What’s in a name? Shakespeare’s enduring question from Romeo and Juliet still holds meaning more than 400 years after the play was written, as name bias continues to be a barrier for employees.

In 2015, then-prime minister David Cameron addressed the issue, albeit less poetically, at the Conservative party conference. He said: “Do you know that in our country today, even if they have exactly the same qualifications, people with white-sounding names are nearly twice as likely to get call-backs for jobs than people with ethnic-sounding names?”

Nearly five years later, the job market has certainly become more complicated thanks to the issues and uncertainties around Brexit, business and the future, and this can arguably contribute to unconscious bias being an increasing issue in the workplace.

Study reveals CV name bias is rife

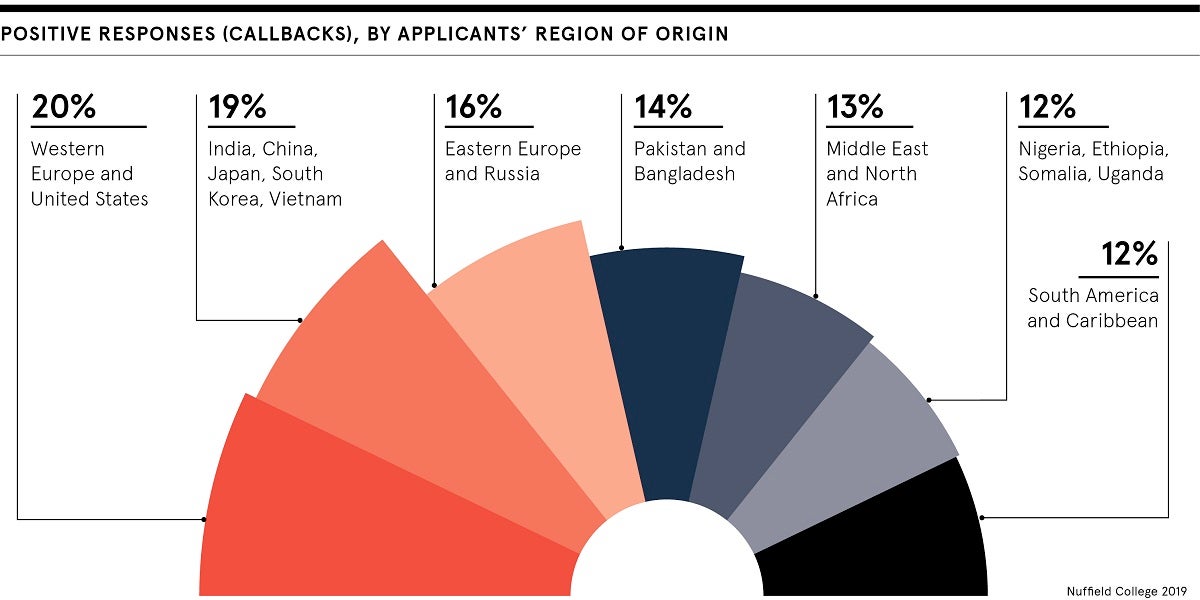

A study launched by the British Academy at the beginning of the year revealed that on average 24 per cent of applicants of white British origin received a positive response from employers. Only 15 per cent of minority ethnic applicants, who applied with identical CVs and covering letters, received positive responses.

Concerns about English language fluency or education levels can’t be raised in these cases as all applicants stated clearly in their CVs that they were either British born or had lived in the country since the age of six and had a British education.

Minority ethnic applicants and white applicants with non-English names have to send on average 60 per cent more applications to get a positive response from an employer than a white person of British origin.

People of Pakistani origin had to make 70 per cent more applications, while candidates of Nigerian and Middle Eastern or North African origin had to send 80 and 90 per cent more applications respectively.

This isn’t simply a question of political correctness, it’s a matter of law. The Equality Act says employers who discriminate on grounds of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage or civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation are breaking the law, and are opening themselves up to potential prosecution. This is the real reason why there has been a widespread concerted effort from big organisations to put managers through training to counter unconscious bias.

But this alone isn’t going to change the culture and attitudes which led, in 2016, to the Confederation of British Industry recommending the removal of candidates’ names from job applications so employers would only focus on the skills and experience of applicants.

Specific roles lead to higher levels of bias

Many agencies representing candidates will take the names off applications when putting them forward for jobs. Holly Olugosi is a talent and training partner the The One Group, a recruitment agency based in Cambridge, and previously ran their finance desk, putting forward prospective candidates to clients in the finance world. She has seen first hand how name bias has held back qualified candidates from being called for interview.

Small and medium-sized enterprises are more likely to be reluctant to interview candidates with foreign names

“It is certainly more noticeable when recruiting for client-facing staff, receptionists or customer service people,” she says. “Small and medium-sized enterprises, especially family-run businesses outside London where there is less cultural diversity, are also more likely to be reluctant to interview candidates with foreign names.”

Ms Olugosi used her maiden name, Chapman, when working in a client-facing position. “If I have to cold call a client and they ask me what my name is, I have to go through the whole thing of spelling and pronunciation,” she explains. “I don’t care if they spell it right, but they can feel a bit awkward, so I just used Chapman and only started using the name Olugosi when I was no longer client facing.”

Business consultant Julia Bernard-Thompson also found her name would lead to some difficult interactions. Although she is Trinidadian, her name would often lead some people to assume she was white, an assumption they would often not be able to hide. “People have said ‘you don’t look like a Julia Bernard-Thompson’ to me,” she says. “But they would struggle to explain what they meant by that when I asked them.”

Name-blind recruitment the way forward

Ms Bernard-Thompson has spent a lot of time researching name bias and recently did a Tedx talk on the impact of names. She found that while in most cases, minority applicants would be more likely to be discriminated against, there were some examples where the reverse was true. “There’s evidence to suggest that bias works in favour of some minorities when it comes to tech,” she says. “Asian names get priority often because of the stereotypes that people have about these groups of people.”

As far as she is concerned, name-blind recruitment is the way forward. “It’s one of the easiest ways of giving people genuine access to opportunities. They get to make a fair representation of themselves in the interview, based on their skillset and the opportunity,” says Ms Bernard-Thompson.

And it does seem to be becoming the norm. When Mr Cameron announced in 2015 he would be introducing blind recruitment to the civil service, HSBC, Deloitte and the BBC followed suit. After all, assumptions and opinions will always be made on whatever information people have to hand.

Ms Bernard-Thompson speaks in her Tedx talk about how Barack Obama was known as Barry Sotoro before college, a Westernised abbreviation of his first name and his step-father’s surname. Bill Clinton uses his step-father’s name and his legal name is William, and Tony Blair’s full name is actually Anthony Charles Lynton Blair.

Did these changes impact on the positions these individuals found themselves in further along in their careers? It’s hard to tell, but before we start asking what’s in a name, surely the focus should simply be what are the skills and experience on this person’s CV?