While researchers, notably Myers-Briggs, indicate that around half the global population are introverted, a new study suggests introverts in the workplace may become victims of unconscious bias.

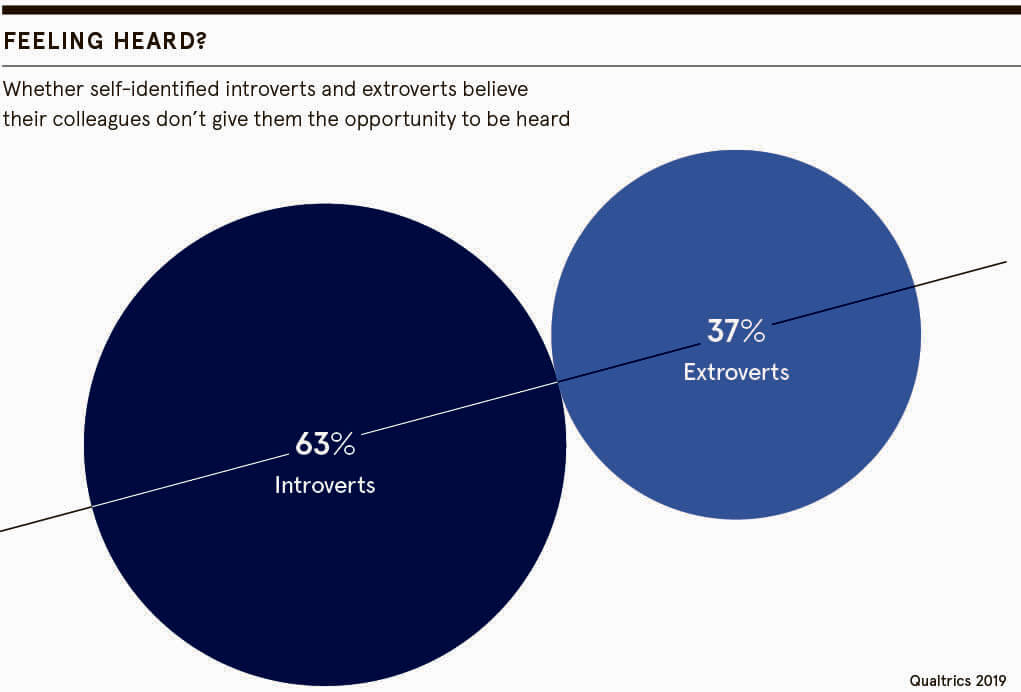

The Silent Worker report, by experience management software provider Qualtrics, reveals that just under two thirds of the 1,000 UK workers it questioned, who identified as introverts, believed they were not given the chance to be heard. Just over half also felt their opinions were neither valued nor listened to.

Joanna Rawbone, founder of consultancy Flourishing Introverts, is not surprised by such findings, describing this area of neurodiversity as “one of the most overlooked in diversity and inclusion terms”.

“Some employers are becoming more aware of the situation, which is important because it’s potentially having an impact on huge numbers of staff,” she says. “But while they may know the difference between an extrovert and an introvert personality, it’s not generally on the agenda to do anything about.”

There has long been a societal bias towards extroverts in Western cultures, says Amy Walters, senior research consultant at management consultancy Lane4. Another challenge is the terms “extrovert” and “confidence” tend to be used interchangeably, even though extroversion and introversion, in Jungian analysis, refer to where individuals derive their energy.

In other words, while extroverts recharge their batteries from mixing with others and generally prefer to think and plan in group settings, being an introvert in the workplace means being more inward-facing and happier undertaking such activities alone.

Pros and cons of introverts and extroverts

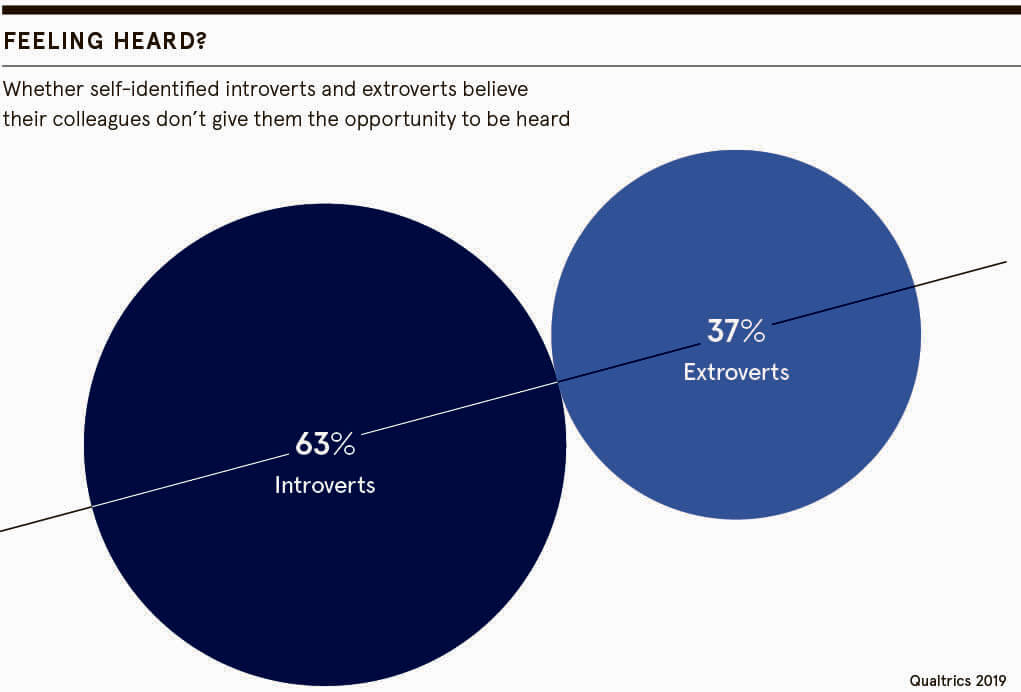

As a result, common extrovert strengths include responding quickly to ideas and inspiring others, while potential weaknesses include a tendency towards knee-jerk reactions and dominating conversations.

Positive introvert traits, on the other hand, include being good listeners and thinking things through, while possible downsides include taking longer to make decisions and being perceived as more difficult to talk to.

“Anecdotally, managers, particularly if they are extrovert themselves, see other extroverts as being easier to work with,” says Rawbone. “They class introverts as difficult and shy, and feel extroverts are more fun and easier to talk to, so they tend to be picked for projects or are given opportunities introverts aren’t.”

Indeed, academic research has shown this kind of unconscious bias means “individuals who are higher in extroversion are more likely to be selected and promoted into leadership positions”, Walters points out.

Although many introverts in the workplace push themselves to conform by trying to appear more outgoing than they actually are, the problem is that doing so over a prolonged period results in people no longer being authentic or true to themselves, which can in turn lead to overwhelming stress and eventually burnout.

So, what can employers do to address this largely unacknowledged situation and ensure the complementary strengths of both extrovert and introvert personalities are valued and rewarded equally?

Creating an inclusive culture

According to Rawbone, there are three key steps. The first involves doing a “stocktake” to understand where unconscious bias is taking place and what the organisation’s standard behaviour towards introverts is.

The second entails consciously changing this behaviour to promote the inclusion of all personality types. This involves, thirdly, introducing education and training programmes not only for managers, but often also for the wider team. Encouraging the development of group facilitation skills to optimise team and meeting dynamics is an example.

As Natasha Wallace, founder of leadership development consultancy Conscious Works, explains: “Managers need to make it safe to speak up, encouraging everyone to contribute. If people don’t want to express their ideas in a group setting, managers should be picking up with them afterwards to get their thoughts.”

Another useful tactic in this context is to send everyone an agenda in advance, thereby giving introverts time to think through the issues beforehand to help them feel more comfortable in contributing.

The final stage, meanwhile, is about embedding change in the workplace. Possibilities range from creating quiet spaces so introverts can take time out, to ensuring line managers conduct regular check-ins with their staff to boost general trust and wellbeing.

As Rawbone concludes: “Good management is about understanding all the members of your team, helping them to play to their strengths and creating an environment in which they feel included, valued and self-motivated.”

Pros and cons of introverts and extroverts