For as long as there have been robots, there have been fears they will take people’s jobs. The rise of the internet of things (IoT) echoes these concerns. An engineer no longer has to monitor a machine or switch on a bank of lights, IoT sensors can do it instead. Smart devices may not be an answer to the global talent shortage, but they’re starting to impact the work employees do.

The likes of heating, lighting and maintenance are already being automated, reducing routine tasks and eliminating others, in offices and factories around the globe. Demand for IoT is changing the role of facilities managers in a way that mirrors how self-service checkouts disrupted customer services in supermarkets or automatic doors and monitoring systems have affected guards and train drivers.

“The increased deployment of data-driven technologies is raising social, legal and ethical questions about the impact on people and their everyday lives. It’s vital that we find ways to engage with employees and the public, as well as identify the issues so they can be addressed,” says Julian David, chief executive of techUK.

Thought leaders are keen to highlight the strong demand for IoT isn’t going to lead to mass redundancies or answer post-Brexit talent shortages, an ageing demographic or lead to less work for humans. Instead the focus is on IoT helping people do jobs better, with more productive and added-value tasks, empowered by data, redefining employment in the process.

“It’s about giving people more time to use their expertise where it is more critically needed. With predictive maintenance, teams work in new, more impactful and proactive ways rather than reactively dealing with disruptions, which means this also minimises employee stress,” says Belen Moscoso del Prado, group chief digital and innovation officer at Sodexo.

Lack of IoT skilled workers

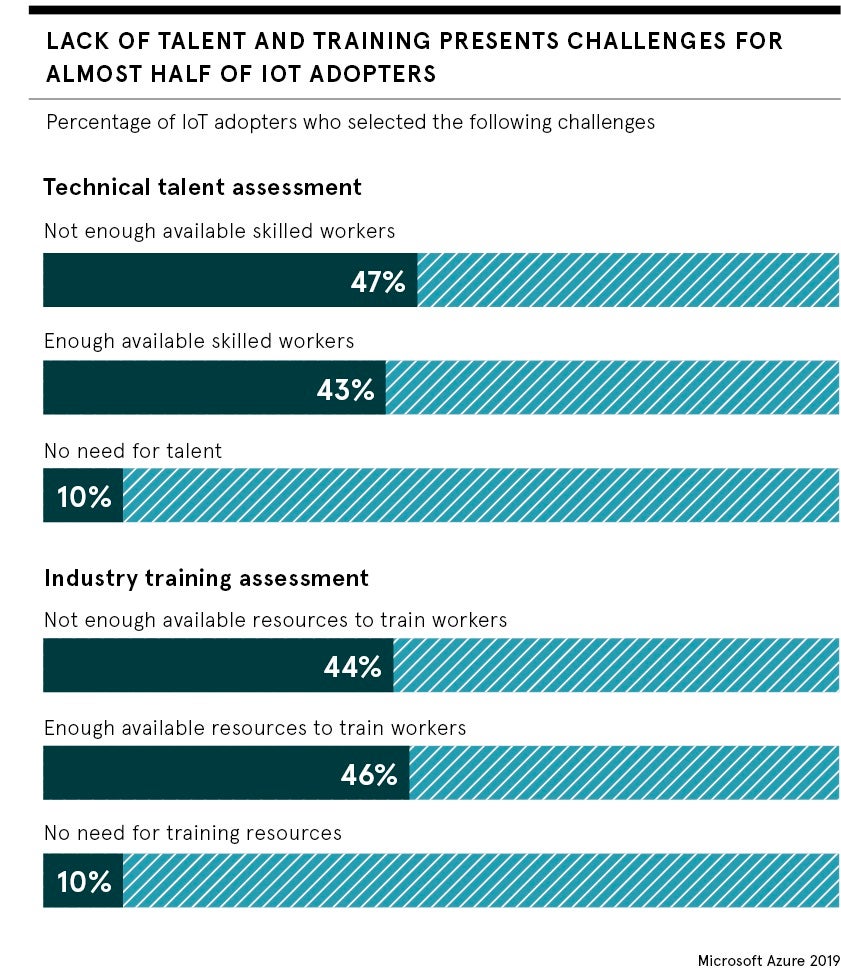

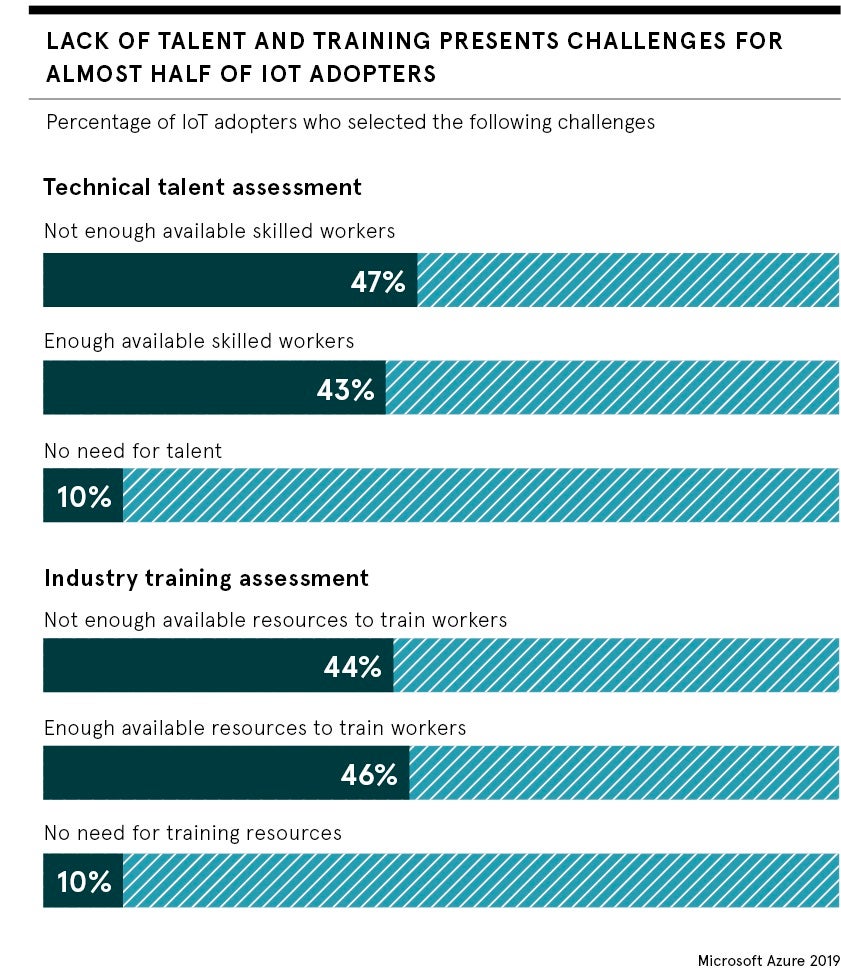

Ironically there is less worry about job losses with the rise of IoT and more concern over talent shortages, as well as how to fill new roles created by its increasing deployment. IoT networks need new levels of expertise focused on data analytics and data science, but knowledge is thin on the ground.

“IoT requires a set of information and operational technology skills that are often hard to find in combination. Businesses face a skills shortage, particularly in digital engineering capabilities, and are hindered by a fragmented skills system and a lack of systematic engagement between education and industry,” says Pat Nash, managing director of InVMA.

Innovation in IoT has focused on areas where machine-learning easily beats humans, these are the tasks that are first to digitalise, and in the process retraining and filling the skills gap becomes crucial.

“There will be a reshuffling of the tasks that we typically do and ones we will do differently because we interact with machines,” explains Ernst Ekkehard, chief macroeconomist at the International Labour Organization. “The risk we currently face is that many jobs across different sectors are changing quickly and simultaneously; anticipating such changes is not an easy task.”

This is also because organisations are now deploying a “smart ecosystem” approach. The key to success is not confining demand for IoT to one part of the business, but doing it at scale and selectively where it makes the most difference; this also has implications for the workforce.

“IoT is not a fire extinguisher and should not be applied to solve everything, but used to enhance, add value and improve the workplace. It should ultimately bring more benefits to workers, not eliminate them,” says Johan Carstens, private sector chief technology officer at Fujitsu.

Combatting to fight the talent shortage

Those deploying IoT solutions talk of empowering employees, not disempowering them, allowing workers to do more, not less, upskill not deskill. On the employee side, absorbing all this change in the workplace is a big issue. “It will become increasingly challenging to stay relevant,” says Thomas Frey, futurist and executive director of the DaVinci Institute.

When it comes to talent shortages, the good news is IoT plays to the strengths of a new cohort entering the workforce, Generation Z and beyond. “They grew up alongside technology and expect it in their work. From Minecraft to Instagram, they know how to use data in evermore creative ways to add value,” says Jonathan Bridges, chief innovation officer at Exponential-e.

Such creativity could in turn be used to focus IoT sensors on employee activity, defining a worker’s every move and how they operate. Companies are now increasingly using IoT to gather data about workforce movements, often anonymised in this post-General Data Protection Regulation world. For instance, facilities managers are sent text messages if they don’t turn off lights or machines.

Many jobs across different sectors are changing quickly and simultaneously

“Some monitoring has serious ‘big brother’ associations, invading privacy and creating stressful working environments. Given the importance of data to machine-learning, there’s intense scrutiny of the legal basis for the control of data and whether the law should change,” says Matt Hervey, head of artificial intelligence at Gowling WLG. “The law does not cater well for the ownership of most data. Employees do not own data collected about them, but have rights affecting the data.”

Certainly, without proper communication, scrutiny and education on the benefits of IoT, mistrust could grow. “There could be a backlash, especially if there are unions involved. It’s really important to bring everyone along with this journey,” Mike Jeffs, chief commercial officer at Hark, concludes. Maybe it’s time to start having that conversation right now.

Lack of IoT skilled workers