It may have seemed like a normal wet, blustery autumnal day to most of us, but for the UK’s offshore wind industry, November 28, 2018 was a red letter day. Storm Diana was buffeting the country, sending wind turbines into overdrive, so that during one 30-minute period, wind farms contributed a third of the UK’s electricity for the first time.

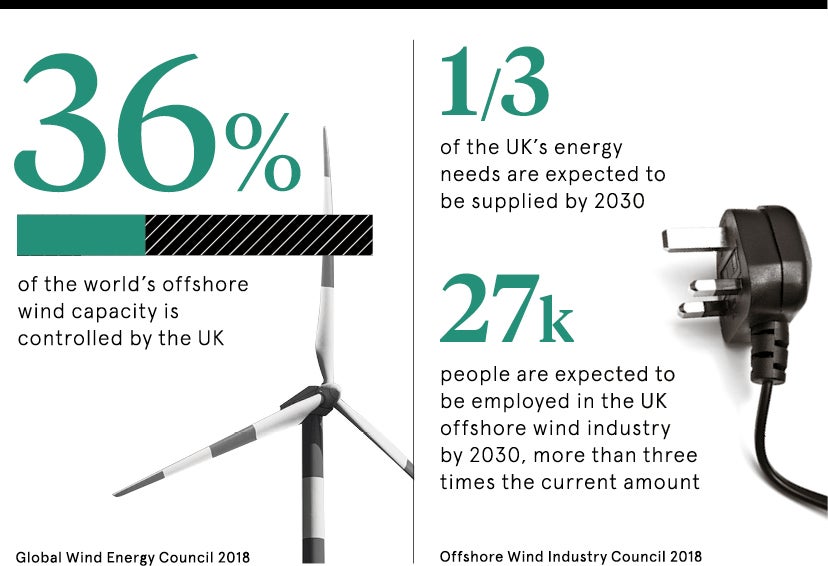

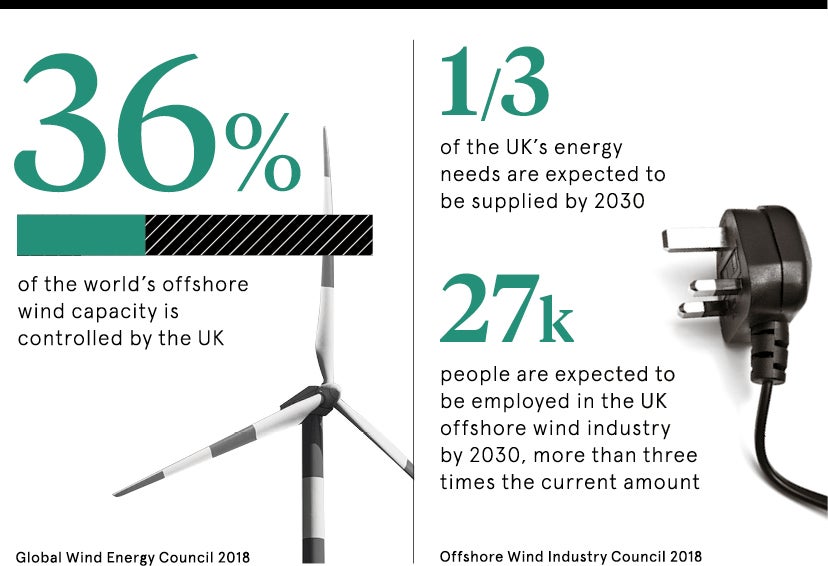

It was an important milestone in the sector’s journey towards regularly supplying a third of the nation’s energy needs by 2030, with an installed offshore wind capacity of 30 gigawatts (GW) – according to last year’s sector deal with the government – compared with 8GW today.

“Offshore wind is well placed to be the backbone of Britain’s electricity system,” says Benj Sykes, vice president and UK country manager at Ørsted, especially with the retirement of coal and nuclear generation. “We’ve seen a dramatic drop in the cost of electricity from offshore wind that makes it one of the lowest-cost ways to decarbonise.”

What has contributed to the rise of offshore wind?

Over the last three years, as the industry has scaled up, the price of offshore electricity has halved. While the first turbines produced less than a megawatt each, today’s churn out closer to ten, says Stephen Wyatt, research and innovation director at the UK’s Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult, with a new wind turbine now installed in British waters at the rate of one a day.

“Deployment has been key,” says Stephen Bull, senior vice president for wind and low-energy solutions at Equinor. “The more turbines you push out, the more innovation that’s driven, the larger the turbines get, the more you’ll see economies of scale.” It’s a rate of growth that is creating jobs and by 2030 the industry expects to employ 27,000 people, more than three times the present figure.

The sector has benefited from a long-term commitment by successive governments, says Mr Sykes who, in his role as co-chair of the Offshore Wind Industry Council, is helping to broker a sector deal with Whitehall. This is likely to include a commitment to continue to grow offshore wind at the rate of 2GW a year, so it is easier for developers and wind turbine manufacturers to make the necessary investment.

“Like all parts of the energy sector, we have to think over the long term; we can’t think in terms of four or five-year parliamentary cycles,” he says.

The process used to award wind farm contracts has also helped make offshore energy cheaper. It begins with the release of suitable areas of seabed by the Crown Estates, passes through a long period – often taking several years – of research and consultation, before culminating in a government auction and the award of a contract for difference (CFD).

“The large utility companies that are developing these offshore wind projects have to bid in really low to be sure they are going to get a wind farm project,” says Dr Wyatt. “It’s this system that has helped to drive costs down.”

Looking forward to new innovations in offshore wind

But there is a sweetener as the CFD ensures developers receive a fixed price per megawatt hour which, says Mr Sykes, takes away a lot of the risk and has enabled companies to explore new forms of finance. For instance, Ørsted has brought in institutional money and pension funds to invest in Hornsea 1 and 2 in the North Sea, the biggest wind farms under construction in the world. Between them they will generate 2.5GW. “That’s capacity comparable to a nuclear power station,” he adds.

Dogger Bank, a huge sand bar in the North Sea, may be more famous for trawlers than turbines, but it’s also set to become the new frontier for offshore wind in the UK. In partnership with SSE, Equinor is developing three of the four current sites (German energy company innogy is progressing the fourth) with more zones to be released over coming years.

Located nearly 200 kilometres off the coast of Yorkshire, once completed the four wind farms will have a total generating capacity of 4.8GW. “This really could be the new electricity hub for the North Sea,” says Mr Bull.

But while the site is further offshore than the industry has ever ventured before, explains Dr Wyatt, because it is so far from land, wind speeds are higher, while at 30 metres the sea is relatively shallow, making installation of the turbines easier.

UK is number one in offshore wind, but for how much longer?

The wind farms are likely to be the most technical and innovative ever built, and include the use of robotics and autonomous systems, digital twins, so engineers can conduct virtual walk-rounds of the site, and predictive maintenance.

Globally the UK now controls just under 40 per cent of the world’s offshore wind capacity, according to the Global Wind Energy Council, but with the likes of China, America and South Korea ramping up their own interests, it’s unlikely Britain will hold its number-one status for long.

This shouldn’t be seen as a problem, says Dr Wyatt. “Using our experience, our know-how and our established supply chains is absolutely key for these other countries to come down the ‘cost curve’ as well, and make offshore wind as economical as it is here.“In terms of first-mover advantage, for all the learnings, all the experience and a lot of the supply chain companies, we’re in a great position.”

UK businesses are already exporting to wind farms all over the world, Mr Sykes adds, and by 2030 the industry hopes to have increased exports of goods and services fivefold to £2.6 billion, from £0.5 billion in 2017, according to the Offshore Wind Industry Council.

“It’s the cutting-edge technology that will be most exportable, whether that’s robotics, whether that’s drone technology, whether that’s smart systems and big data,” he says.

“I’m absolutely convinced offshore wind can be the next exportable success story for UK plc.”

What has contributed to the rise of offshore wind?