World leaders should be preparing about now to head to Glasgow for the United Nations annual climate summit. But with the event pushed back a year amid the coronavirus pandemic, their attention lies elsewhere.

Regardless, two facts remain unchanged. First, climate change is not going away. Global temperatures could reach catastrophic levels if emissions are not cut annually by 7.6 per cent up to 2030, the UN warns. Come next year, the warning will still stand.

Second, when government leaders do eventually meet in Glasgow, expect business leaders to be out in force. Once the preserve of policymakers and campaigners, high-profile climate activists now include sharp-suited executives. So why the shift? And what exactly are companies hoping to gain from hobnobbing on climate policy?

Taking a bold, public stance on climate change

Part of it, of course, is being seen to act. Businesses are under pressure on all sides, from consumers at the till, recruits during interviews, investors at their annual meetings and so on, to show their commitment to climate action.

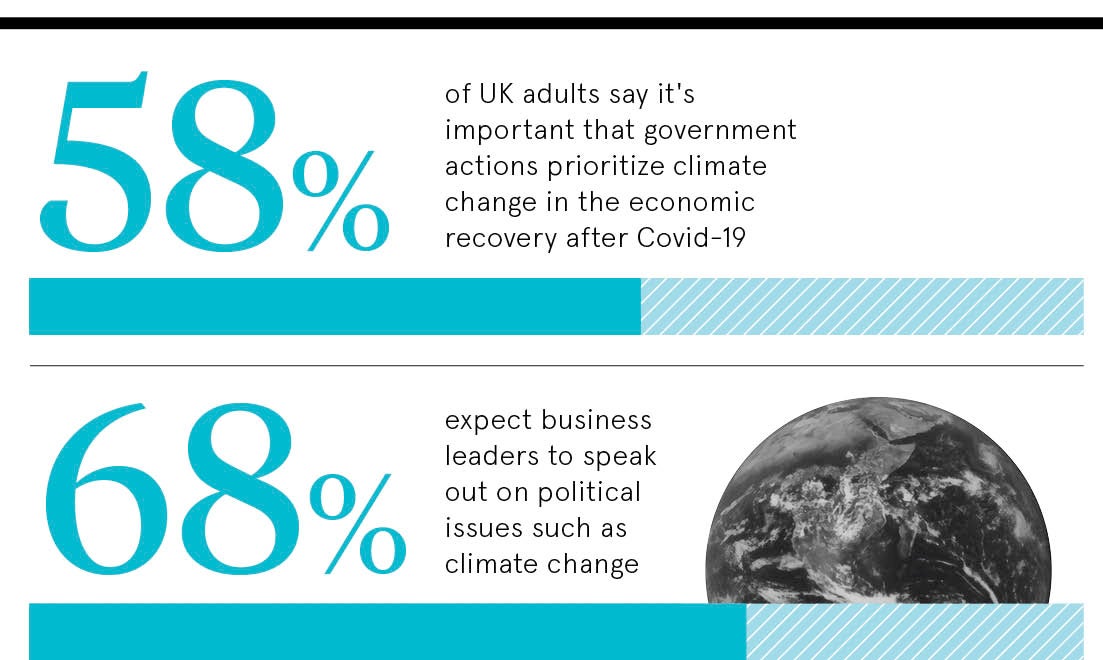

According to new research from Ipsos MORI, for example, seven in ten (68 per cent) UK adults now expect business leaders to speak out on political issues such as climate change.

Global climate summits provide an ideal stage for such a demonstration. Take this year’s New York Climate Week. The online event sparked a deluge of corporate announcements, from Walmart’s goal of net-zero emissions through to PepsiCo’s pledge to switch to 100 per cent renewable energy.

Eye-catching as these headline splashes are, they hide a subtler and arguably more substantial corporate contribution to climate action of encouraging policymakers to think ambitiously and act boldly.

If that sounds counterintuitive, then no surprise. International business associations, especially those bankrolled by the fossil fuel industry, stand as a watchword in climate circles for obfuscation and delay.

Powerful as these lobby groups certainly are, however, their voice is not universal. Opposing business voices that favour more aggressive climate action not only exist, but they are also increasingly impatient to be heard.

A recent case in point is the open letter sent by 185 chief executives to European government leaders expressing their support for the European Union’s Green Deal recovery package.

The letter, which includes the likes of Unilever, EDF, Google and IKEA among its signatories, explicitly encourages European legislators to set tougher EU climate norms, such as increasing its 2030 emissions reduction target from 45 to 55 per cent.

Climate action needs all businesses to get involved

Why? Partly for reasons of competitive advantage. Companies that have invested in energy-saving technologies, clean power and other emission-reduction measures want the laggards in their industry to follow suit.

As importantly, if not more, however, is the fact that climate change is a profoundly systemic problem. A real estate operator can become 100 per cent carbon neutral, but it won’t stop sea levels rising and washing away its coastline condos.

Systemic problems can only be solved through systemic solutions, says Karl Vella, international climate policy manager at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

“For that reason, we’re not seeing leading companies talk about their business or sector in isolation, but instead they focus their advocacy on the context of their industry in wider systems,” he says.

Embracing the rise of corporate lobbying

For companies genuinely committed to climate action, progressive advocacy represents the logical next step once they have exhausted all possibilities for emissions reduction within their immediate operations.

Mike Peirce, corporate partnerships director at The Climate Group, a network of companies committed to climate action, gives the example of the UK Electric Fleets Coalition. Founded in conjunction with telecoms company BT Group, the initiative seeks to work with the government to create a policy environment conducive to 100 per cent electric vehicle sales by 2030.

“To decarbonise the transport sector, we need more electric vehicles on the road, which requires a push from government as well as individual businesses,” says Peirce.

The coalition’s approach is what might be described as “lobbying light”. BT and its fellow fleet operators hope that by greening their own fleets, policymakers will see the signal from the market and be encouraged to act; what is often referred as an “ambition loop”.

In other cases, corporate advocacy is more on the nose. In May, for example, the non-profit environmental group Ceres mobilised more than 300 US corporations to call on lawmakers to introduce a mandatory carbon price for business.

Such unilateral measures help create a level playing field, participating companies argue, as well as providing some clarity of policy that in turn gives business the confidence to invest in long-term climate solutions.

Companies need to practise how they preach

Given the chequered history of corporate environmental lobbying, eyebrows might rightly be raised at the idea of businesses influencing future climate policy, however progressive their alleged motives.

As a basic minimum, companies engaged in such advocacy need to ensure their own policies and practices line up with their public positioning.

Nothing is more likely to engender distrust among policymakers and the public than a dissonance between words and action, warns Jen Austin, policy director for a UN-backed team of climate action champions linked to next year’s Glasgow summit.

“It’s imperative that companies’ internal climate targets and ambitions are consistent with what they are saying in public or behind closed doors to policymakers,” she says.

The injunction extends to corporate links to industry associations. The advice from We Mean Business, a coalition promoting climate action, is for companies to first work with like-minded members to engage the lobby groups to which they belong.

If that doesn’t work and policy anomalies still persist, then pro-climate firms should seriously consider jointly renouncing their membership and leaving as one, says the organisation’s chief executive María Mendiluce.

The arrival of a progressive business voice marks a welcome counterbalance to the persistent lobbying of corporate naysayers. The more who follow their lead, the louder their voice will become and, hopefully, the bolder climate policy will be.