The UK’s energy grid has been powered for decades by coal and nuclear plants. As these centralised power stations, designed to deliver large quantities of electricity across hundreds of miles of national power networks, are gradually shut down, they are being replaced with smaller, nimbler, decentralised sources of energy.

The benefits of decentralisation – drawing power from multiple, localised energy networks – are numerous. Deploying local solar plants, small wind farms, battery storage and combined heat-and-power plants can drive competition up, and power prices down, as the number of energy providers increases.

It enables greater control in communities over the sources of the energy they consume. Consumers can sell power back to the grid, offering revenue opportunities and a way to provide backup power to the national grid. Localised power is often renewable, helping cut carbon emissions, too.

How close are we to a decentralised energy grid?

However, the UK is a long way from having a decentralised energy grid. Tim Rotheray, director of the Association for Decentralised Energy, says this is because the scale of the change needed is huge. Achieving a decentralised energy grid means turning decades of UK power policy and development on its head, and adopting exactly the opposite approach.

“This is the nub: the UK’s electricity system was designed around big bits of kit,” says Dr Rotheray. “In the 1970s and 1980s, the way you drove down the price of energy was by economy of scale. These plants were, and are, all trading huge amounts of electricity.”

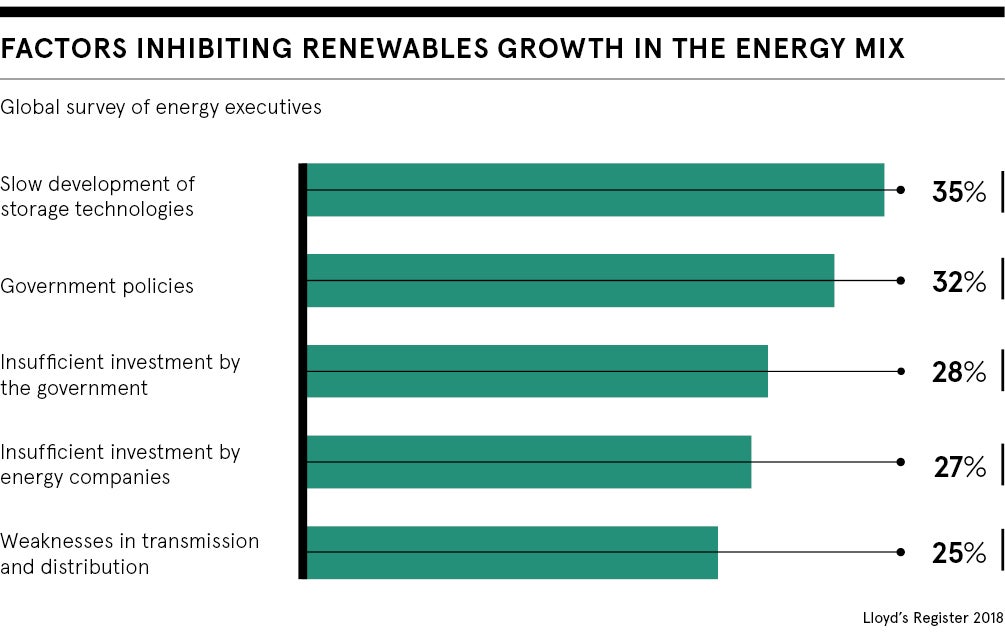

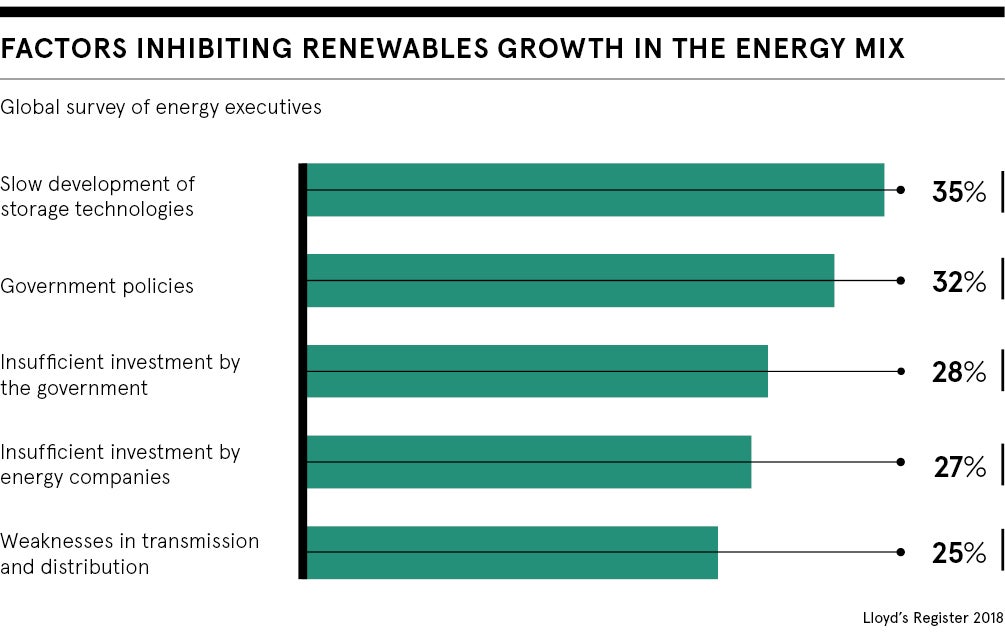

Times have changed and the economics of small-scale, localised power have vastly improved. Prices for renewable technologies have dropped dramatically over the past decade and last year business services firm Lloyd’s Register said it expects decentralised renewable energy to be cheaper than power from the grid by 2025. To remain ahead of the curve, policymakers and the energy industry need to start bringing their former customers, and new competitors, into their policy conversations.

“Policy is still created in the traditional system and that’s an absolutely huge barrier to growth of the decentralisation model,” says Dr Rotheray. Historically, energy policy was developed “by energy experts talking to energy experts, but now power market participants include brewers or bakers or steel fabricators; their participation is vital to achieve the growth and the security of supply the country needs”.

Government need to adopted holistic approach to energy supply

Dr Rotheray warns expansion of decentralised energy grids will be further stymied if it causes any inconvenience to the public. “The system is shifting from the traditional siloed, centralised system and it has to. But as an energy consumer, you don’t want to experience these [changes]. You’re interested in remaining warm and powered,” he says. For the decision-makers involved in the transition, “it’s about starting to see the energy system from that perspective”.

The government also needs to adopt a more holistic, joined-up attitude when it comes to looking at the UK’s energy future in general, he says. New and upcoming green energy auctions, for example, procure future UK power from low-carbon sources such as offshore wind. As the lowest bids win, it is typically big-hitter developers and investors with large-scale projects that are winning these contracts.

The auctions replaced subsidies, which Dr Rotheray says were key to the development of localised power. “Those policies were very successful at the local level, on a small scale. They overcame barriers for consumers to participating in the energy system. Instead of asking people to engage in the wholesale power market, they were just paid a set fee for whatever power they put into the grid,” he says. As these subsidies are phased out and replaced by auctions, won by international utilities and financiers, “the challenge of the next decade is to unlock local access”.

How the decentralised grid is working in other countries

Other countries are already adapting to the challenge posed by decentralisation. Dr Rotheray points to the Nordics’ Nord Pool power market, and individual states and energy firms in the United States, as examples of flexible, modern power grids. In America, consumers are increasingly being rewarded with rebates for modifying their behaviour, for example switching on air conditioning at times when the grid is less stressed, and are seeing cost-saving benefits more quickly than their UK counterparts, he says.

Could the UK eventually have a fully decentralised energy grid? Dr Rotheray says perhaps this is the wrong question to ask. It’s more important that the UK’s electricity ecosystem is fit for purpose. He concludes: “We need to ensure that the power system is low carbon and secure. It should be open to every possible participant. Then the market will find its own level, whether that’s centralised energy, local energy or a mix.”