When Sir Kenneth Olisa became the first British-born black man to be appointed director of a FTSE 100 company, he recognised he was a pioneer.

But it didn’t strike him as a bold move on the part of the business, Reuters media group, but rather it stemmed from a desire to gain a competitive advantage.

“Reuters was a progressive business and, as a media and information group, the focus was on facts rather than prejudice,” he explains. “I am pleased to be a pioneer for diversity in leadership because it makes people think.”

That was in 2004 and progress since has been painfully slow. Although McKinsey’s Delivering through Diversity report found companies that lead in ethnic and cultural diversity on executive teams are 33 per cent more likely to enjoy industry-leading profitability, there remains a lack of diversity in leadership at most organisations.

Why are so many companies falling short?

“A lot of companies recruit in their own image, but an organisation which reflects its customers and supply chain will be more competitive,” Sir Kenneth points out. “There has to be a recognition of the competitive advantage of diverse leadership, rather than the social-justice argument.”

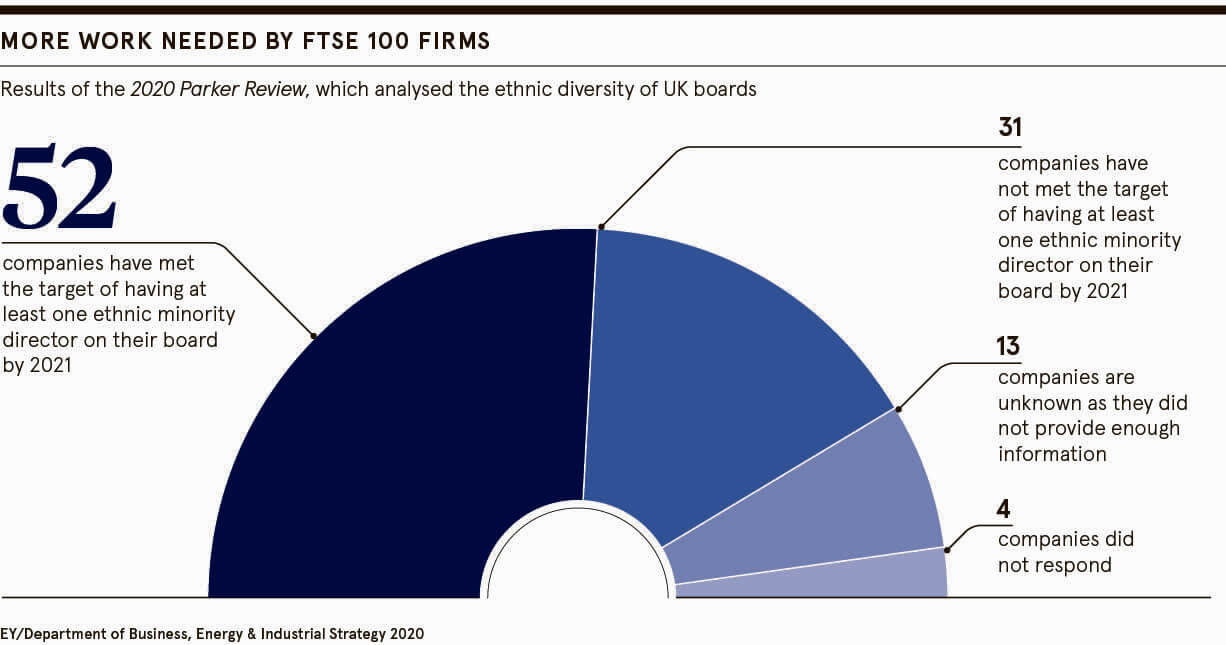

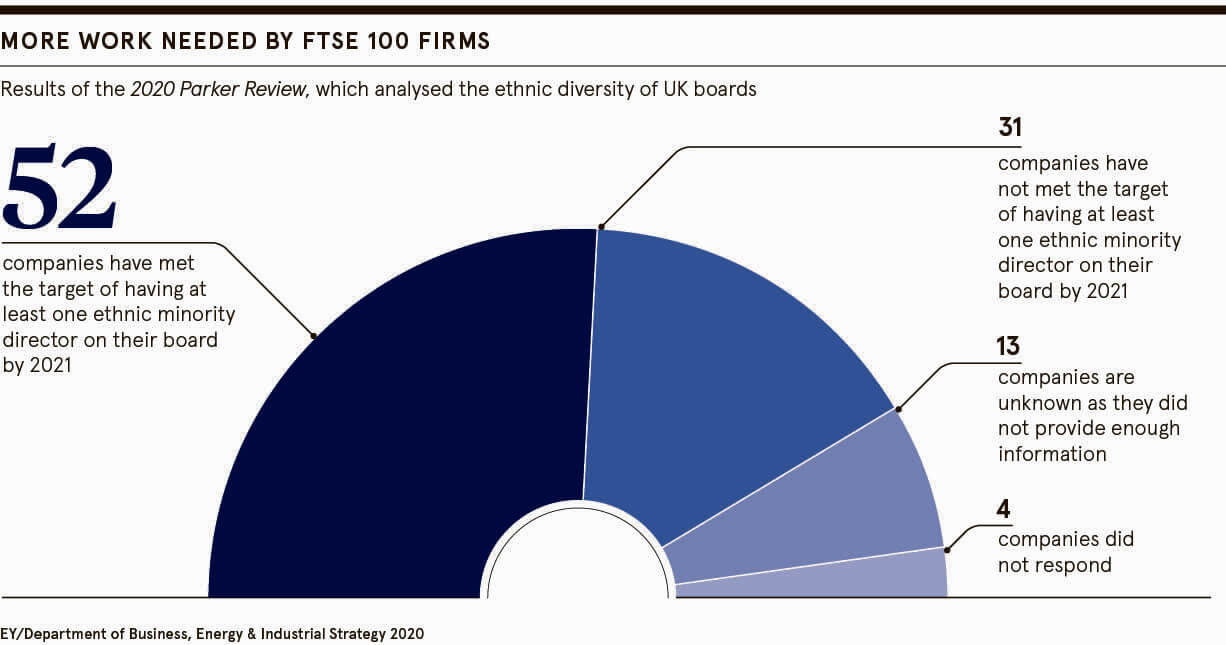

The latest update from the government-backed Parker Review, found the majority of companies are falling short. The target for FTSE 100 companies is to have one non-white director by 2021, with another three years for FTSE 250 businesses to achieve that goal. Currently 59 per cent of companies are not meeting the target.

The review’s chair, Sir John Parker, acknowledges the task. “Our continuing lack of ethnic diversity looks less like a failure on the part of minority communities to produce competent candidates and far more like a choice on the part of business to settle for familiar recruitment processes,” he says.

There has to be a recognition of the competitive advantage of diverse leadership, rather than the social-justice argument

In a parallel drive, sustained focus on increasing gender diversity in leadership has made progress. Latest figures from the government-backed Hampton-Alexander Review show women now hold a third of board positions among FTSE 350 companies, after targets originally set in 2015, although they still fall short in executive roles.

This shift can be replicated with ethnic diversity, says Dr Doyin Atewologun, director of Cranfield School of Management’s Gender, Leadership and Inclusion Centre.

“It’s completely understandable from a social and psychological point that we don’t have the same fluency with ethnicity as we do with gender,” says Atewologun. “But the first practical step is acknowledging that and doing something about it.”

Need to challenge the meritocracy myth

Talking about the issue in the business, increasing personal knowledge and holding executive search firms more accountable are key, she says.

There are already executive search firms dedicated to placing director-level people of colour, such as Green Park, which operate on the philosophy there are qualified diverse candidates for every position.

For Atewologun, the main challenge is changing the narrative around the “meritocracy myth”. She argues: “For some there’s the suggestion that by considering greater diversity in leadership there would be a question around merit.

“We need to challenge that discourse. When organisations link meritocracy to diversity they are perpetuating bias in a story that hundreds of thousands of shareholders are reading, which suggests it is questionable.

“This is the paradox: if you take a sample of black and minority ethnic [BME] leaders or women leaders for example, they will have a list of achievements as long as your arm, because they have spent so long working to be better.”

How tech can improve diversity in leadership

Technology could help, using data to identify potential candidates not necessarily within a board or executive search company’s networks. This could be critical for change, although there is a need to be wary of embedding existing biases into artificial intelligence (AI) environments, says Professor Chris Rowley, human resource management specialist at Kellogg College, University of Oxford, and Cass Business School, City, University of London.

“Corporate cultures are embedded in societal cultures, as well as ethnocentricity and stereotyping, and are notoriously different to change,” says Rowley.

“Using new technologies such as machine-learning and AI could reduce well-known explicit and implicit bias in recruitment processes, although the other side is who actually sets the algorithms?”

However, research shows 87 per cent of HR leaders are not aware or don’t use any technology specifically designed for improving diversity in the workplace.

What concrete steps are actually being taken?

But organisations are making progress, with measurement recognised as essential for meaningful change in the UK, where at least 13 per cent of the population is from a BME group.

Lloyds Banking Group has set goals to increase diversity in leadership, including its commitment to 8 per cent BME representation in senior management by the end of 2020. As of 2019, Lloyds had reached 6.7 per cent BME representation in senior management.

Fiona Cannon, the banking group’s responsible business, sustainability and inclusion director, explains: “Having a public goal has been the single most transformative action we have taken. It means we’re genuinely treating diversity in the same way as any other business issue and we believe what gets measured gets done.”

Lloyds is focused on “removing barriers which stop any colleague succeeding on merit”. “As a result we’ll have more diversity in shortlists for senior roles,” she says.

Insurance provider Hiscox has a strategy that includes a senior sponsor on its executive committee, a head of diversity and inclusion (D&I), and a board diversity statement to ensure executive and non-exec directors are accountable. It also launched an employee network programme, including LGBTQIA+ and pan-African networks.

Head of recruitment at Hiscox Vanessa Newbury concedes that the “war for talent at middle management and above is fierce across the industry”.

“Our approach is long-term investment,” explains Newbury. “This means nurturing talent we have in-house and ensuring D&I forms part of our succession planning and talent mapping. Our efforts are geared towards levelling the playing field where everyone has the chance to thrive.”

Change is happening, but these elements must combine to propel progress in recognising talent in the business community that reflects the wider population to amplify diversity in leadership.

Why are so many companies falling short?

Need to challenge the meritocracy myth

How tech can improve diversity in leadership