In 1913 aspiring lawyer Gwyneth Bebb, along with three others, sought a declaration that she was a “person” within the meaning of the Solicitors Act 1843 and therefore entitled to take the Law Society’s exams to qualify as a solicitor. While Ms Bebb et al failed, their claim provided momentum for the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, which enabled women to become lawyers.

Almost one hundred years since the act, progress has been made along the road to equality, but more needs to be done. Baroness Hale made history last year becoming the first female president of the Supreme Court. Lady Black joined her as the second woman to sit on the country’s highest court and, for 11 brief months until July, the position of justice secretary and lord chancellor was held by woman, Elizabeth Truss, albeit not a lawyer.

The number of women (47 per cent) entering the legal profession is almost level with the number of men and that looks set to rise, as UCAS figures show that last year for the first time, the number of women (17,565 or 67 per cent) who accepted a place to study law at university was more than double the number of men (8,510 or 33 per cent).

The reasons used to keep women out are the same as in 1917 and are based on the same sexist stereotypes

Dana Denis-Smith, founder of the First 100 Years Project, which is creating a digital archive charting the history of women in the legal profession, says: “Women have come from nowhere – from a point where they were barred from the profession, to making up an almost 50:50 ratio of those entering law – in 100 years. They have advanced.”

But, she adds: “The debate has not evolved. The reasons used to keep women out are the same as in 1917 and are based on the same sexist stereotypes.”

While there is equality at entry level, further up the pecking order high attrition rates, due variously to career breaks, the failure of men to value what women bring to the table and the promotion structure within law firms, the picture is more skewed, says Leah Glover, chair of the Law Society’s Women Lawyers Division.

Figures from the Solicitors Regulation Authority show that women make up only 33 per cent of partners in law firms. Despite a number of major law firms signing up to The 30% Club, committing to a 30 per cent female partnership by 2020, the latest promotion rounds indicate that the number of women making it to partner at the UK’s largest law firms has fallen by almost a quarter over the past two years.

A report from BPP University Law School, Law Firm of the Future, which analysed more than a quarter of a century of Law Society data, suggests it will take another 20 years to get gender parity in senior positions.

Among the 16,500 barristers, figures paint a similar picture. Data from the bar’s regulator, the Bar Standards Board, shows that although 51 per cent of pupils are female, women make up 37 per cent of the practising bar, a figure that many fear will drop due to government plans to pilot extended sitting hours in criminal courts.

At the top of the bar, only 13.7 per cent of Queen’s Counsel are women and, predicts the BSB report, at the current rate of change, it will take more than 50 years to reach gender parity. Although, 32 (27 per cent) of the 119 QCs announced in December are women, giving hope that the BSB’s prediction is perhaps pessimistic.

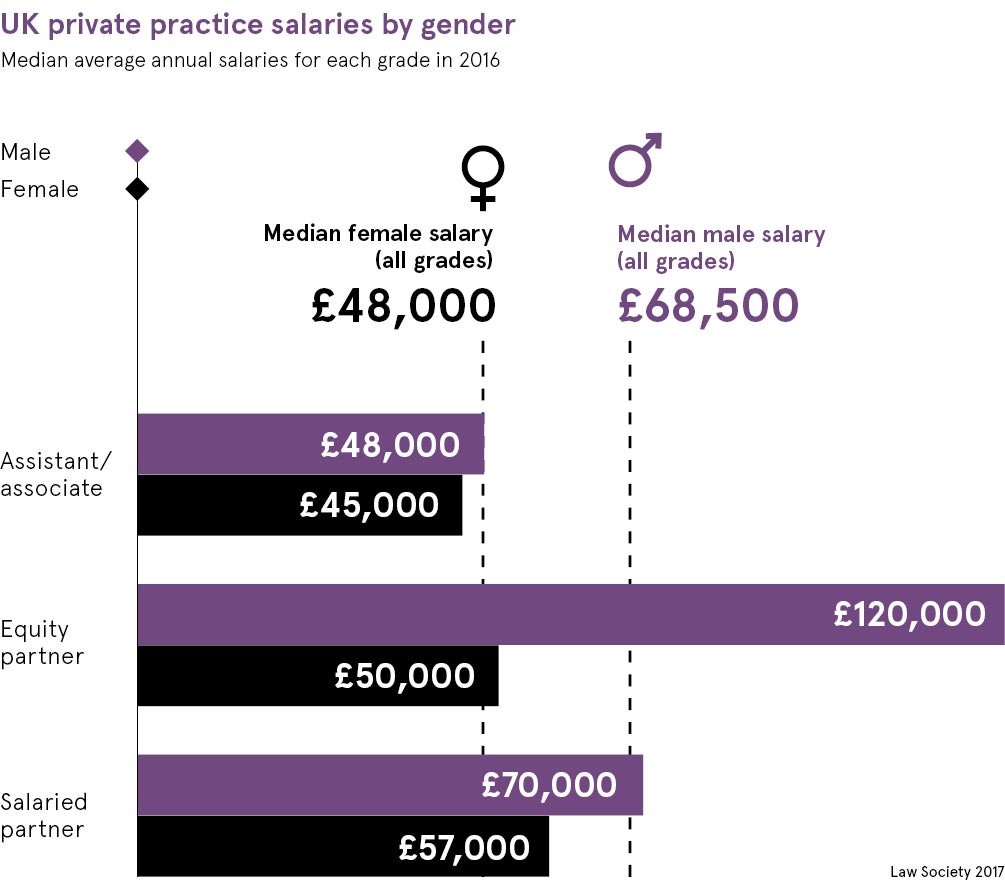

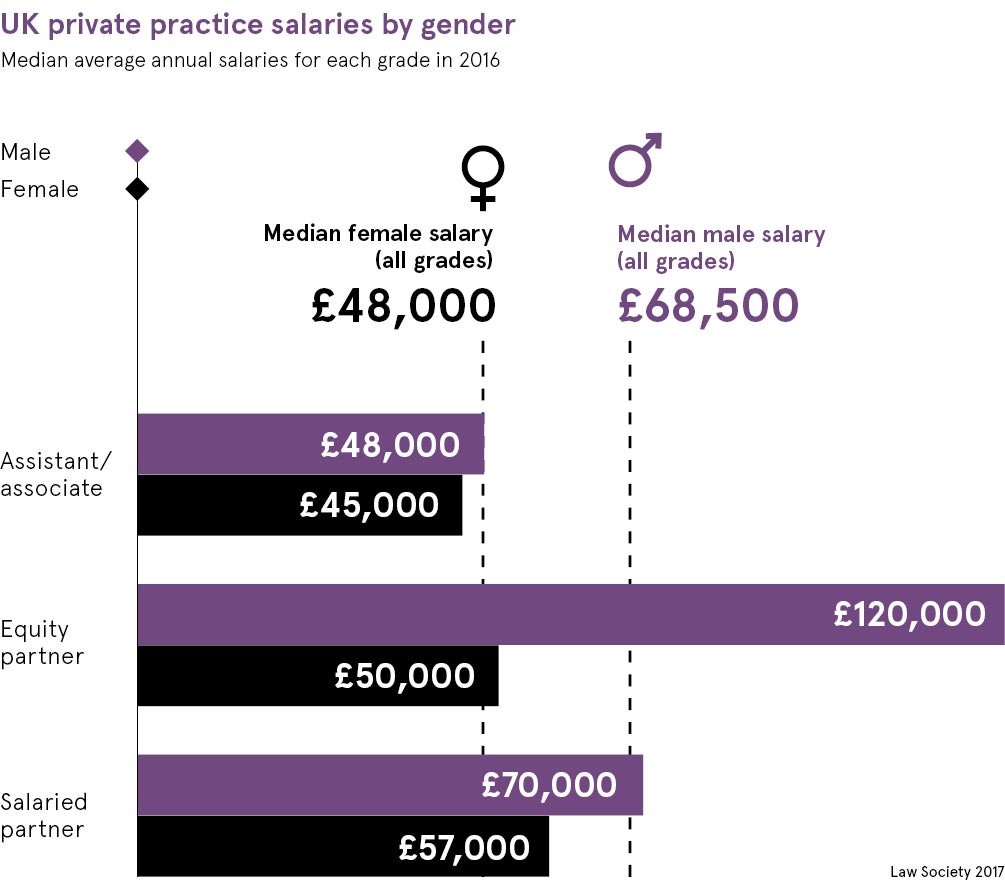

Women in law, as in most other professions, are paid less than their male counterparts. According to the Law Society, the gender pay gap across all private practice solicitors in England stood at 30 per cent in 2014. But the Office for National Statistics suggests that women in the legal profession are paid 10.3 per cent less than their male colleagues, a smaller gap than the 18 per cent national average.

A more accurate picture will emerge thanks to the Equality Act 2010 (Gender Pay Gap Information) Regulations 2017, which requires bodies with more than 250 employees to publish gender pay gap figures every year from April. So far, three large law firms have published theirs.

International firm Herbert Smith Freehills’ figures show that it pays its female staff almost 20 per cent less than the men and gives them 30 per cent smaller bonuses. Women at City firm CMS are paid 17 per cent less than its men and get bonuses that are about 27 per cent smaller, and at regional firm Shoosmiths, women are paid 15.5 per cent less.

The make-up of the profession determines the pool from which judges are drawn. Since 2010 the proportion of women judges in courts has gone up by a third. The latest statistics, from April 2017, show that 28 per cent (890) of judges are women. Among the most senior, two of the 12 Supreme Court justices, nine (24%) out of 38 Court of Appeal judges and 21 (22 per cent) out of 97 High Court judges are female.

The judiciary appears to take seriously the desire to increase diversity, setting up the Judicial Diversity Committee, chaired by Lady Hallett. It organises networking, work shadowing and mentoring events, and support programmes to encourage under-represented groups to apply for judicial appointment, and has put together online videos and personal case studies.

QC Appointments, the body charged with administering the process for silks, has also taken measures to ensure there are no barriers for women. Its chief executive Russell Wallman explains that it has reduced from twelve to eight the number of judicial assessors applicants are expected to list and increased the time period over which their supporting cases are selected from two to three years. When women do apply for silk, Mr Wallman notes that they are more successful than man, but they are still applying in smaller numbers.

In the wider profession, the Bar Council and Law Society, as well as law firms and chambers, are implementing initiatives to redress the gender imbalance, including maternity and returning-to-work schemes to help with applying for silk or judicial appointments.