It would be big news for any country to invest $50 billion in renewable energy to generate 10 gigawatts of wind and solar power by 2023. However, when the nation concerned is Saudi Arabia – the Gulf State that possesses nearly one fifth of the planet’s proven reserves of petroleum and ranks as the largest global exporter – the story takes on another dimension.

It should not, though, come as such a surprise. In the era of the grand energy transition, we have entered a world where renewable is now the new normal and, to some extent, we have Paris to thank for that.

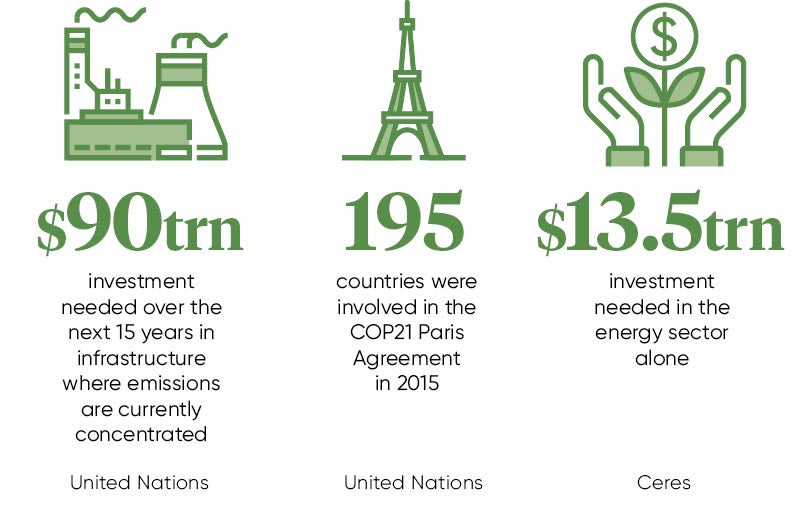

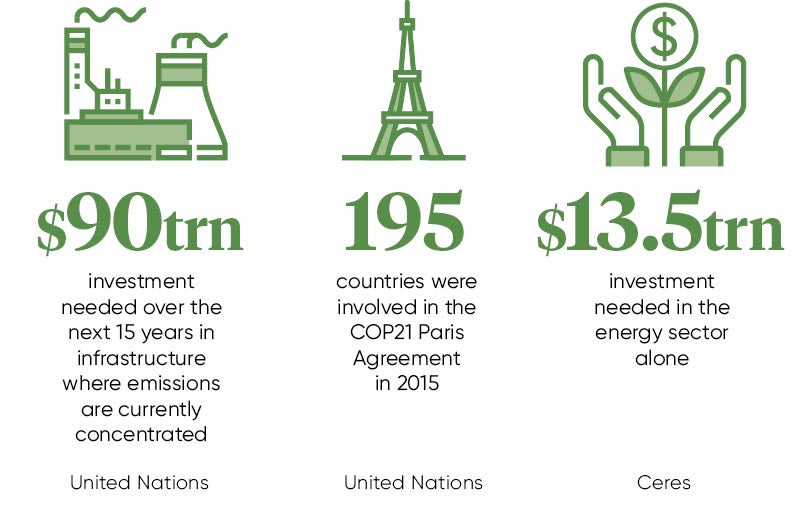

Much has happened since 195 countries adopted the first universal, legally binding climate deal to limit global warming below 2C, as signatories to the COP21 Paris Agreement, 2015. The normalising effects are far reaching, says Michael Liebreich, founder of Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

“Perhaps the biggest impact of the Paris Agreement is that the shift to a low-carbon economy is now seen as inevitable over some extended timeframe, not pie in the sky,” he says.

“So now, completely mainstream investors are asking companies about climate risk and stranded fossil assets. And in industry after industry, right through the supply chain, it is clear a lower environmental or climate impact can be a source of competitive advantage, driving a surge of innovation.”

There is resilience to this shared vision for renewables and upwards trajectory, despite Brexit and President Trump, observes Damian Ryan, acting chief executive of The Climate Group. “We’re not seeing any evidence of business losing confidence. In fact, businesses recognise the need to be more vocal in their support for climate action in light of political instability. They know signalling their intent to use renewable power sends a strong message to policymakers,” he says.

Business energy consumption

To date, almost 700 businesses and investors have made climate commitments through the umbrella coalition We Mean Business, where they can sign up to sourcing 100 per cent renewables (RE100) and doubling energy productivity (EP100).

Collectively, such corporate commitments are already achieving volumes at country-scale, says Frances Way, co-chief operating officer at CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project), working in partnership with The Climate Group on RE100. “Business learns fast. We are working with 87 companies committed to 100 per cent renewable power; together they are creating demand for approximately 107 terawatt-hours annually, around the same amount of electricity as consumed by The Netherlands,” she says.

Perhaps the biggest impact of the Paris Agreement is that the shift to a low-carbon economy is now seen as inevitable over some extended timeframe, not pie in the sky

Numbers are big and names impressive. CDP has identified 613 corporations, such as Anglo American, Bank of America, Delta Air Lines, Iberdrola SA and Johnson Controls, which are all factoring Paris into their business plans. They boast combined market capitalisation of $12 trillion.

More strategic approaches also see companies setting science-based emissions targets, integrating carbon pricing and tackling impacts downstream. Ms Way adds: “Supply chains are responsible for up to four times the greenhouse gases of direct operations and therefore present ample opportunity to lower emissions.”

No fewer than 89 of the world’s largest purchasers, including BMW, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft and Walmart, are engaging their suppliers through CDP, wielding purchasing power of $2.7 trillion, equivalent to the entire UK economy. Supplier emissions savings of 434 million tonnes were disclosed in 2016, more than the annual total of France.

Being responsible

With big impact, however, comes big responsibility. Human rights concerns and associated reputational risk may become more of an issue for renewable energy, argues Phil Bloomer, executive director of the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC).

“The Paris Agreement clearly placed the future of energy in the hands of renewables, but we need a transition to a low-carbon economy that is not only fast, but also fair. As demand increases for energy from land-intensive wind, solar and hydropower projects, firms cannot afford to overlook poor communities who depend on that land for life and livelihood,” he says.

When BHRRC surveyed renewable energy companies on human rights and community engagement, they found an alarming lack of transparency, awareness and implementation.

To imagine the future of energy, though, as merely a face-off between fossil fuels and renewables for market share, would be to underestimate the breadth and depth of technological change. Disruptors come in many guises.

January witnessed the San Francisco launch of an innovative utility-driven clean-energy incubator, called Free Electrons. What differentiates this particular offering is its market muscle. As a consortium of leading utilities, it covers more than 40 countries, with $148 billion in net income and 73 million end-customers worldwide.

According to programme manager Hendrik Tiesinga, partners are preparing for the future and reinventing themselves in the process. “The utilities come from very different frameworks and markets, yet see themselves faced with the same challenges of deregulation, rapid adoption of renewables, the internet of things and digitisation of energy. They are more worried about the next startup from Silicon Valley, than Trump or Brexit,” he says.

Reinvention has ramifications. New priorities call for new practices plus new people, argues Graeme Edge, co-founder of Calgary-based executive search firm McLaren Chase, and chief instigator of energy disruptors. He says: “Oil and gas companies have an abundance of technical talent. However, the energy company of the future will be increasingly digitized, marrying hard engineering with software skills.”

As the industrial internet of things (IIoT) rolls out, Mr Edge predicts fresh faces in the C-suite.

“We are going to see larger exploration and production companies start to retool their boards and executive teams with greater emphasis on former manufacturing and technology leaders. Another key area will be big data analysis and management skills. It will be essential to have a well-developed IIoT strategy and associated talent,” he says.

Post-Paris, therefore, the power game is not only becoming decarbonised, but increasingly digitised and disrupted, too. The future of energy might be many things, but it won’t be dull.

Business energy consumption