From smart devices such as home hubs, which automate lighting, to retail software which minimise food waste, technology using the internet of things (IoT) is fast becoming a driving force in innovation. Yet while the sales of smart speakers, such as Amazon Echo and Google Home are booming, many companies are still experimenting with ways to monetise IoT.

While companies including Phillips and Audi were early adopters of the new technology, the global IoT market has been marked by the reluctance of consumers to switch from dumb devices.

But this is set to change as a reduction in the cost of new products will see a major boost in consumer confidence over the next five years. The worldwide IoT hardware market for the retail sector, which totalled £616 million in 2015, is set to quadruple to £2.5 billion by 2020. Juniper Research predicts the number of connected IoT devices, sensors and actuators will see an increase of 200 per cent from 2016 levels to 46 billion in 2021.

Traditional business models will gain traction in the medium term, while more exotic or bespoke solutions will emerge later

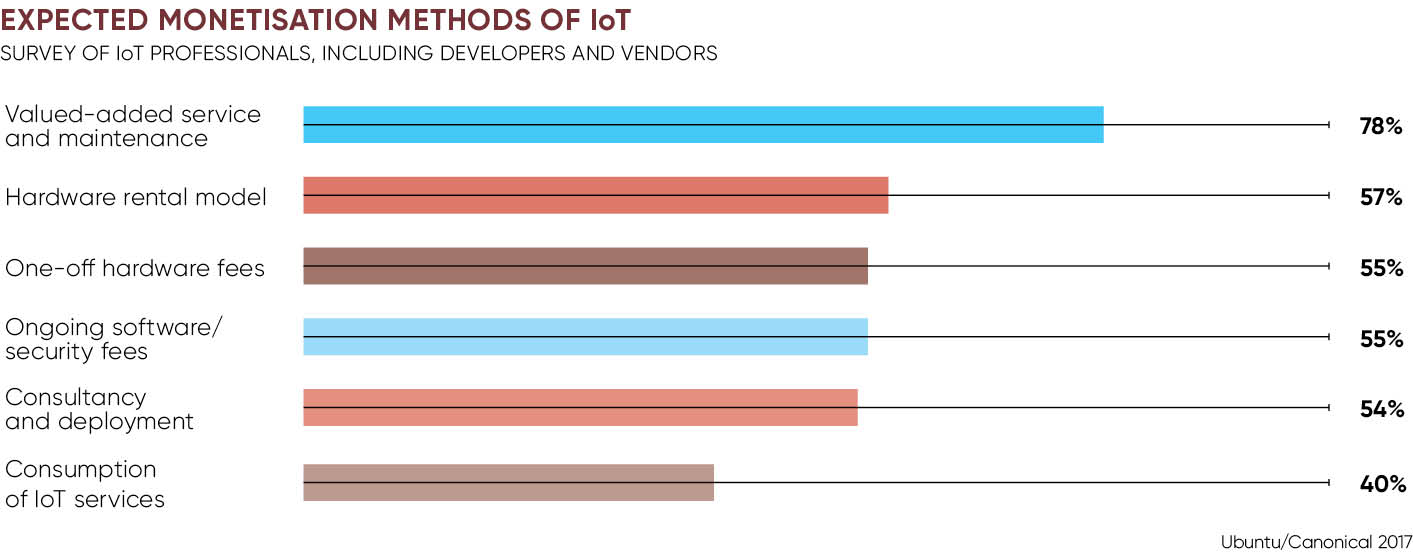

“I think the monetisation of IoT is critical,” says Daniel Young, managing director of Eridanis, an IoT consultancy with offices in London, Paris, Montreal and Singapore. Eridanis helps businesses adopt emerging technologies. In its 2017 report Examining IoT Business Models, Eridanis says traditional business models will gain traction in the medium term, while more exotic or bespoke solutions will emerge later.

“For IoT to be profitable, money needs to be ploughed back into research,” says Mr Young. “The cyber and physical solutions that make up these systems are expensive at the start. A hardware solution is expensive and requires investment. Many IoT companies initially thought everyone would want a smart thermostat and then they realised it is quite expensive to make this hardware.”

While IoT devices such as smart lights have been available for several years, customers often cite cost as a major obstacle in switching over from current devices. A basic wireless lighting starter kit for an average home can cost around £200. There are also related issues for manufacturers of traditional unconnected devices as smart technology is labour intensive to research and expensive to develop. Another drawback is that customers are reluctant to acquire expensive devices which need to be repaired or maintained by monthly subscription fees.

For large companies that sell to governments or local authorities, IoT technology can often fit into a traditional supply-and-demand model. “Our model reflects the way street lighting is funded,” says Keith Day, vice president of marketing at Telensa, a world leader in connected street lighting. Telensa has its headquarters in Cambridge and manufactures its smart lights in Wales. The company has annual revenue of around $23 million and has installed 80 street lighting networks around the world, totalling 1.5 million street lights.

“Typically, the capital investment for street light replacement project comes from some form of government funding,” says Mr Day. “Any authority or PFI [private finance initiative] contractor would need to fund the capital outlay.”

While Telensa’s business model relies on governments and local authorities purchasing sizeable numbers of lights and controls, future applications of IoT may require authorities or consumers to sign monthly subscriptions.

“In the future and with other applications, such as smart waste, we would expect there to be a monthly subscription model,” says Mr Day. “Our business model, in terms of why you might want to invest in smart street lighting is to do with the benefit from energy-savings beyond what you get from switching to LEDS.”

A number of IoT companies are using different models to charge for services. London-based Winnow helps restaurants and catering businesses reduce food wastage by up to 50 per cent. Kitchen staff use an app to log every discarded item, including leftovers and peelings. A set of smart scales and a tablet records food types and products; the resulting data is uploaded to the cloud, analysed by an algorithm and distributed to chefs and managers.

Winnow charges restaurants and caterers a subscription fee for their software that weighs and logs discarded waste to save on annual food costs

Winnow charges businesses according to a sliding scale of around $2,000 a year for a small restaurant, to tens of thousands of dollars for cruise ships with multiple catering sites. Customers typically save around 8 per cent on their annual food costs.

Launched in 2013, Winnow currently saves its customers around $10 million a year in food costs. The company operates in 1,000 kitchens in 30 countries. Clients include IKEA, AccorHotels, Pizza Hut in the UK, and catering services run by Compass Group UK and Ireland – the UK’s largest food services firm – at the University of Sussex and the Wellcome Trust. Winnow recently announced it had raised $7.4 million in additional funding.

“Our revenue model is a recurring fee which we charge clients for software and hardware,” says Winnow founder Marc Zornes. “Kitchens are relatively challenging places to work in, so we provide a full-service model. The software was developed in house. We also developed the scales, which are proprietary. Kitchens are noisy environments. We have hardware which has firmware on it – it ignores things like the scale being kicked. We identify and procure the right equipment for the kind of kitchen it will be used in.”

Monetising IoT is a challenge often common with startups, according to Matt Webb, managing director of R/GA IoT Venture Studio UK, which recently launched its second programme to help early and growth-stage companies working in IoT. “With IoT companies, we see the same kind of skills and challenges often seen at startups,” he says.