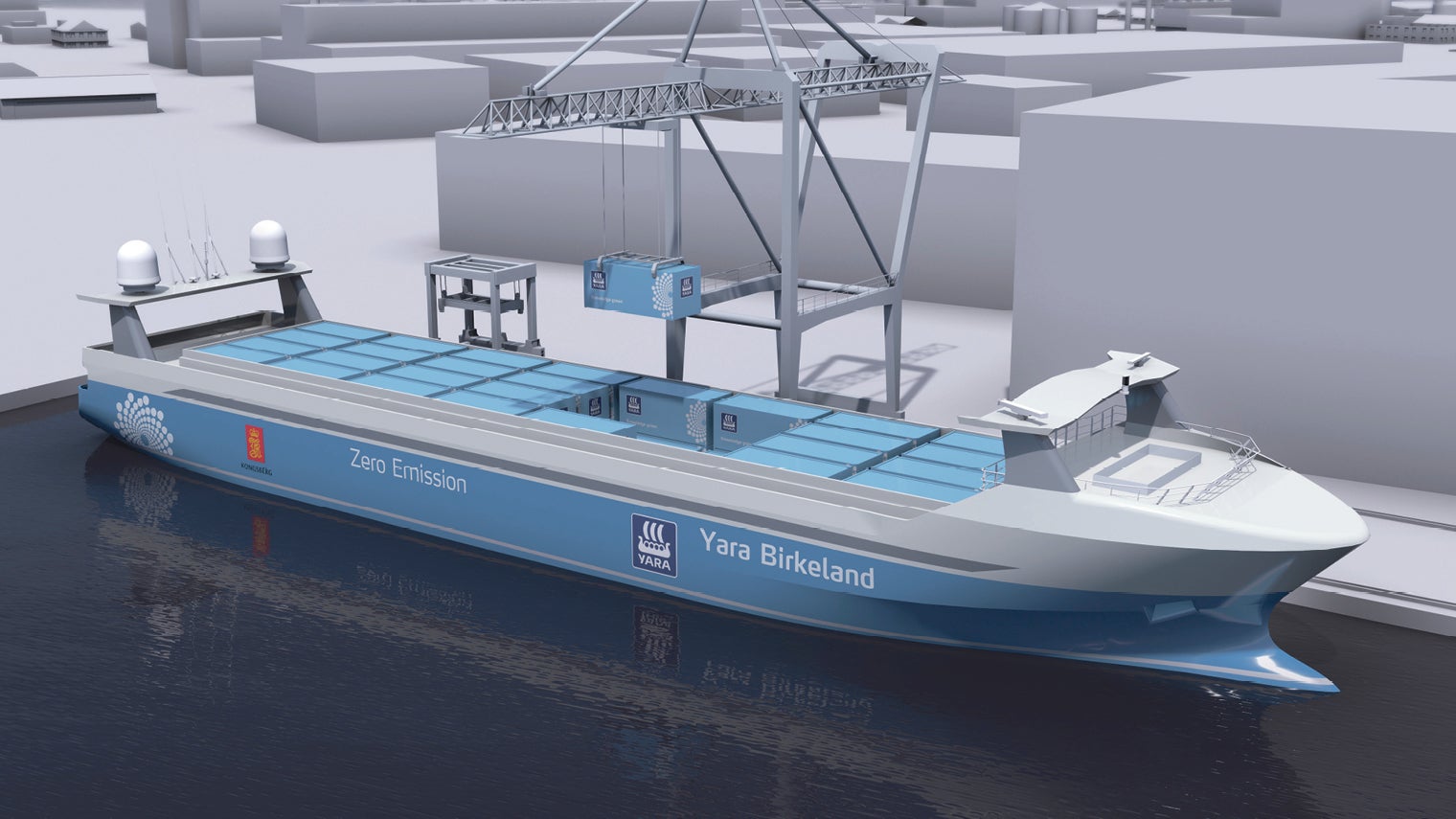

In May, Kongsberg and global fertiliser firm Yara announced the development of the world’s first fully electric and fully autonomous container ship, the Yara Birkeland, which will transport products from Yara’s Norwegian Porsgrunn production plant to Brevik and Larvik, also in Norway. The vessel’s launch is planned for early-2019.

Illustration of the Yara Birkeland, by Konsberg and Yara, expected to be delivered from the ship yard in early-2019

This June, Rolls-Royce and global towage operator Svitzer successfully demonstrated the world’s first remotely operated commercial vessel in Copenhagen harbour.

Furthermore, BHP Billiton, the world’s biggest mining company and shipper of one quarter of a billion tonnes of iron ore, coal and copper, this year said it intends to develop autonomous vessels to carry future cargo.

Unmanned shipping, like other automated technologies, offers several benefits to commercial operators, such as improved safety, cost reductions, more space for cargo and an overall more efficient marine supply chain, which could drive down costs for business heavily reliant on shipping.

“Remote-controlled and autonomous ships don’t get tired, they will reduce the risk of injury and even death, as well as the potential loss or damage of valuable assets,” says Oskar Levander, senior vice president, concepts and innovation, at Rolls-Royce.

According to a report by insurance company Allianz in 2012, between 75 and 96 per cent of marine accidents occur due to human error, mostly fatigue.

Furthermore, removing on-board crews can save freight shippers money by reducing personnel and construction costs because there is no need to build the facilities people require.

“When a ship sails autonomously you don’t have to worry about crewing costs, so you can have a much more sustainable sailing profile; you can sail short distances over a longer timeframe and use much less energy because you are not travelling full steam,” says Peter Due, director of autonomy at Kongsberg Maritime.

Another key driver for the technology is the potential to reduce emissions and save fuel costs in the long term. Autonomous ships will almost certainly need to be battery powered as there will be no one on board to provide the necessary maintenance fuel engines require.

The Yara Birkeland, for example, will be powered with electric battery propulsion that will reduce nitrogen oxide and carbon dioxide emissions, and improve road safety by ending the need for up to 40,000 truck journeys in populated urban areas.

The vessel will cost $25 million, about three times as much as a conventional ship of a similar size, but will save up to 90 per cent in annual operating costs by eliminating both fuel and crew, according to Yara.

However, the development of remotely controlled and autonomous shipping containers depends on the vessel’s ability to sense and understand what’s going on around it, and to communicate this, via satellite or other networks, to an onshore control room. It must also independently navigate, avoid collisions and perform complex manoeuvres.

Achieving these capabilities in ships is much harder than with autonomous cars

Achieving these capabilities in ships is much harder than with autonomous cars. “Sensors must be much tougher and more advanced than the sort required for an autonomous car and it’s important to consider to what degree there should be backup systems, because flying people out to fix a ship isn’t going to be cost effective,” says Øystein Engelhardtsen, senior researcher at DNV GL.

DNV GL has developed the ReVolt concept, a 60-metres-long, fully battery-powered autonomous ship for the short-sea transport segment that can alleviate issues of congestion in growing urban areas by taking trucks off the road.

In terms of physical security, unmanned ships would be safer than traditional vessels, as they can be built so it is difficult for pirates to board. The ship could even be remotely controlled to defend against intruders.

“The computers in command could immobilise the ship and without a captured crew to hold for ransom, piracy is significantly less valuable,” says Mr Levander.

On the flipside, anything that is remotely or computer controlled is vulnerable to cyberattacks, malfunction or control being lost due to communication failures. An out-of-control vessel, taken over by rouge agents, could be a deadly weapon if aimed at coastal cities.

Other barriers to autonomous shipping include advancing battery technology for longer-haul journeys, so the amount of batteries needed don’t take up most of the cargo space, and regulation, which is far behind the technology.

The European Union is currently assessing the feasibility of unmanned shipping. However, the rules for sailing in international waters are set by the International Maritime Organization, which has started to consider relevant regulation, but getting stakeholders to agree will be complex and no doubt long winded.

Steve Saxon, a Partner at McKinsey’s shipping and ports practice, believes the timeframe for international autonomous shipping could be around 2067. He cites cheap labour from India and the Philippines, cybersecurity and the need for on-board maintenance as disincentives, but points out that ports are already beginning to automate.

National shipping, from one part of a country to another, will be much easier to achieve than international routes and offers the immediate benefit of taking trucks off the roads. Norway, which is proactively pursuing autonomous shipping, is expected to be the first country to have national regulation.

Kongsberg Maritime’s Mr Due believes there will be a bi-lateral agreement between Norway and Sweden to sail autonomously between the two. However, crossing Norway to Denmark will be harder because there are international waters in between.

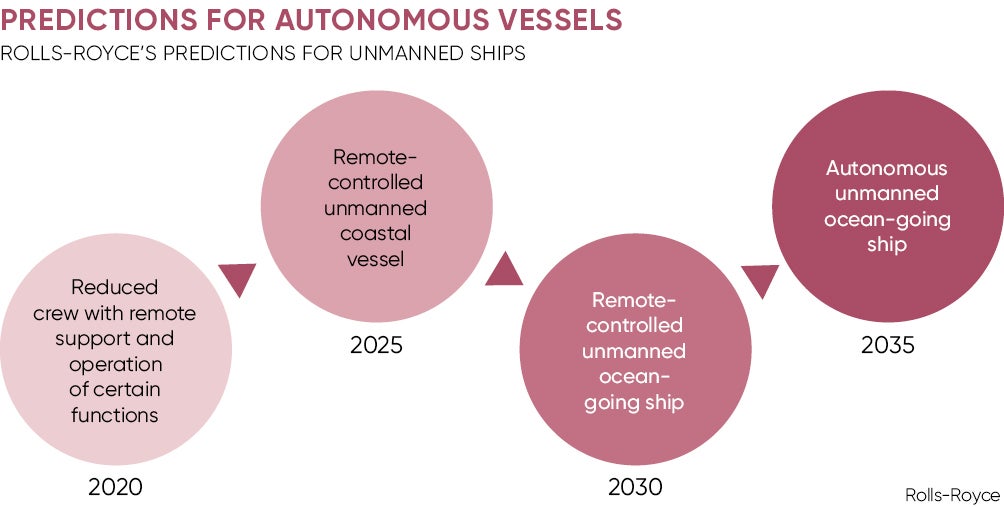

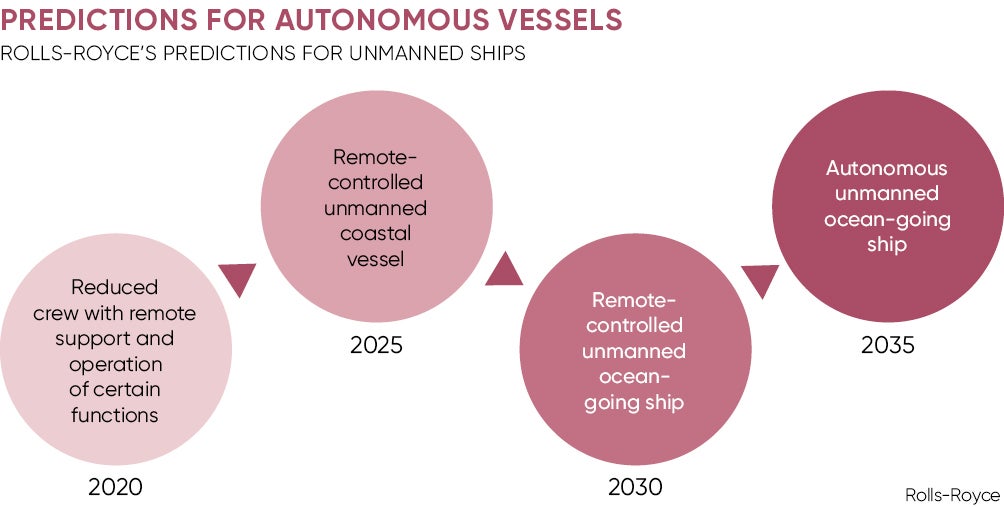

With the development of the Yara Birkeland underway, we could see autonomous ships operating in local waters as soon as 2020, with deals between neighbouring countries inked by 2025.