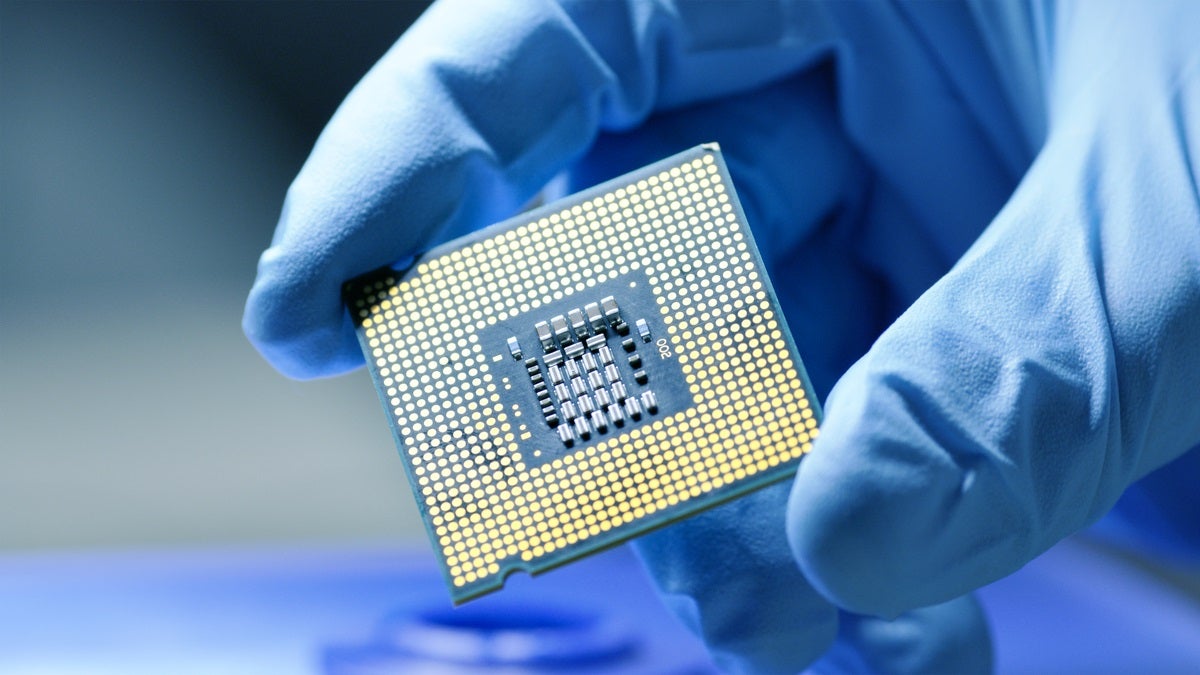

Inside millions of smartphones, laptops, household appliances and cars, small electrical components work tirelessly to power our everyday lives. However, there’s a problem as there aren’t enough of these components, known as semiconductors or, more commonly, chips, to go around and this is snarling up supply chains.

The global chip shortage started during the middle of last year when the coronavirus pandemic started to bite and car manufacturers saw sales slump, forcing them to put a brake on production. As the automotive industry is inherently focused on lean manufacturing and optimising supply chain costs by only ordering critical components when they’re needed, automakers paused the purchase of semiconductors. Chip factories then decided to redirect their focus towards the electronics industry which was experiencing unprecedented demand for consumer gadgets.

“The pandemic created the perfect storm,” says Sundar Kamak, head of manufacturing solutions at smart procurement company Ivalua, whose clients include white goods giant Whirlpool.

Although semiconductor supply will eventually catch up with market demand, there will be some short-term pain ahead

“On the one hand, it restricted free movement of goods, services and labour, limiting supply. At the same time, consumers had been locked down and this increased demand for home-entertainment systems and streaming devices.”

Kamak points out that, with chipmakers mostly based in Asia, it’s much easier for the semiconductor industry to supply the large number of gadget factories in the region than it is to ship parts to auto factories around the world.

When the automotive industry unexpectedly rebounded towards the end of last year, automakers suddenly found there weren’t enough chips available to fulfil orders and meet the demand for new vehicles. This stalled manufacturing further. In early-April, Ford and General Motors cut production at several plants across North America.

It’s a problem that could end up costing the global automotive industry $60.6 billion in lost revenue in 2021, according to AlixPartners. The consulting firm has indicated that the industry could shift between 1.5 million and 5 million fewer units this year than previously planned.

With the demand for consumer gadgets showing no signs of relenting, the electronics industry is now feeling the pinch as well. At Samsung’s annual general shareholders meeting in March, co-chief executive Koh Dong-Jin warned of a “serious imbalance”; the company has delayed the release of a new Galaxy Note mobile phone model. And Microsoft and Sony have seen supplies of their next-generation consoles limited in recent weeks.

Over-reliance on Taiwan

While there are many factors at play, given the complex nature of global supply chains, the chronic shortage of chips has been made worse by a heavy reliance on just a few chipmakers.

The behemoth of them all is Apple supplier Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which currently boasts a 56 per cent share of the chip foundry market. The chipmaker reported a 16.7 per cent year-over-year increase in revenue for the three months to the end of March.

Despite TSMC announcing in January that it would prioritise its production efforts to help the automotive industry ease its woes – it will also commit $100 billion over the next three years to increase its chip manufacturing capacity – there have been calls for global manufacturers to rethink their semiconductor sourcing strategies.

In the United States, President Joe Biden has pledged $50 billion to boost domestic chip manufacturing. And the European Union is seeking to achieve digital sovereignty and wants to become an independent chip producer that can supply its own demand.

Kamak says that such approaches would enable companies in America and the EU to “design near-shore strategies that would eliminate dependency on single-source vendors and reduce supply chain risks”.

Yet there will be no quick fix. “Although semiconductor supply will eventually catch up with market demand, there will be some short-term pain ahead,” says Gabriel Werner, vice president and Europe, Middle East and Africa solutions adviser at supply chain software provider Blue Yonder.

As demand continues to outstrip supply for the time being, the price of chips and other critical components could rise. Retail prices have remained largely unaffected, but Chinese gadget maker Xiaomi has conceded it may yet have to pass on some of the cost to its consumers.

Navigating future shortages

With the chip shortage likely to drag on for months to come, possibly well into 2022, the question is being asked how can manufacturers avoid similar snafus?

Automakers in particular are being encouraged to move away from the just-in-time model of manufacturing to a just-in-case one, stockpiling chips to hedge against future slowdowns. But this could create a “bullwhip” effect, says Werner.

“There is a risk that the semiconductor industry will overcompensate and then there will be too many chips in production,” he says, adding the industry has always been cyclical, typically peaking during the festive season.

Werner believes manufacturers should be doubling down on their efforts to gain insight into their supply chains so they’re able to respond to sudden shifts in demand more effectively.

“Instead of relying on traditional methods to predict consumer demand, manufacturers need to explore the use of artificial intelligence to give the visibility and flexibility needed to adapt to changes,” he argues. “Speed, real-time visibility and automation have become the defining themes for effective supply chain management. Those that are able to build robust supply chains will have a better chance of dealing with future disruption.”

Kamak agrees: “Companies that have risk monitoring capabilities in place are definitely able to fare better against critical supply shortages.”

Inside millions of smartphones, laptops, household appliances and cars, small electrical components work tirelessly to power our everyday lives. However, there’s a problem as there aren’t enough of these components, known as semiconductors or, more commonly, chips, to go around and this is snarling up supply chains.

The global chip shortage started during the middle of last year when the coronavirus pandemic started to bite and car manufacturers saw sales slump, forcing them to put a brake on production. As the automotive industry is inherently focused on lean manufacturing and optimising supply chain costs by only ordering critical components when they’re needed, automakers paused the purchase of semiconductors. Chip factories then decided to redirect their focus towards the electronics industry which was experiencing unprecedented demand for consumer gadgets.

“The pandemic created the perfect storm,” says Sundar Kamak, head of manufacturing solutions at smart procurement company Ivalua, whose clients include white goods giant Whirlpool.