For nearly 15 years, Professor Nigel Halford has been trying to improve wheat. When wheat is cooked, it forms acrylamide, a carcinogenic chemical. Food producers in Europe are required to keep acrylamide content below acceptable levels, although researchers still don’t know whether burnt toast poses a threat to human health. Either way, Professor Halford, a crop scientist at UK non-profit Rothamsted Research, believes wheat is in need of an upgrade and that means reducing the potential for acrylamide to form.

You end up with a plant that’s identical to the plant you started with, but it has one small change

Professor Halford and his team have tried various tactics since embarking on the project in 2004, but in the last couple of years have been employing a new approach. CRISPR is a pioneering gene-editing tool which enables scientists to make precise changes to an organism’s DNA. Typically, researchers might remove part of the genetic code responsible for an undesired characteristic. In wheat, it’s believed that high levels of acrylamide production can be linked to a specific gene. “We’re trying to knock that out,” says Professor Halford.

CRISPR gene editing technology could transform food production

CRISPR gene editing has only been possible for six years, but the technology has already shown the potential to transform the world’s food supply. Safer wheat is just one possibility. Gene editing could create crops that stay fresh longer and are resistant to disease, insects and extreme environments.

It has been used to develop mushrooms that don’t bruise, high-yielding corn and soybeans packed with healthy oils. Traits like these could be achieved using traditional plant breeding or existing biotechnology, but Dr Tina Barsby, chief executive at crop science company NIAB, says: “Gene editing is so much faster. Years faster. When you’re talking about feeding the world, that’s important.”

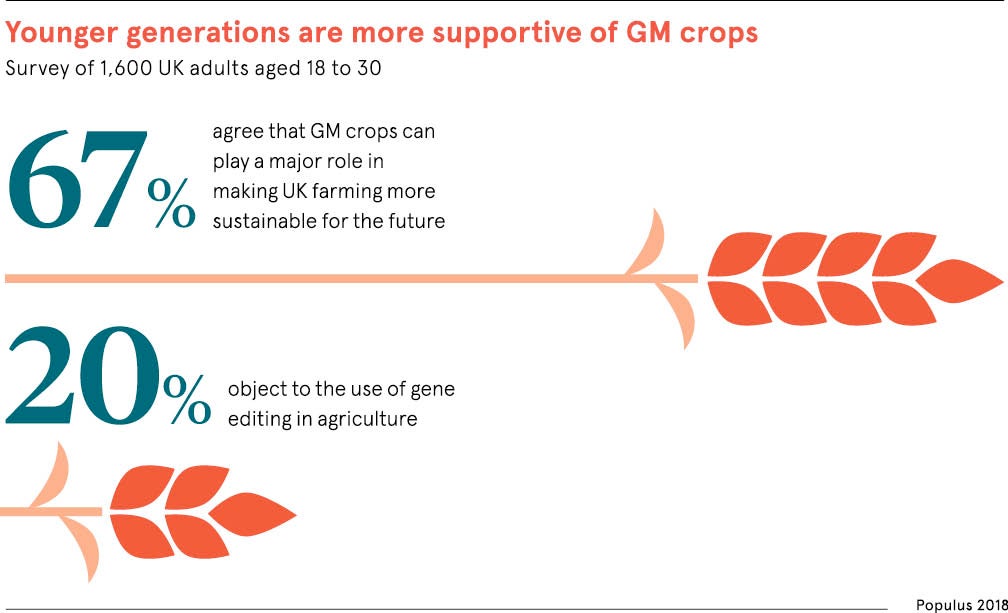

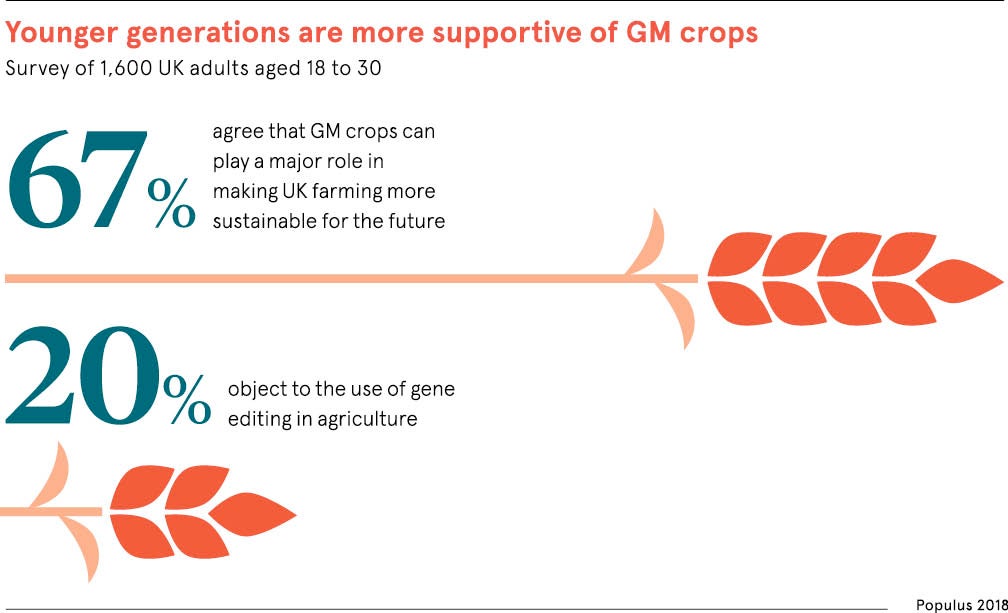

Of course, genetically modified food promised similar benefits when it came to the market almost 25 years ago. Then came the panic over so-called “frankenfoods”, a public backlash and the introduction of strict regulation in markets including the European Union.

Gene editing is a different proposition. Professor Wendy Harwood, senior scientist at the John Innes Centre research institute, who is working to develop drought-resistant barley, says: “The value of gene editing is the precision, but also the range of things you can do.”

EU ruling chooses to class gene-edited foods as GMO

Unlike genetic modification, which typically involves inserting foreign DNA into an organism’s genetic code, scientists say gene editing is largely used to speed up the natural breeding process. “You end up with a plant that’s identical to the plant you started with, but it has one small change,” says Professor Harwood. “The same thing could have happened naturally.”

However, hopes that gene editing might herald a new dawn in the field of crop science were dealt a blow in July when the European Court of Justice ruled that gene-edited products should be treated as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and subject to stringent regulation that predates the CRISPR technology. While laboratory work will be largely unaffected, researchers say the ruling will make it almost impossible for European companies to bring gene-edited foods to market.

For Professor Halford, who hopes one day to see low-acrylamide wheat products on sale to consumers, “it was a hit in the head”, he says. While European politicians could still decide to amend GMO regulations to exclude gene-edited crops, some experts in the field believe negative public perceptions of crop science makes such a scenario unlikely.

Professor Huw Dylan Jones, chair in translational genomics for plant breeding, at Aberystwyth University, says: “There aren’t that many votes in support of biotechnology. It’s easier to keep your mouth shut.”

Other countries around the world embracing gene editing for food

If the ruling stands, it will put the EU out of step with other markets around the world. In Canada, crops are regulated on the basis of the traits present within them rather than the method used to produce them. Argentina, China and the United States have all adopted a light-touch regulatory approach to gene editing.

In March, the US Department of Agriculture said gene-editing tools would not be regulated, while noting “they can introduce new plant traits more quickly and precisely, potentially saving years or even decades in bringing needed new varieties to farmers”.

Major biotech firms including Monsanto, Syngenta and DuPont Pioneer are all investing heavily in gene-editing technology and this investment is being focused in markets where there are fewer regulatory hurdles to innovation.

Syngenta says its gene-editing research is largely taking place in China and the US. “We naturally chose to co-locate our main research resources in genome editing in those countries which are supportive of seeds technologies, and consequently host the main weight of leading academic organisations and companies working in the area,” the company says.

In the US, smaller firms such as Benson Hill Biosystems and Cibus have also entered the market and are developing products including more resilient cacao trees and disease-resistant rice.

Crop scientist at Rothamstead Research

EU ruling will hold Europe back from vital food innovation

Stefan Jansson, head of plant physiology at Umeå University in Sweden, says this kind of innovation is now unlikely to happen in Europe. “Anyone who is really trying to help the world and make plants that are better suited for unfavourable conditions will have problems because now they can’t commercialise their products,” he says.

Producers in the US are racing to bring a gene-edited soybean to the commercial market. Meanwhile, the future for gene-edited foods in Europe looks doubtful. Professor Halford believes he is close to producing an improved variety of wheat, but this achievement will be tarnished. “We won’t be able to do anything with it,” he says.

In the UK, the fate of gene-edited foods appears to have been decided before most consumers have even heard of the technology. “They won’t get the choice,” Professor Halford laments.

CRISPR gene editing technology could transform food production