Redistribution of resources and roles in the public sector demands that organisations increase productivity, meet key performance indicators and be more connected to the consumers while delivering higher-quality services.

Digital transformation is driving change from digitisation which bolts new technology onto old processes, towards a comprehensive revision of policies, processes and services to create simpler user experiences for citizens and frontline workers alike.

If you have a mess and automate it, you have an automated mess, so what is required is a rethink, and to achieve this requires leadership.

Change must be achieved step by step

Paul Hayes, policy manager at Wakefield Council, explains: “The big problem is when the technology is bolted onto existing systems. We need to rethink and repurpose, and challenge things we don’t need to do anymore.”

Orchestrating change, Mr Hayes says, needs to be done step by step. “A lot of the big change is coming about through communication, getting to know the user needs, so we see a lot of survey monkey use and social media interaction, for instance,” he says.

Such transformation demands investment and leadership at the highest levels, and the price of failure is likewise easy to see and grabs headlines. Global horror stories are easy to find, from the $2.1-billion US Affordable Care Act website debacle, to the UK’s National Health Service electronic health records disaster, which resulted in a £12.7-billion loss. These losses are not so much technological as thinking failures in a sector famous for being risk averse.

Public sector is slowly launching programme of digital transformation

Research conducted by iGov in 2017 evaluated progress of digital transformation in UK central and local government, concluding that a major “digital gap” still exists between how services are currently delivered and how they should be delivered in a modern, digital public sector, highlighting major barriers to overcome before an estimated £2 billion savings in online service delivery can be achieved.

After many delays, the UK government finally unveiled both its Government Transformation Strategy for 2017 to 2020 and its UK Digital Strategy to move pubic services into the digital economy. The announcement positioned the two strategies as a “means to restore trust in the way that government works with people, even in democracy itself” and to “create a digital economy that works for everyone”.

Translating this into reality will not be easily achieved, but Mr Hayes argues there is a fundamental principle to moving forward. He says: “Digital transformation aims to redesign and re-engineer government services, and this needs to be done from the ground up if we are to fulfil changing user needs.

“The problem is no one want to be first, they want to be second, to learn from somebody else. The public sector is risk averse, understandably so, because we’re messing with people’s lives if we take risks. It’s very much about social care, victims, vulnerable people.”

Good partnerships key to digital transformation of the public sector

Change can be triggered by partnering with private initiatives. Ben Howlett, managing director at Public Policy Projects, has been working on an impact assessment on new technology being introduced into the health service.

He says: “Instead of looking at the short, sharp fix of selling a product, the private sector could offer training and other relationship benefits to workers and patients alike. This means changing the way the public sector thinks, not just strategically but operationally, which will produce better outcomes, higher productivity and other benefits.”

A telling illustration is private sector providers offering medical apps. Babylon provides instant online contact with doctors for a £5 monthly fee, while VisitHealth offers on-demand healthcare by coming to patients wherever they may be with a sophisticated set of tools and tests, including ECGs and ultrasound.

Yulia Smal, VisitHealth chief executive, says: “We use our mobiles for immediate solutions, from ordering a cab to getting a spa service or a handyman. VisitHealth offers the same immediacy with healthcare answers, all without the anxiety that comes with turning to ‘Dr Google’ or getting only a fraction of the story in another phone or web-based service.”

Automation does not need to lead to loss of jobs

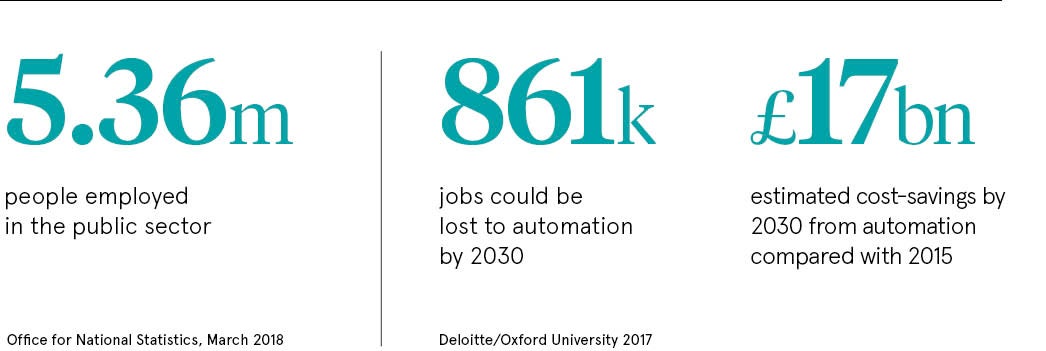

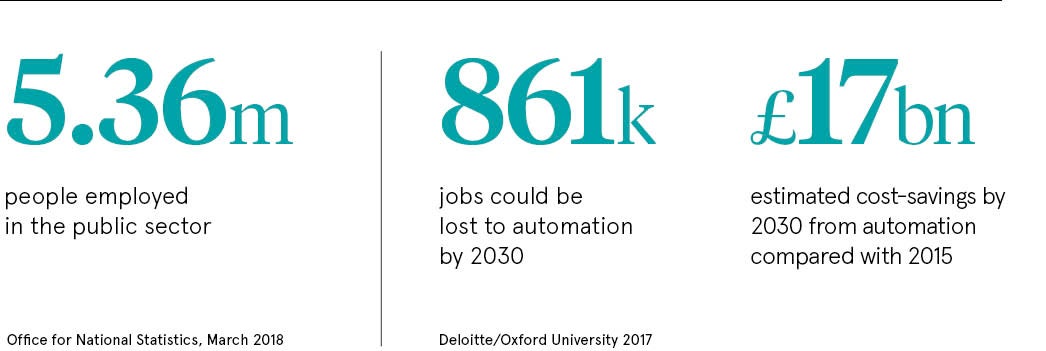

Apart from fear of failure and meeting user expectations, there is anxiety about the impact on public sector employment. Reform, a think tank dedicated to improving public service efficiency, calculates that almost 132,000 workers could be replaced by machines in the next ten to fifteen years, based on currently known automation methods.

Researchers suggest only 20 per cent of government employees do strategic, cognitive work that requires human thinking. Most of the rest are what Reform calls the “frozen middle”, levels of hierarchy where bureaucrats won’t act without approval from above.

Since 2013, Oxford University academics Carl Frey and Michael Osborne have been undertaking seminal work on automation risks for jobs, quoted by most other studies. In their 2016 report, in collaboration with Deloitte UK, they estimated about a quarter of public sector workers are employed in administrative and operative roles, which have a high probability of automation. They estimated some 861,000 such jobs could be eliminated by 2030, saving £17 billion for the taxpayer. These jobs would include Underground train operators, but mainly local government administrators.

If you have a mess and automate it you have an automated mess, so what is required is a rethink

Mike Turley, global head of public sector at Deloitte, explains: “The public sector has a high number of public-facing roles, particularly those in areas such as education and caring. These will be relatively safe from automation and could see the public sector impacted less than other sectors. However, automation still has significant potential to support cost-reduction, meet citizens’ expectations of public services, free up real estate, save staff time and improve productivity.”

Ever since the Luddites, in the early-19th century, fear of job losses has been a commonplace reaction to automation, but it can work positively. Mr Howlett concludes with the example of two people who have been making plaster molds in facial reconstructive surgery for the past 30 years. “They can now be retrained to use 3D printers to make measurements,” he says. “They make more accurate measurements, save time and can do the 3D printing themselves, using that experience and training for succession planning. They keep their jobs, but the job is different.”

Change must be achieved step by step

Public sector is slowly launching programme of digital transformation